Introduction

This article on “Modernist painters and illusory pictorial space” was written in response to Posts Page comments by Ken Marunowski (see comments section of Chapter 10 : Illusory pictorial space and light)

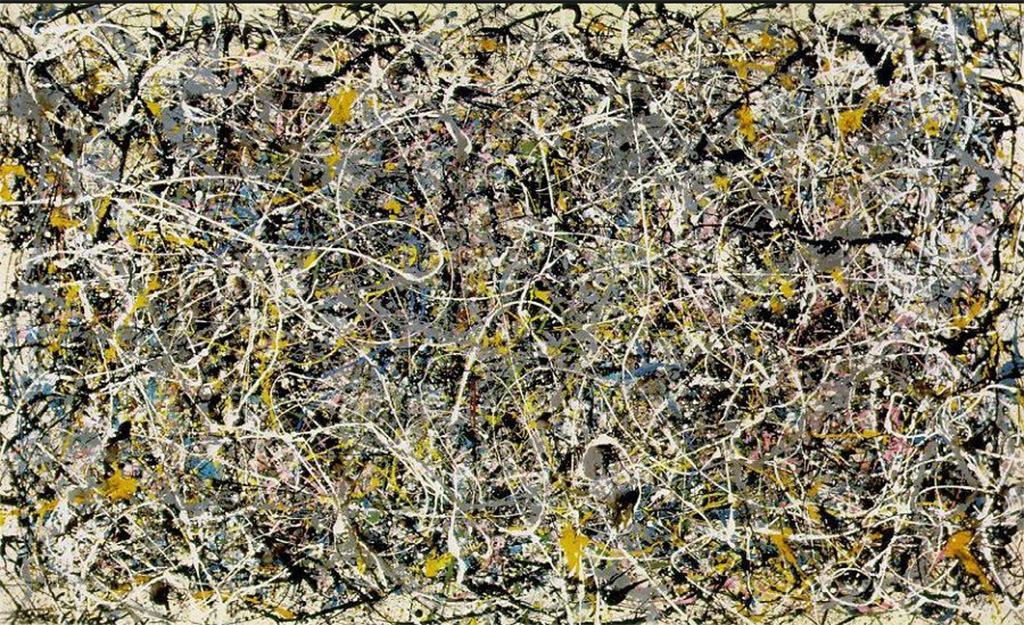

Clement Greenberg, Jackson Pollock and a space within the picture surface

Clement Greenberg was a high profile mid twentieth century art critic whose thoughts on Modernism in Painting influenced a generation of artists. He had much to say on the paintings of Jackson Pollock to which he accorded a special importance. One of the reasons why was that he saw in them an unprecedented type of “pictorial space”. This he called “a space within the picture surface”

.

.

