The word “abstract”

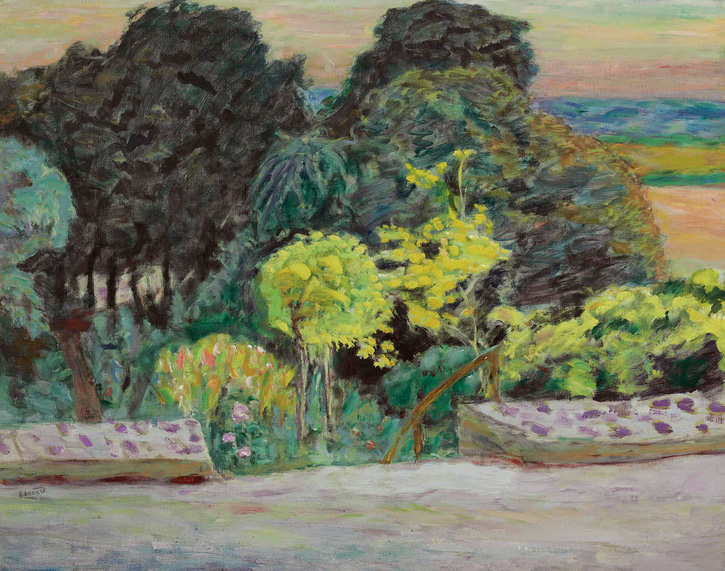

The word “abstract” is commonly used to refer to a wide variety of paintings. Therefore, there is clearly some confusion as to precisely what it means. This is partly because its usage by artists and critics has evolved over the years and partly because its subtleties have been degraded by an uninformed public. One unresolved issue is where to draw the line between “figurative” and “non-figurative”. Few nowadays would describe Paul Cézanne as an abstract artist (see image below), yet his working philosophy exemplifies the original meaning given to the word.

_________________________

This Post, like many others, is an illustrated excerpt from “Having fun with creativity”, Chapter 10 of “Fresh Perspectives on Creativity”. What is meant by “having fun”, is enjoying a process by which thoughts, however trivial or wrongheaded, lead to a mushrooming of other thoughts and, thereby, to an exploration of issues that otherwise might be passed over. What follows, not only touches on the subjects of abstraction and construction in painting, but also how these relate to the processes by which the eye/brain systems synthesise meaning from visual input. The four sections are headed: 1–ABSTRACTION, 2-CONSTRUCTION, 3-CHANGES IN MEANING and 4-IMAGES OF PAINTINGS (illustrating, “Abstracting the essence” and “Constructing from the basic building blocks of visual perception”).

1-ABSTRACTION

What is an abstract painting?

So what qualifies as being an abstract painting? An explanation as to why the word “abstract” was chosen in preference to other words offers a start to the answer. Why not “extract” or “subtract”? It is worth asking such questions because doing so can help a process of refining understanding. It enables the use of same/difference judgments within the domain of words as a means of creating and/or nuancing our sense of their meaning. Thus:

- The word “extract” means take something out of something.

- The word “subtract” means take something away from something.

In either case the original something is diminished. In contrast:

- The word “abstract” means distilling the essence of something, with the implication that this can be done without loosing essential meaning.

Accordingly, the word “abstract” seems best of the three because it implies the possibility of finding what is valuable with the least collateral damage. This is why it was chosen.

