A confluence of issues

This Post introduces Chapter 22 from my book “Painting with Light and colour”. It uses one of my paintings to discuss many issues that relate to viewing conditions. These all apply to all paintings, but it is difficult to find information about them in other books. Indeed, it was not until I began work on paintings including numbers of thin lines that I became fully aware of many of them. My awakening was a result of the coming together of many strands of the story I have been telling in my series of four books.

- The dogmas of Marian Bohusz-Szyszko (see Chapter 1),

- The “systems” ideas of Michael Kidner (see Chapter 8 of my book on “Creativity“),

- My interest in the debates relating to “illusory pictorial space” (see Chapters 7-10 in “Painting with Light”, the first part of this volume),

- My interest in the Modernist Painters obsession with what they described the “integrity of the picture surface”* and its dynamic implications in the history of “Modernism in Painting“**

- The use of thin lines as a means of exaggerating and, thereby, exploring “simultaneous colour contrast effects” (see previous chapter).

![]()

Important warning

In general, whenever images of paintings are transferred to the computer screen, many of their qualities are lost. Sometimes this can be an advantage, but never for paintings that follow the dogmas of Professor Bohusz-Szyszko. This is particularly true for the images using thin lines discussed in this chapter and the next. Often, you will just have to take it on trust that the effects discussed are as described.

![]()

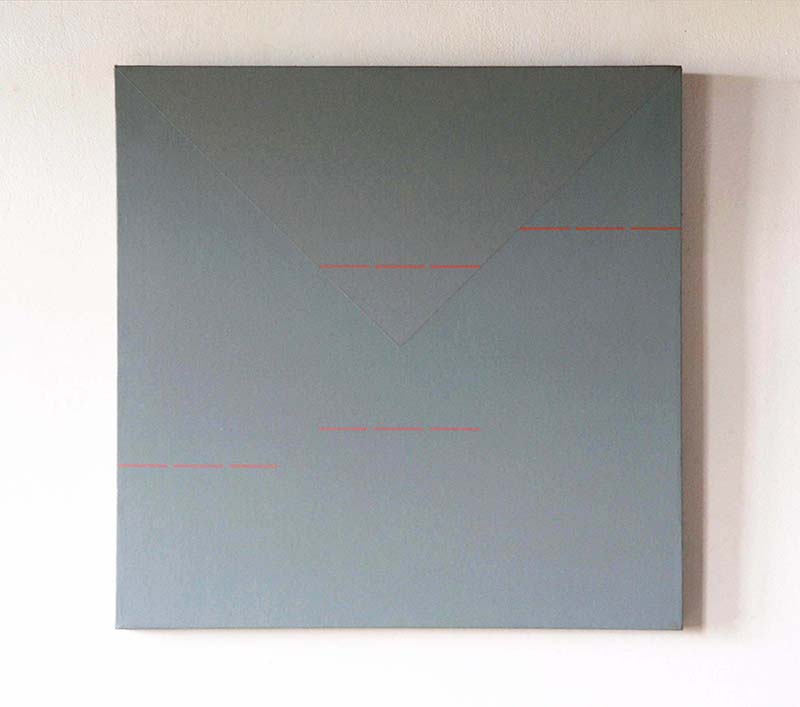

An image of a painting with twelve of orange thin lines

CHAPTER 22 – MORE ON THIN LINES

![]()

Footnotes

* If you ask Google “What is a Modernist painter”, you get the following excellet summary: “Modern art includes artistic work produced during the period extending roughly from the 1860s to the 1970s, and denotes the styles and philosophies of the art produced during that era. The term is usually associated with art in which the traditions of the past have been thrown aside in a spirit of experimentation.” However, if you had asked Manet, Cézanne, Van Gogh, Matisse, etc., etc., whether traditions of the past had been thrown aside, you would find that it was by no means all of them.

** Google says that the “integrity of the picture plane” is a phrase coined by the influential art critic Clement Greenberg in his essay “Modernist Painting”. It concerns the issue as to whether the fact of creating an “illusory pictorial space” interferes with perceptions of the “objectness” of the actual picture surface. This was a question of primary importance to the “Early Modernists” from the late 1860s onwards. For them, as explained in Chapter 6 of my book “Fresh Perspectives on Creativity”, the fact of the possibility of being aware of the actual surface of paintings was one of the reasons for what they believed to be their inherent superiority relative to photographs. Their belief was that, since “deception is immoral”, painters must avoid it at all costs. Despite the difficult-to-comprehend this questionable argument, it stuck for about a century. Thus, in the 1960s, it was still a potent aspect of the teaching of my two mentors, Professor Bohusz Szyszko and Michael Kidner. The difference between the “Early Modernists” and Clement Greenberg was that the former (and Professor Bohusz-Szyszko) thought it possible to depict illusory pictorial space without destroying the integrity of the picture surface. In contrast, Clement Greenberg asserted the impossiblilit of any such thing, as did Piet Mondrian and a number of earlier painters, plus a whole list of later artists, including Michael Kidner and Ellsworth Kelly.

As those who have read “Painting with Light”, the first Book in this Two Book Volume will realise, the early Modernists and Professor Bohusz-Szyszko got it wrong. The use of unmixed repeated colours do not disrupt the picture-surface, but rather the illusory pictorial space. They do so because our eye/brains read them as being on the picture surface and, consequently, as jumping out of any illusory pictorial space, which is allways behind it. It is thus, the integrity of illusory pictorial space that is disrupted.

![]()

Earlier chapters from “Painting with Light and Colour”:

- INTRODUCTION to Book 1- “Painting with Light”

- Chapter 1 : The dogmas

- Chapter 2 : Doubts

- Chapter 3 : The nature of painting

- Chapter 4: Renaissance ideas

- Chapter 5 : New Science on offer

- Chapter 6 : Early Modernist Painters

- Chapter 7 : The perception of surface

- Chapter 8 : Seurat and Painting with Light

- Chapter 9 : Seeing Light

- Chapter 10 : Illusory pictorial space and light

- Chapter 11 : Colour mixing – definitions and misconceptions

- Chapter 12: The colour circle: Misunderstandings

- Chapter 13 : Finding a maximum of colours

- Chapter 14 – Colour mixing made easy

- Chapter 15 – Colour mixing by layering

- Chapter 16 – Reviewing previous chapters (1)

- Chapter 17 – Reviewing previous chapters (2)

- Chapter 18 – “All you need to know about painting”-2

- INTRODUCTION to Book 2 -“Painting with Colour”

- Chapter 19 – Colour and the feelings

- Chapter 20 – Optical mixing and its legacy

- Chapter 21 – Colour contrast effects

- Chapter 22 – Thin Lines

![]()

Thanks for these posts, Francis, coming thick and fast in the last week or so! It will take time to read and think about all the content.

Thanks for posting Francis. I’ve enjoyed reading your latest posts including this one. One of the aspects I’ve enjoyed most is seeing images of your work that illustrate the ideas so well. Of course, I realize, as you point out, work of this subtly isn’t best seen on a screen.

The discussion around the “integrity of the picture plane” is particularly important and insightful, because it identifies and explains the visual phenomenon that Mondrian, Pollock, and others talked about. So it seems that these artists gave different ‘esoteric’ names attempting to describe the same perceived space. Although much has been written about these artists and their ideas on space, to my knowledge, only you have actually drilled down and explained exactly what this visual phenomenon is and what causes it. This is a significant contribution to Art History.