A moralistic reaction against photographs

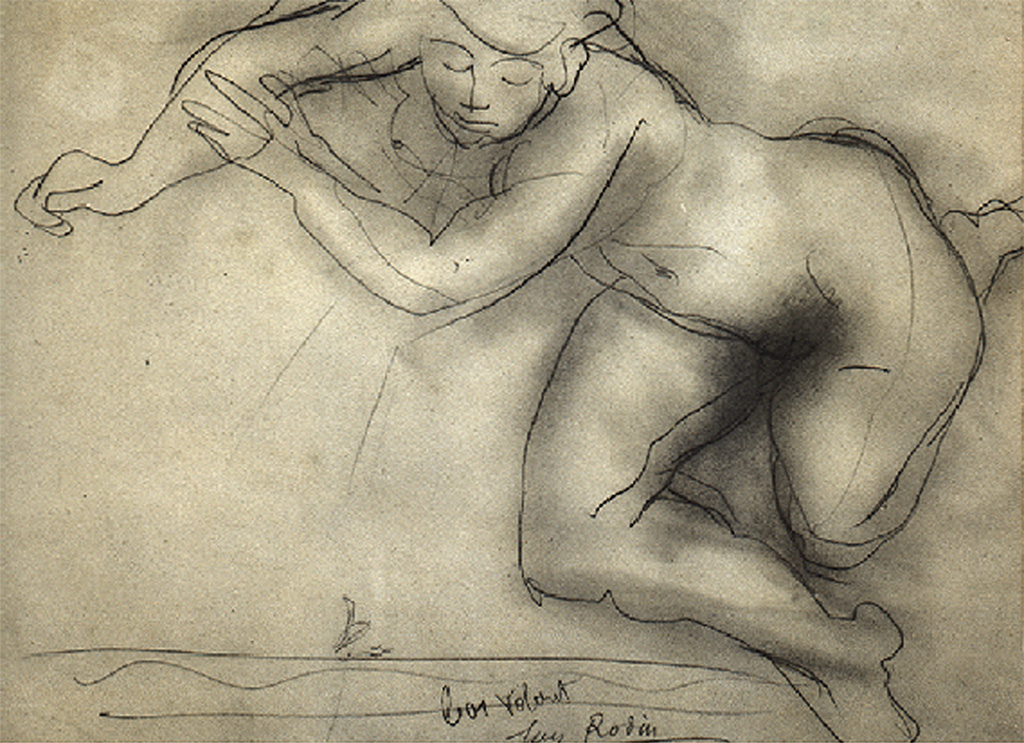

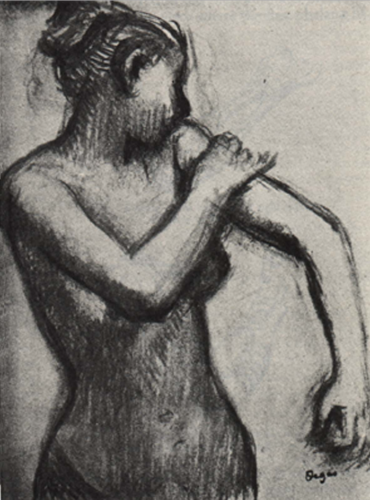

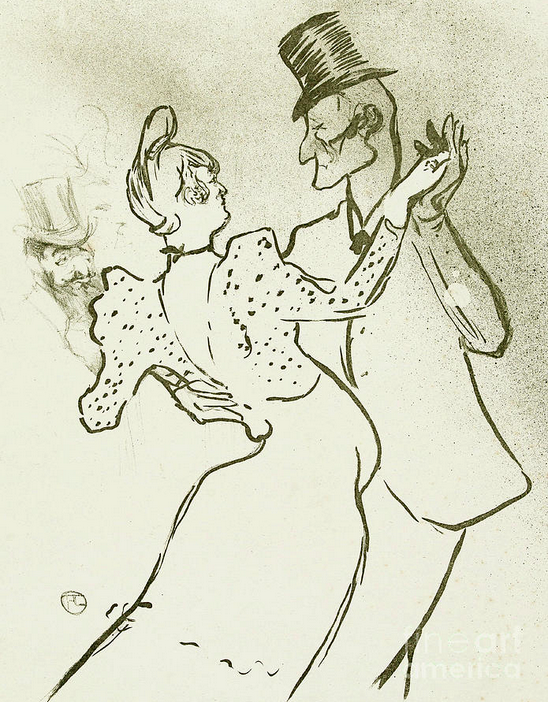

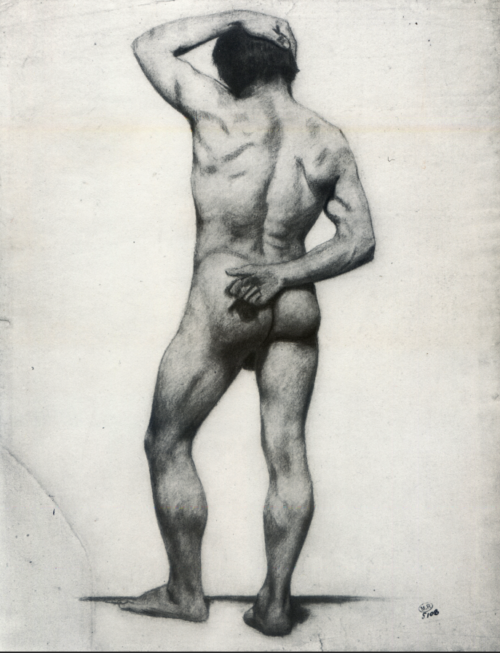

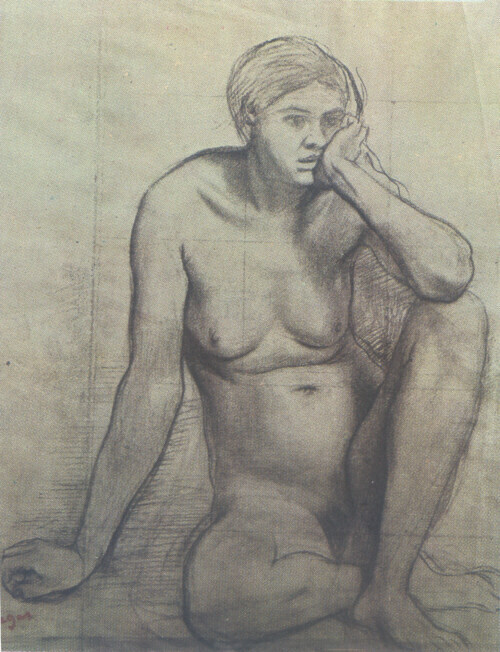

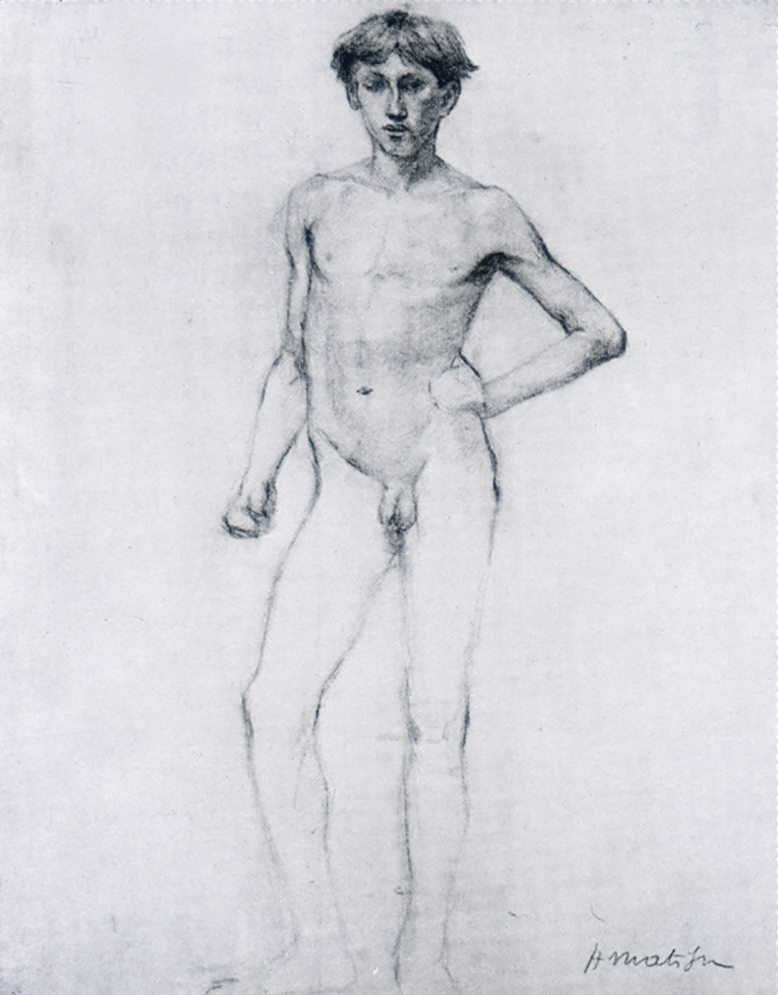

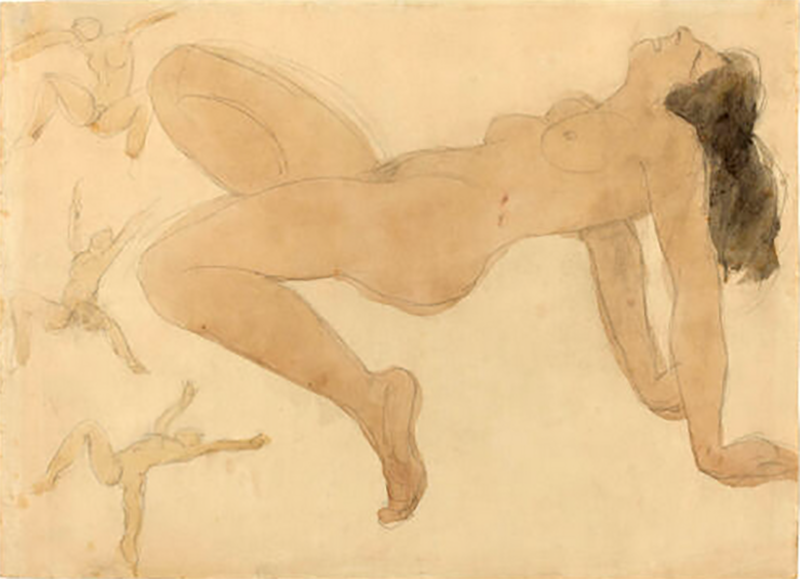

His claim had a history. In the late 1860s. a number of young artists saw a threat in the degree of realism manifested in images taken by the recently invented camera. The approach they chose for countering it was purely conceptual. It was based on a two step rationalization. First, they argued that realism of photographic images was such that it deceives the eyes and, second, that deception is “immoral”.