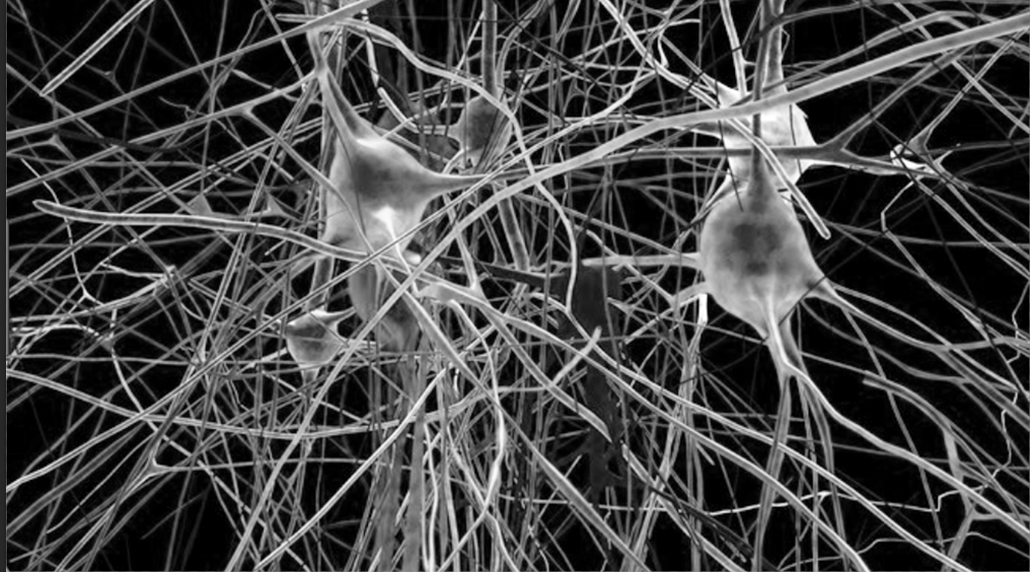

Eye/brain issues

However, there is still much ambiguity that requires clarification. If we take the example of the “abstract” of a scientific paper, it is easy to see that however well written, something must have been lost, since otherwise there would be no need for the paper itself. In the case of artists’ abstractions from natural scenes, the situation is less clear, particularly since the image of every scene that comes to our consciousness is produced in the first place through the mediation of eye/brain processing systems that arrive at their conclusions by means of a complex blend of selective and constructive processes. We look at a coffee mug differently according to whether our intention is to drink from it or to make a drawing of its outline. When we want to drink from it, we will normally bypass all information about it except that which is necessary for picking it up and putting its brim to our our mouth. When we draw its outline, we need to make judgements of relativities of position, length, orientation, curvature, etc., and we can safely ignore the information needed to drink from it.

Nor, in this context, should we ever forget that what we experience as “seeing” depends heavily on information coming from non-visual sources accessed (a) by other sensory systems and (b) by memory-stores that have been built up and refined during a lifetime. Thus, both the knowledge that it is coffee time and the smell of coffee, provide context that helps our visual systems to home in on the coffee mug. When we are confronted by a landscape, the way we look at it and the information we derive from it are determined by a mixture of current contingencies and our life’s experience. No two people would find the same essence in it. Indeed, it is now clear that in creating conscious visual experience, our eye/brain systems ignore a great deal more of the information coming into our eyes than they make use of. A mathematician might suggest that they ignore an infinite amount of it.

So how do these facts help us to think about looking at paintings? What differences are there between looking at a real world object and an image of it found in a painting? Generally speaking, when we look at a painted image, situated in illusory pictorial space, the information available will be much less than can be accessed from the real world object. For example, no matter how photographically realistic it may be, an image painting onto a flat surface will not provide the eye/brain systems with the kind of spatial-depth information that is created by means of either stereopsis or motion parallax. Likewise, a sketchily produced portrait will contain much less information than an actual face.

But what is the effect of this impoverishment of available sources of information on the efficiency of the eye/brain visual systems? Does it make their task more difficult? Not necessarily so. As indicated above, all correct classifications are achieved without taking a great deal of potentially relevant information into account. It is worth remembering that efficiency can be defined as achieving an objective with the least possible effort. In the case of the impressive efficiency of eye/brain systems, this means overlooking as much visually available information as is feasible. If we take full advantage of contextual information coming both from other sensory systems and from memory, it can mean overlooking practically all of it. Elsewhere, I give the example of a blur of redness being a sufficient cue to identify a familiar dress in a familiar wardrobe in which it is known that no other red dresses have been placed.

This impressive degree of parsimony has interesting implications for artists. For example, does it mean that a blur of red could adequately represent the dress in a painting? The answer to this question depends on what is meant by the phrase “adequately represent”. In the obvious sense, the answer must be “no”. Nobody would expect the woman in question to reach out for the painted image of a red dress in the wardrobe in the expectation of being able to wear it. On the other hand, the red in the painting might trigger either “feelings” or “memories” associated with the history of the dress that the real dress would not. If it does, how could this influence the experience of people looking at paintings? Two questions, bring us nearer to an answer:

- Could feelings be stimulated by a particular red as itself. For example, it is perfectly possible for the colour of an individual stick of chalk pastel to access deeply embedded associations that trigger powerful emotions. If so, could these be added to the experience generated by a pastel painting of the red dress? Of course they could: I thought of the example because I know of an artist for whom love of her pastel sticks was integral to her way of making paintings.