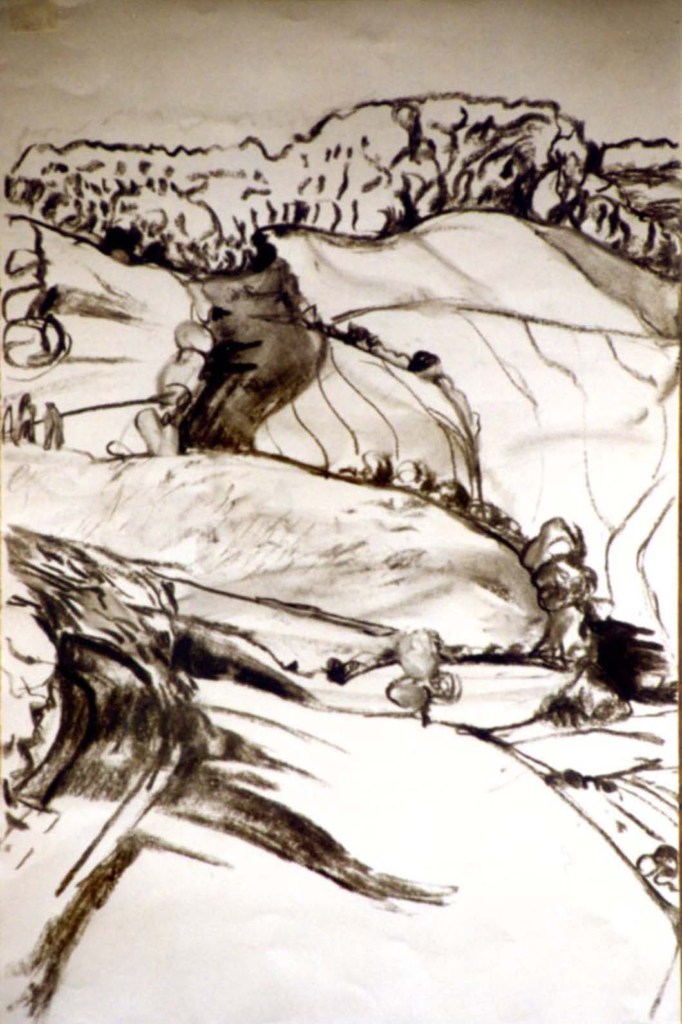

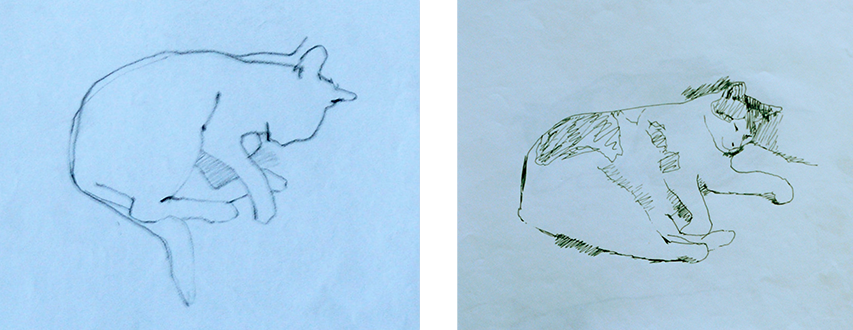

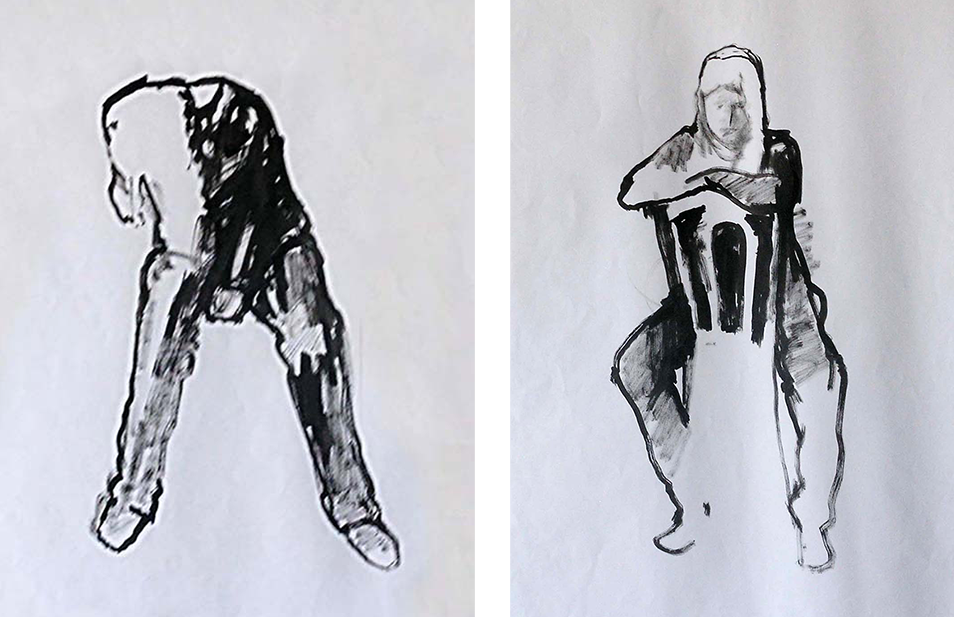

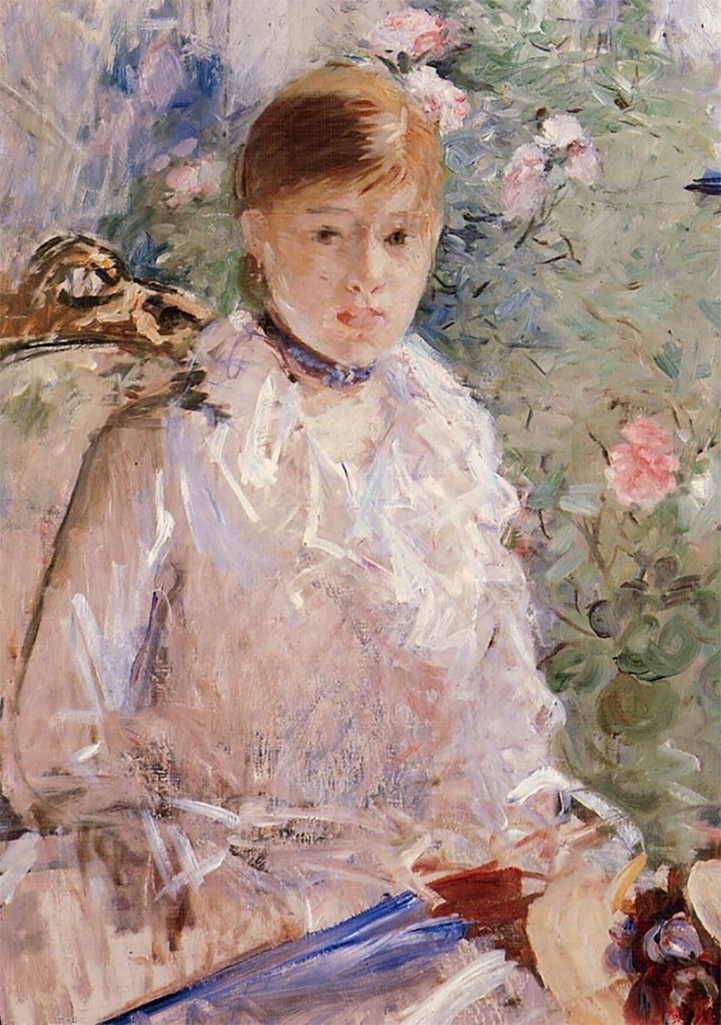

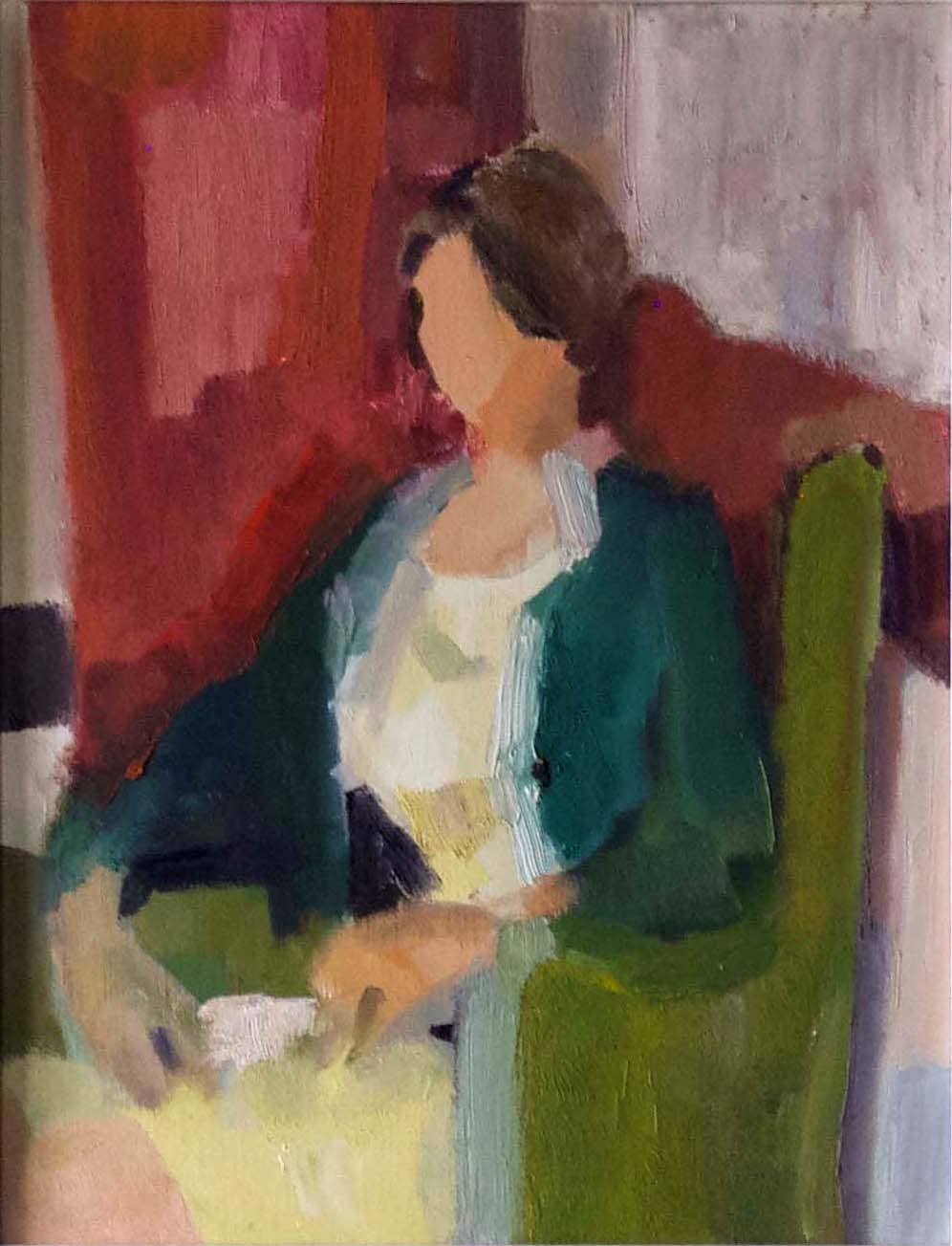

The way these artists, later known as the Impressionists, sought to avoid analogous immorality in their own figurative paintings was to emphasise the reality of the actual picture surface. Their main strategy for doing this was accentuate “surface texture” and “personalised mark-making”. Luckily for the history of painting, one outcome was that they discovered the exciting potential of exploiting the dynamic relationships between the reality of the picture surface and the illusion created by the figurative aspects of their work.

.

.

Two new developments

.

.