- If the the act of seeing the patch of red paint triggers “memories”, how much information could be added from memory stores? And, would these additions be more or less authentic than the information that would be accessed by the woman, if confronted by the actual dress? Since, the real object presents a maximum of information about its characteristic, there is no doubt about the theoretical answer to this question: the real dress has every advantage. But the question for the artist is not whether the red dress would provide more information, but how much of it would be used in practice and for what purposes?

Remember that efficiency can be defined as getting the best results by means of the least amount of effort. In the case of locating the real dress in the real wardrobe, this means identifying it with the least amount of looking. As explained above, the eye/brain systems regularly achieve wonders of parsimonious looking by making maximum use of “context” and “memory stores”. It follows that, the very familiarity of both the dress and its location would make it possible to achieve the goal of finding the dress while overlooking the totality of information other than the blur of redness.

However, the question arises as to whether this massive overlooking mean that the pictured dress might have the advantage over the real one when it comes, either to the amount of information about the dress actually acquired or to the potential for providing stimuli for the creative imagination? In both cases, the answer must be in the affirmative, since it could be argued that a pictured dress:

- Would provoke the eye/brain systems into extra analysis, on account of its being less familiar than actual dress.

- Would leave extra room for flights of the imagination, on account of its lack of interpretation-constraining details.

In other words, there are good reasons for concluding that, in practice, if not in necessarily in theory, an image of a depicted object perceived as being in illusory pictorial space will regularly, if not always:

- Provide the eye/brain with more information than the real world object it represents.

- Act as a better catalyst for the creativity of the imagination.

Needless to say, this is one of the many advantages that paintings have over nature.

The influence of others

Another possibility is that the dress-owning woman may fail to make a connection between the patch of red in the painting and the dress it was intended to represent, but that a friend does make a connection. If the friend shares her experience with the woman, by doing so she will be adding another level of context and, thereby, in all probability, causing a change in the meaning of the patch of colour for the dress-owning woman. Significantly, the revised significance could be achieved without making any changes to the actual colour.

But this is not all. One thing of which we can be quite certain of is that the representation of the dress in the head of the friend will be very different to that in the head of its owner. There is no possibility that both will have the same associations between the dress and happenings in their very different life stories. The interesting implication for artists is that what applies in the case of the two friends, also applies to them. When they apply a colour to a painting, they can have no way of knowing all the associations it might trigger in any one other person. Speaking generally, all human beings can say or do things that act as catalysts to the experience of others that are inaccessible to themselves. Indeed, it is difficult to see how communication between individuals could take any other but in this essentially catalytic and creative form.

2-CONSTRUCTION

But all this talk about “abstraction” in paintings and by the eye/brain systems has a soft underbelly for, as we all know, for some time now, the word “abstract” has been routinely applied to paintings that have absolutely no reference to nature, let alone to some essence extracted from it.

In the early 20th century, a number of painters and sculptors acknowledged the significance of this flight from representation by calling themselves “Constructivists” . These pioneers of non-figurative art adopted a radically new approach to their work that had much in common with the physicists of the day, who were on the trail of the building blocks of matter and the principles by which they are combined. Thus, the artists sought to identify the “primitives” of visual perception and to find objective principles for assembling them into art works.

By the fact of approaching paintings in this way, these artists saw themselves as challenging the long held assumption that painting should start from nature. Accordingly, it would be inappropriate to describe their work as distillations of it essence. For a growing number of them, including Kupka, Malevitch, Kandinsky and Mondrian, an alternative was needed that would be founded on a combination of the most basic elements they could think of and simple principles of construction. Over the years, this change of emphasis was reflected in the emergence of a host of different words or phrases to describe how different artists approached building on these foundations – “Constructivist”, “Non-objective”, “Concrete”, “Op”, “Systems”, etc., but all could be places under the umbrella of “Constructivism”.

3-CHANGES IN MEANING

As time passed the situation became more and more complicated. On the one hand there were critics trying to provide more precise classification and on the other there were artists exploring an ever expanding range of possibilities. Distinctions got blurred and terms like “Abstract Expressionism” confused the issue. The artists who were known by this name, were no longer abstracting from nature but rather attempting to make manifest their innermost feelings or allow universal forces to become manifest through them. In this situation, while artists were likely to choose and cling to one or other of the cavalcade of different meanings, the generality of people adopted the catch-all, common usage of today. For them the word “abstract” means anything that is not too closely tied to representation.