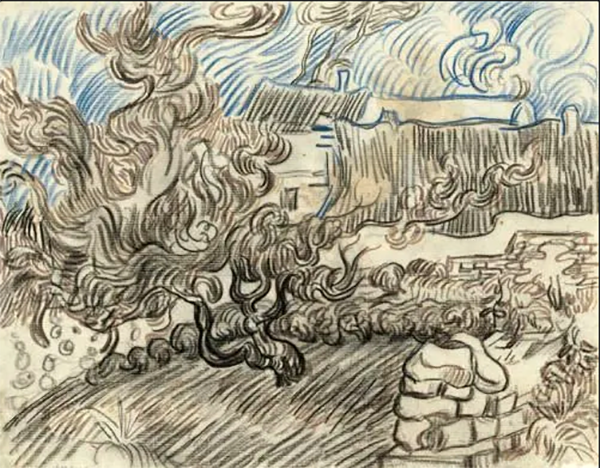

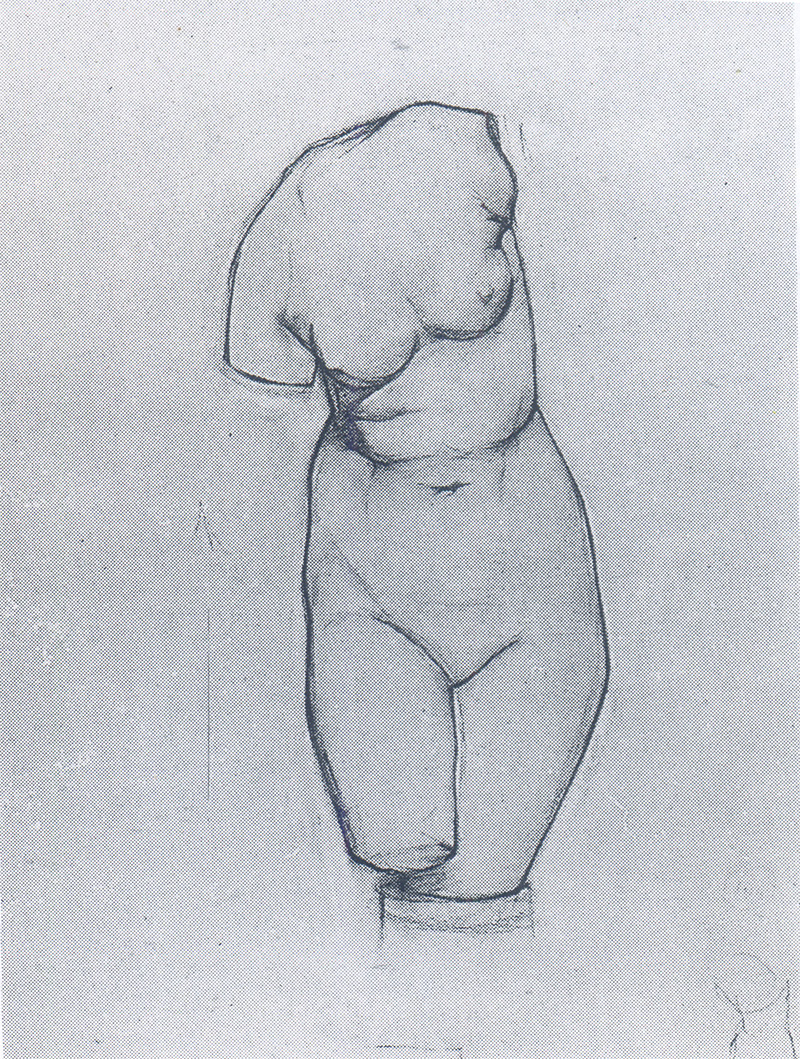

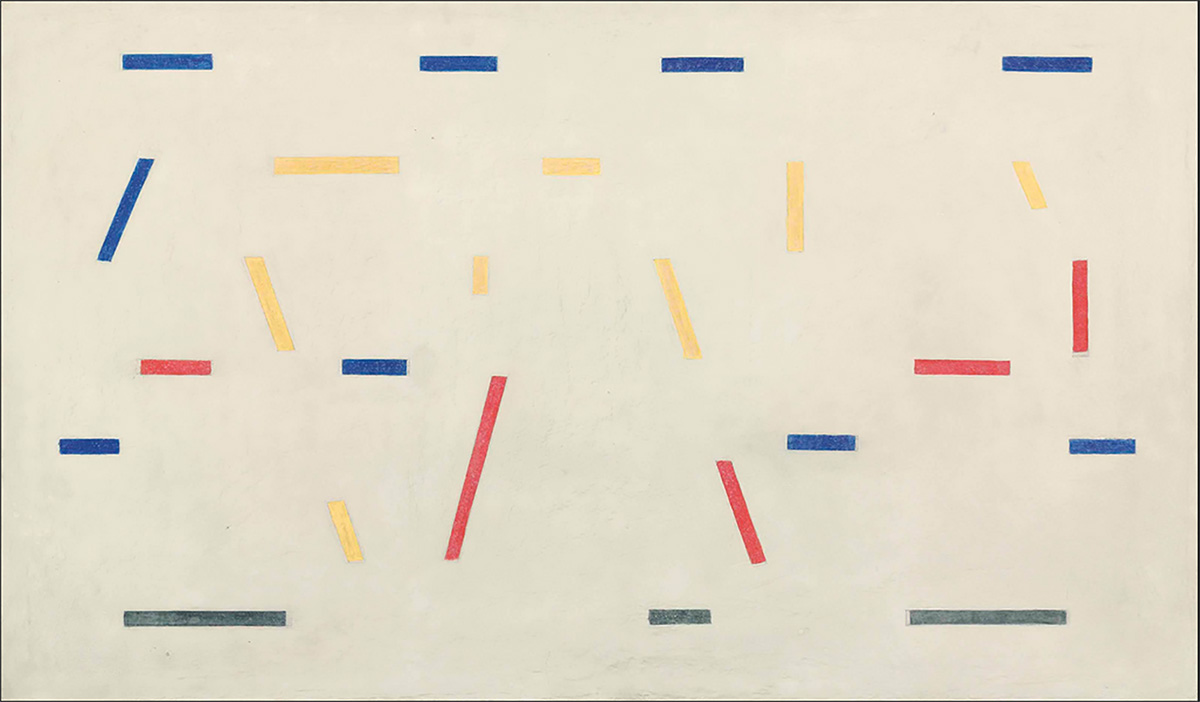

In the course of time, the successors of these early Modernist painters discovered that figuration is not necessary for creating illusory pictorial space. They found that perceptions of it could be evoked in non figurative paintings, by means of “cognitive cues”, the most important of these being “overlap” and depth-indicating “diagonals”.

.

.

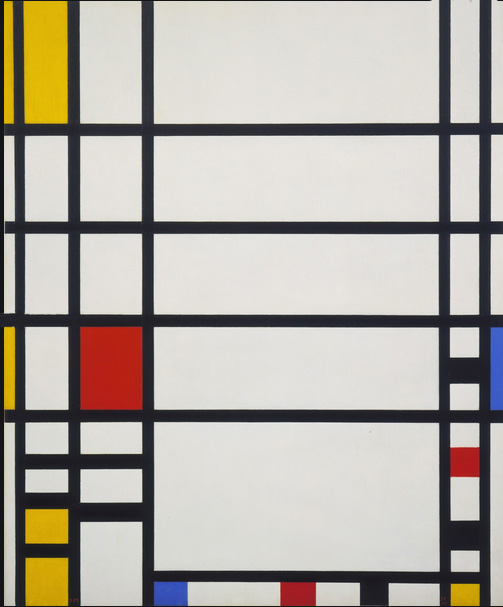

However, despite the exciting possibilities offered by real surface/illusory pictorial space dynamics, Piet Mondrian and other purists could not help concluding that any kind of illusory pictorial space was a “deception” and, accordingly, both “immoral” and to be avoided at all costs. Nor did they consider this to be a trivial matter. Mondrian permanently broke off his close, working relationship with Bart van de Leck because he had included a diagonal in one of his paintings.

Poor Mondrian had to soldier on alone. At times he must have felt despairing. However hard he tried, he could not find a way of altogether eliminating perceptions of illusory pictorial space. Eventually, his deeply religious worldview rescued him. It suggested a way of rationalising himself out of the morality problem, namely, to rename the “pictorial space” that he was unable to eradicate as “spiritual space”.

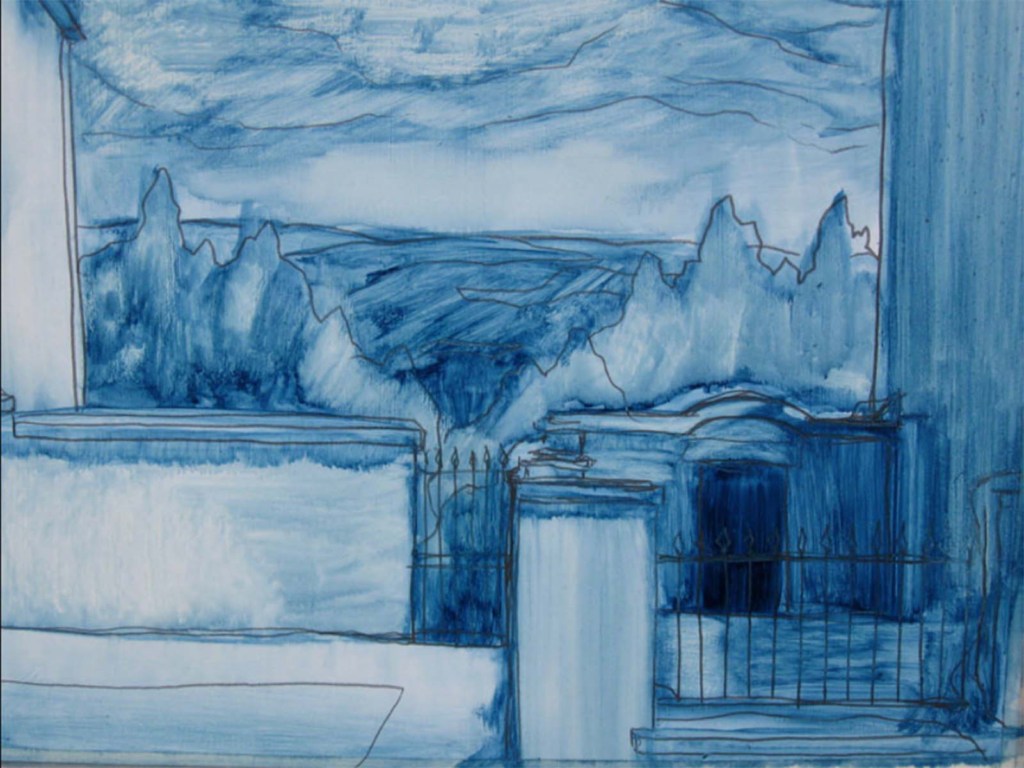

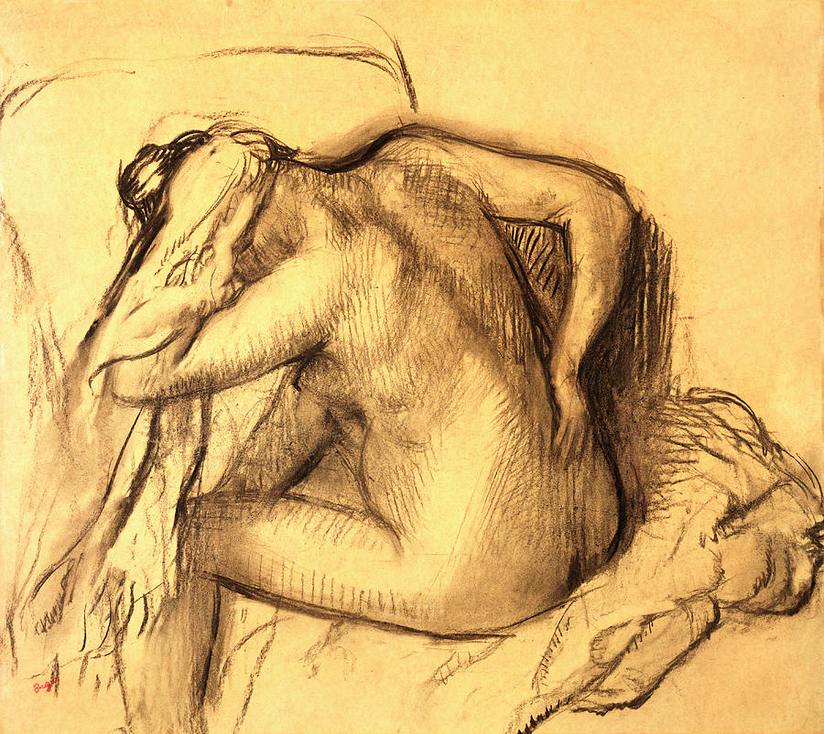

An illusory space within the picture surface

Seemingly unaware of Mondrian’s discoveries, Greenberg discerned what he described as “a space withing the picture surface” in the paintings of Jackson Pollock. This he argued was fundamental different from the “illusory pictorial space” found in the work of his Modernist Painter predecessors. However, although influential for a number of years, his claim did not convince number of later artists and theorists. Although these had no difficulty in seeing the space that Greenberg has identified, they insisted that it was illusory and they were right to do so. We now know that they were seeing was the same kind of illusory pictorial space found in the the“vase/face illusion”, in which the vase can be perceived as being either in front of or behind the inward looking faces .