Conclusions

Students sometimes ask me to explain “abstract art” to them. As this request is almost invariably made by people whose focus has been on representation, I tend to answer in terms of the origins of the word. I point out that artists living in the second half of the 19th century, influenced by recent developments in the science of visual perception, became aware that all paintings could be described as an “assemblage of regions of colour on a picture surface”,* as interpreted by eye/brain processing systems. Once this conceptual step had been taken, it was only to be expected that, for some artists at least, the idea of looking to nature as the fount of all inspiration was bound to be questioned. From then on, it was only a matter of time before many artists either loosened their ties with representation or completely cut themselves off from it.

As for deciding which word we should choose when talking about any particular painting or group of paintings, including ones we have painted ourselves, my answer would be to take your choice in the light of the considerations discussed above. Perhaps, the main objective should be that you yourself understand the issues, at least well enough to be able to explain them to anyone who asks questions about your work. Meanwhile, the general public will continue to think of “abstract” as more or less anything non-figurative and pretty well everyone will have personal opinions about what counts as figurative. The difficulty lies in deciding on which point on the figurative/non-figurative continuum.

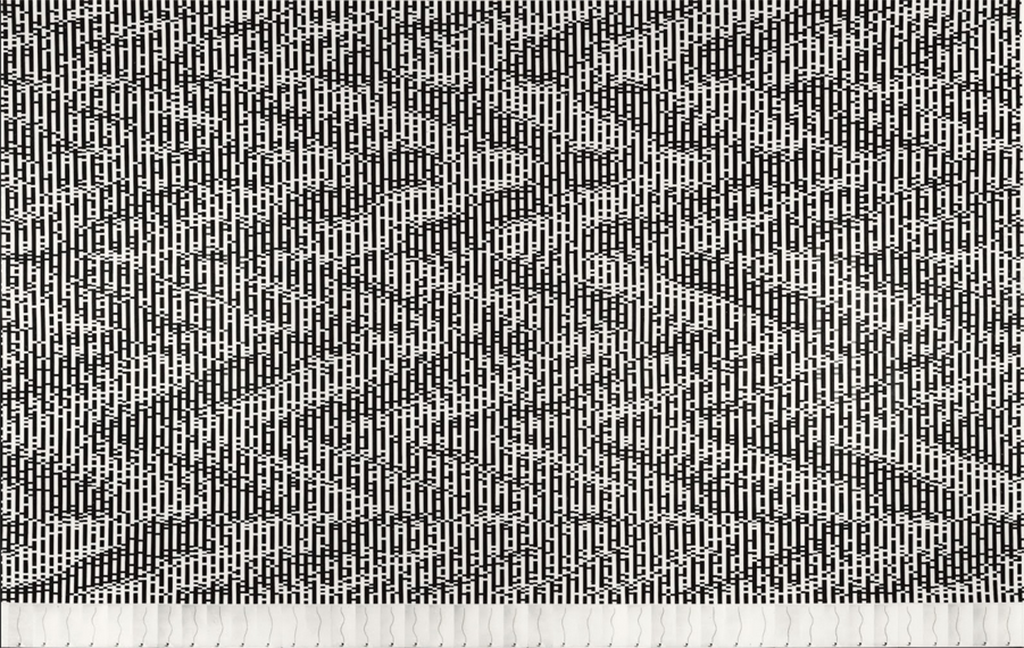

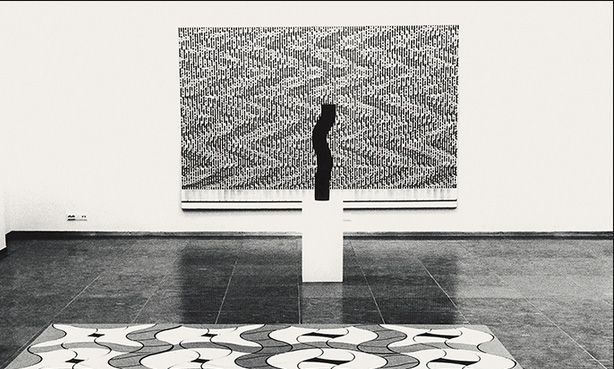

4-IMAGES

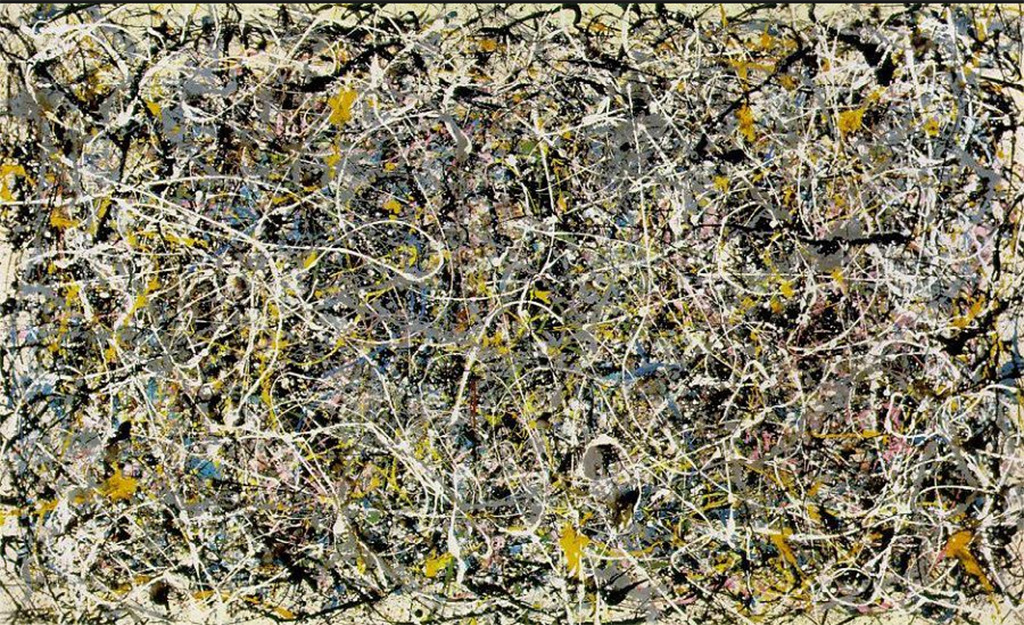

Abstracting the essence