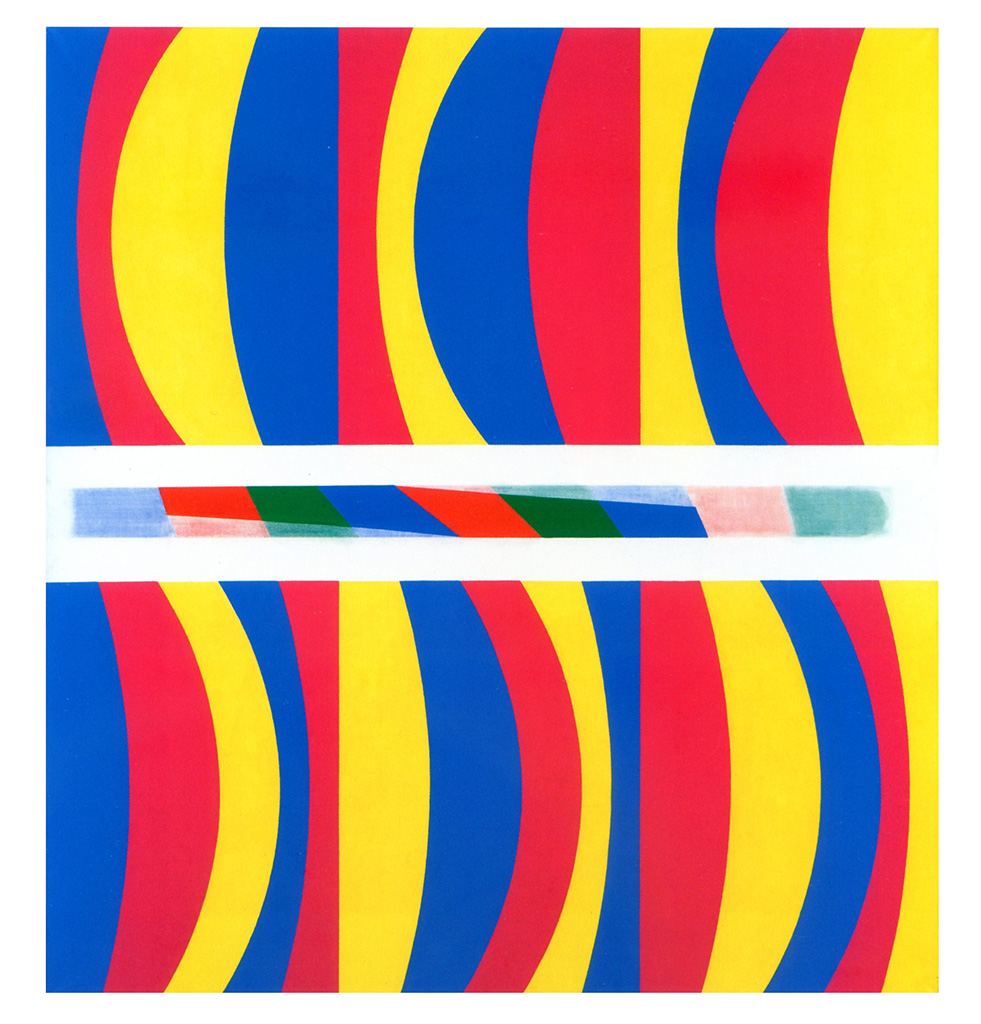

The problem that now arose was that this kind of illusory space provoked an optical disturbance of a kind that some saw as an undesirable (described in the chapter on “negative spaces” in “Drawing on Both Sides of the Brain”). To remove this in the interests of creating a pure, undisturbed colour experience, artists of the 1950s and 1960s, felt obliged to eliminate all traces of Greenberg’s “space within the picture surface”.

.

.

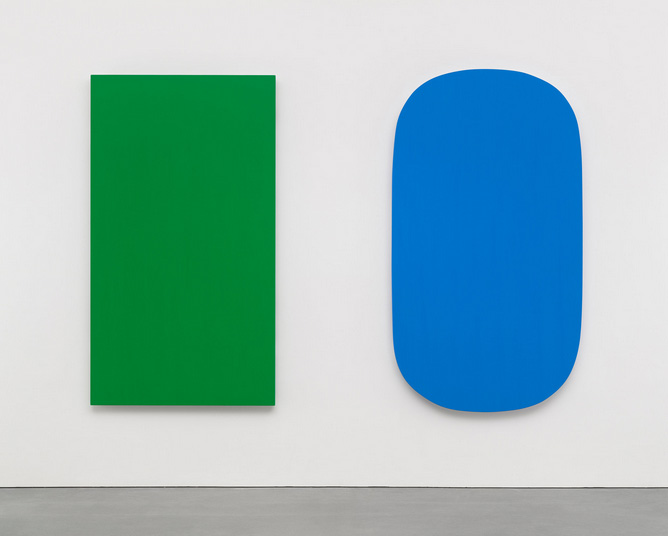

However, when they tried to do so, they found the task they has set themselves to be more difficult than they had bargained for. Indeed many decided that they were faced with an insoluble problem. They had come to the conclusion that, as long as there is more than one region colour on the picture surface, there is no way of avoiding some degree of visual tension. The reason was no longer necessarily the repeated colours of Mondrian and Pollock, it could also be the figure/field separation that occurs at the earliest stage of perceptual processing, in which the object (figure) is picked out at the expense of its context/background (field). In the view of artists like Ellsworth Kelly, the only remaining way of producing pure colour experience would be by means of single colour paintings. As these could be described as “coloured objects hanging on a wall”, the question that then arose was whether they should be classified as “paintings” or as “sculptures”. Many seem to have plumped for the latter.

.

In 1968, the Museum of Modern Art in New York provided the art world with what turned out to be a watershed exhibition. Its title, “The Art of the Real” ,was deeply significant. From the conceptual point of view, it signed the death knell of one of the most influential strands of the broad tapestry of “Modernism in Painting”. For those that believed this to be the only strand, the future of painting had to be in some manifestation of “Post Modernism”.

None of this necessarily deterred artists from carrying on regardless with all the different possibilities. They will always be free to embark on new explorations of:

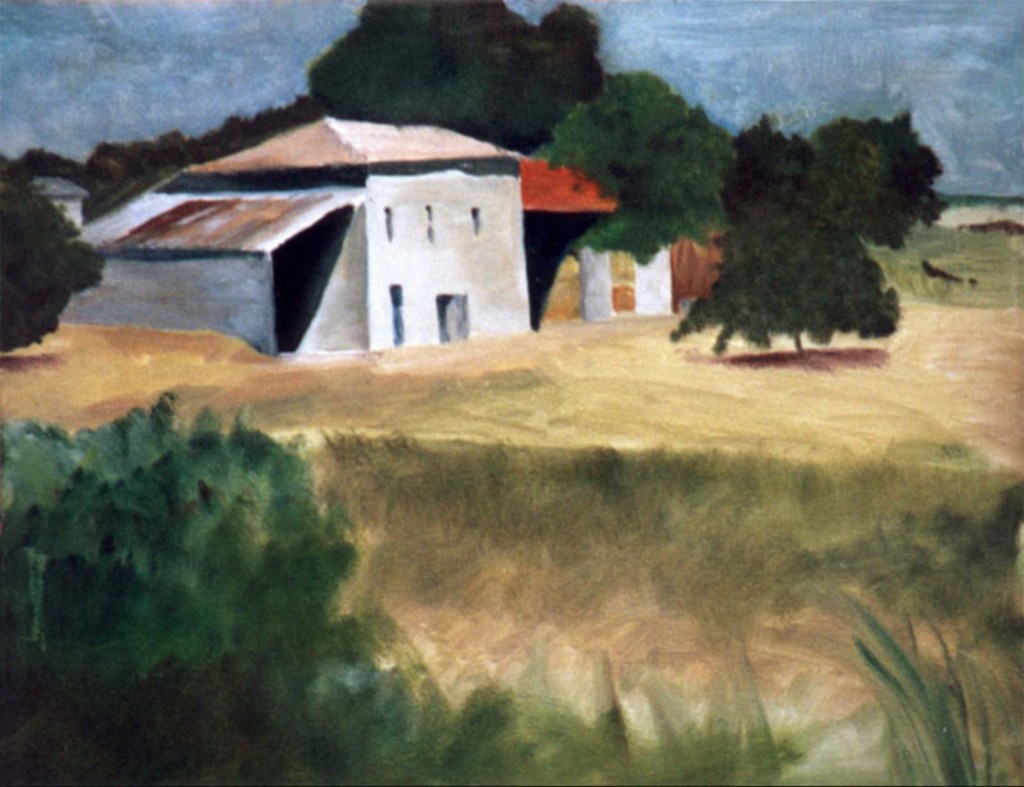

- Trompe l’oeil

- Real surface/illusory pictorial space dynamics

- Space within the picture surface

- Explorations of the “art of the real”.

All are to be found in work produced up to the present day.

Footnote 1

As a footnote I think it worth mentioning that the issues discussed above were central to the teaching of both my main mentors.