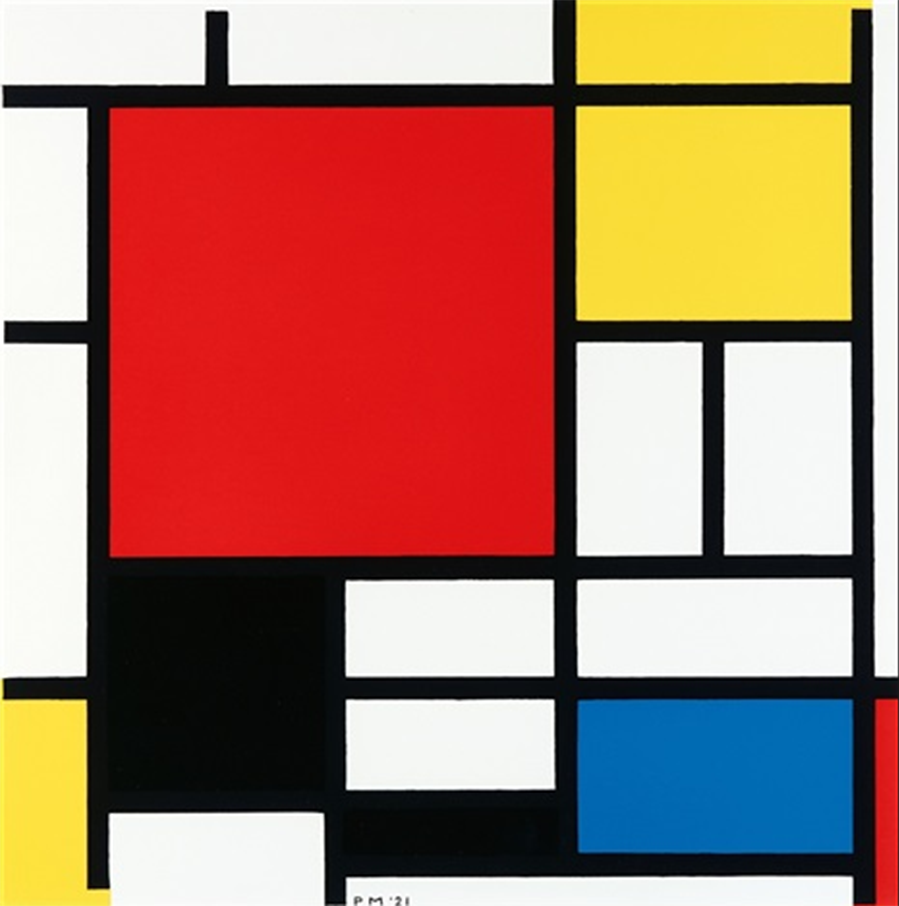

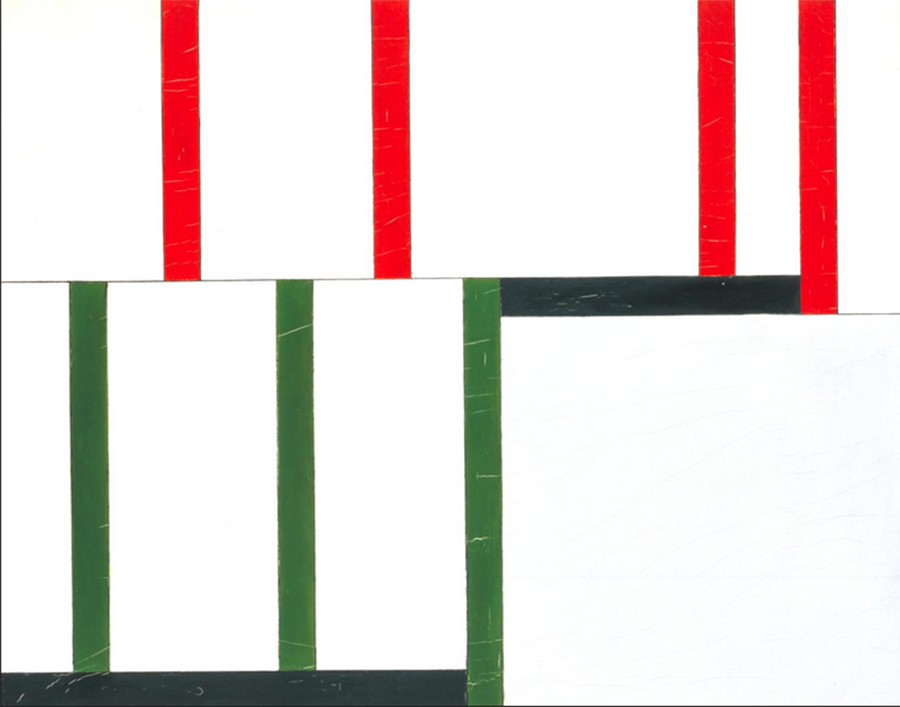

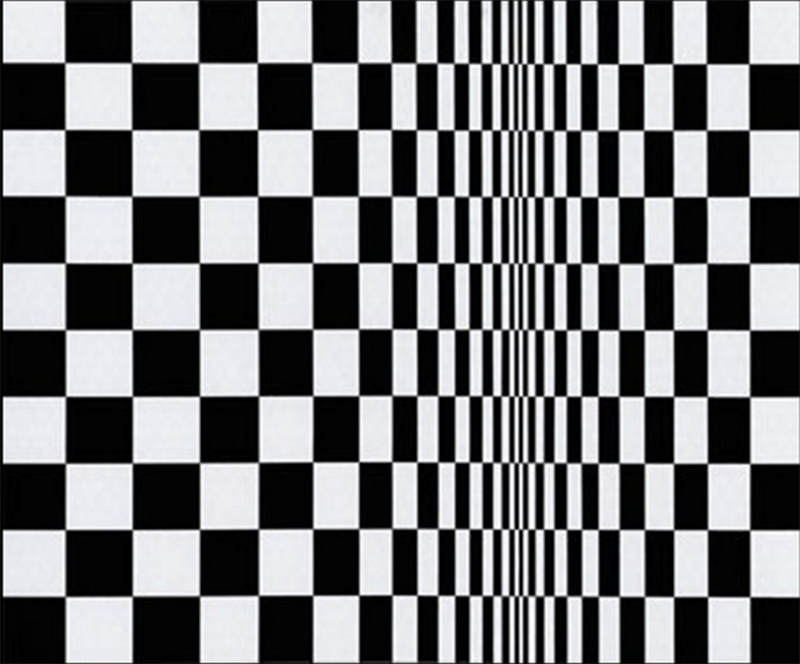

Constructing from the basic building blocks of visual perception

* Quotation from the Nabis artist Maurice Denis.

** Quotation from Bonnard.

_________________________

Other posts from “Having Fun with Creativity”, Chapter 10 of “Fresh Perspectives on Creativity”

- Playful fancies as a stimulus to creativity

- An inspirational story: a child draws a potato

- The case for being a flat-earther:

- The nature of truth

- Tapies advocates playing games

- Cézanne fall short

- False confidence

- Self deception

- Free will and determinism

- Abstract and Constructivist: some definitions

Other Posts from “Fresh Insights into Creativity”

- Chapter 6 : “The Modernist experiment.

- Chapter 7: “The first Modern Painter”: A surprise suggestion.