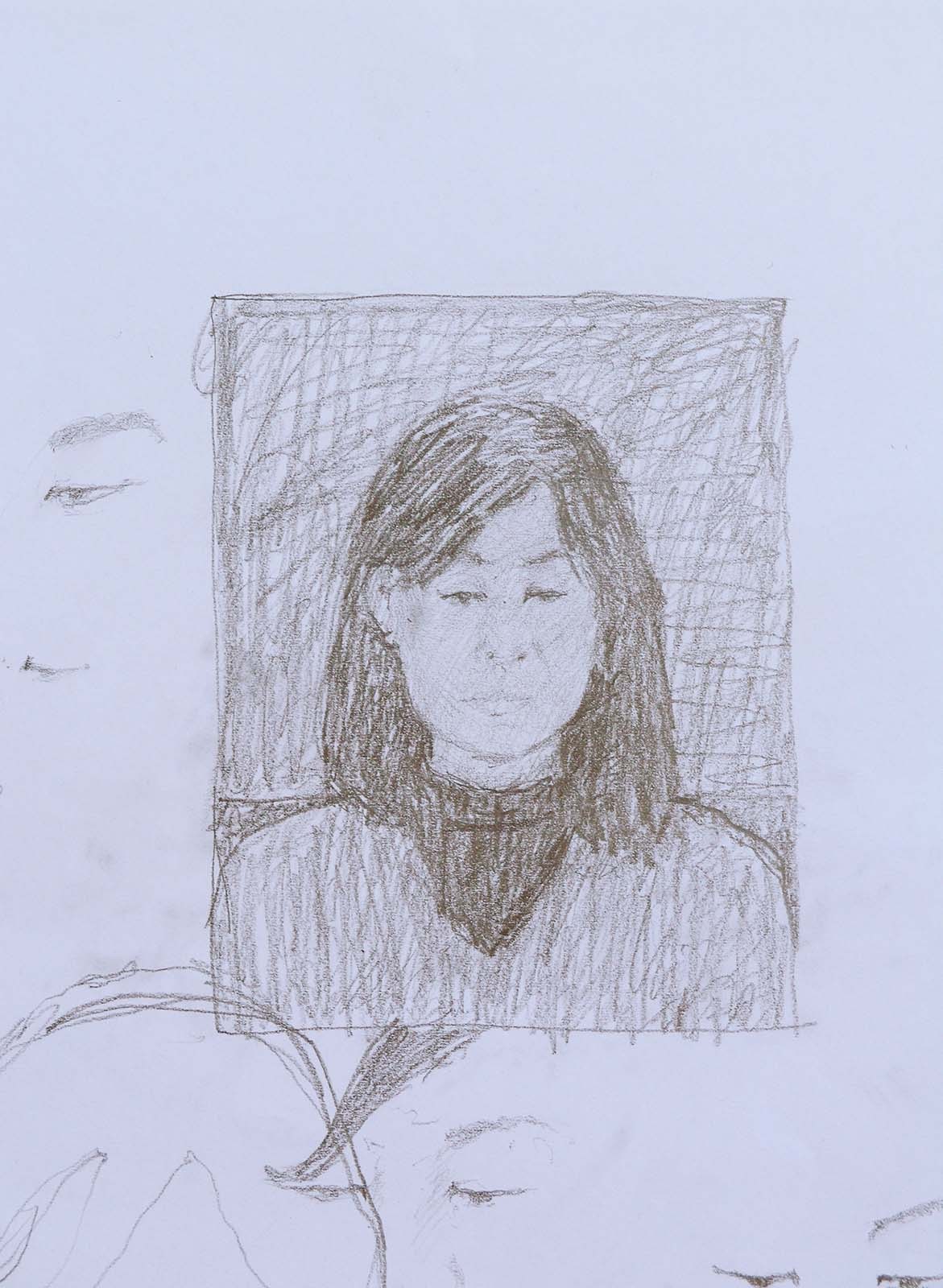

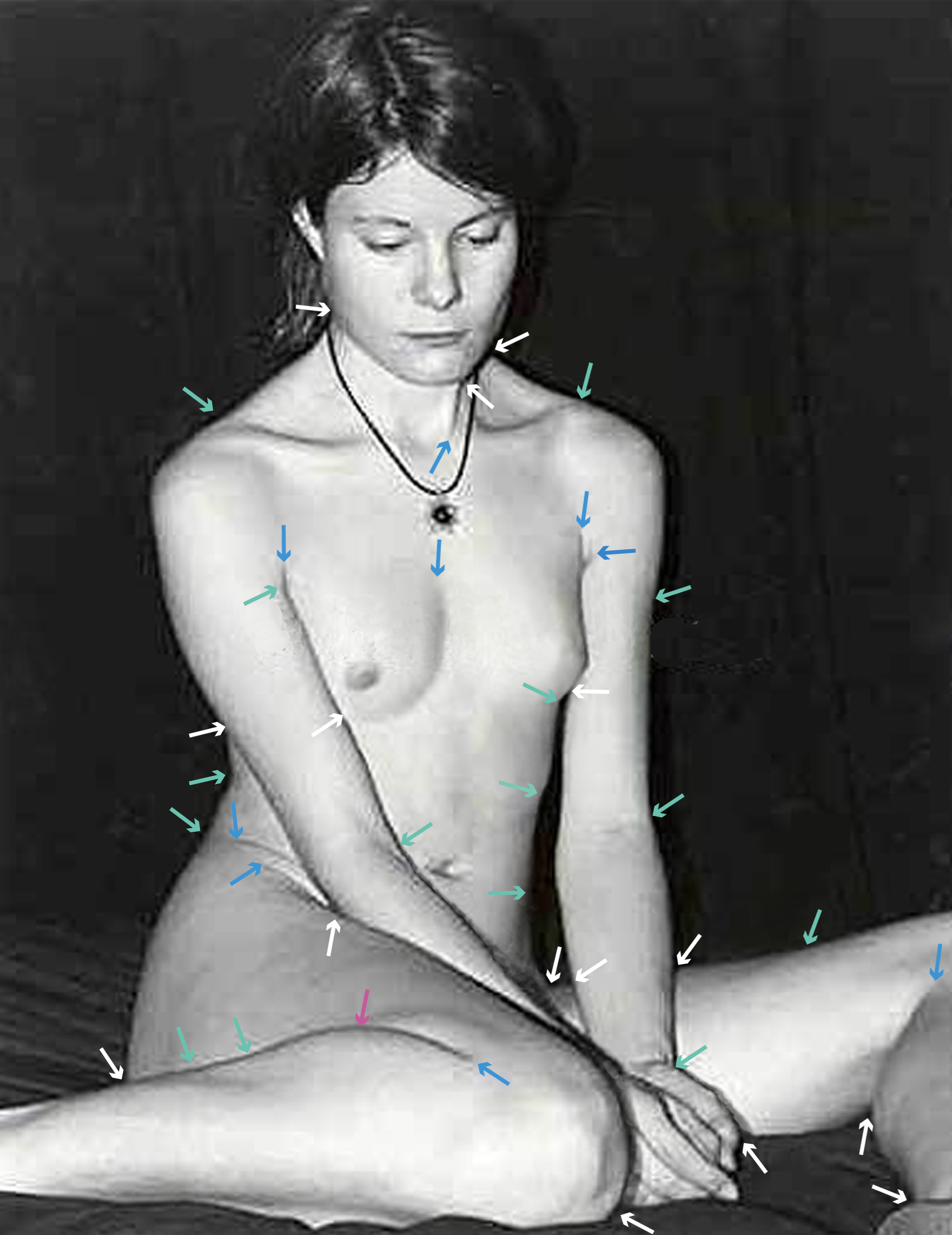

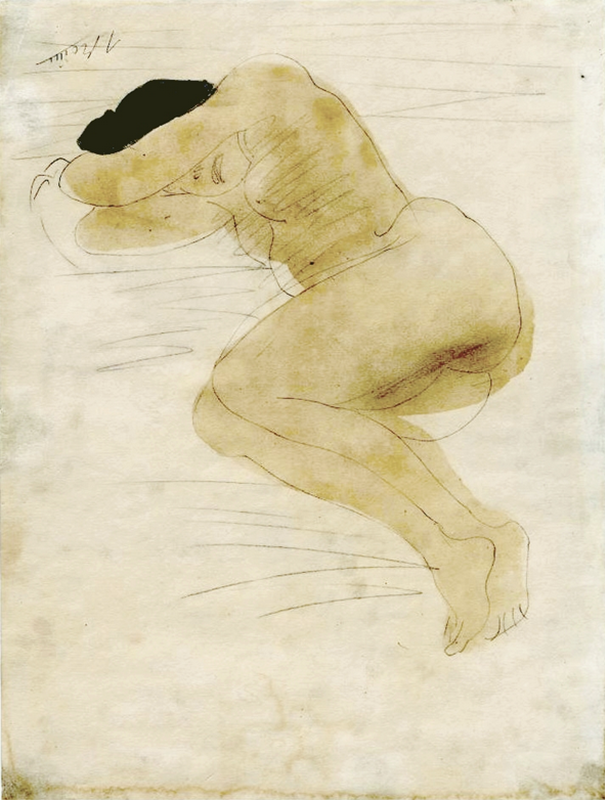

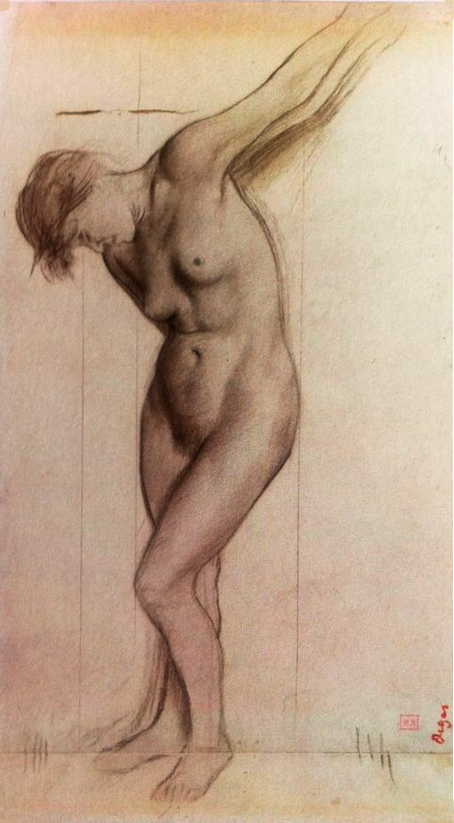

- Professor Bohusz-Szyszko felt the main importance of his rules was that they ensured what he described as “the integrity of the picture surface”.

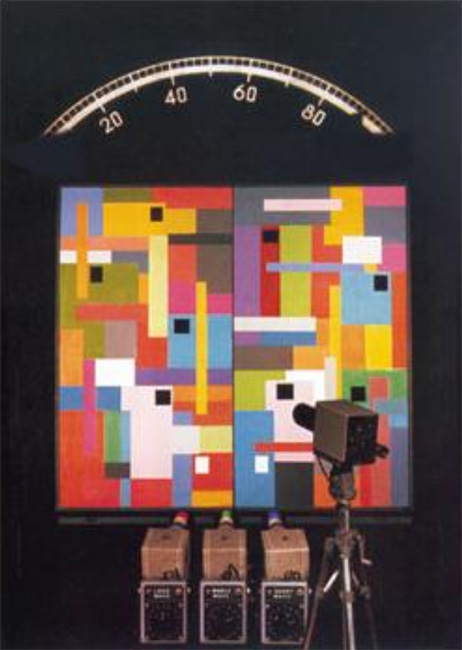

- Michael Kidner followed Greenberg and Pollock in believing in the importance of eliminating illusory pictorial space, as defined by them. He also made good use of what they described as “the space within the picture surface”, in other words what I have been likening to the illusory pictorial space exemplified in the vase/face illusion.

Footnote 2

Incidentally, Professor Bohusz-Szyszko told me that the fact that his rules ensured the “integrity of the picture surface” was one of the main virtues of the dogmas he shared with his students is. According to him repetitions of the same colour in different parts of a panting broke the “integrity of the picture surface“, either by jumping out in front of it or by creating the illusion of holes within it. We now know that this theorising was wrong. As explained in many places in my books, what they jump out of is illusory pictorial space. What actually happens is that they are perceived as jumping from surfaces in an illusory world, and integrating with the actual picture surface. From the practical point of view this theoretical distinction does not matter for in both cases the outcome is that the eye and the brain are confronted with incompatible and therefore disturbing perceptual cues.