Elizabeth Cavé and her great friend Eugene Delacroix

.

In an earlier Post I told of the teaching of Horace Lecoq Boisbaudran and its widespread influence. In it I did not mention another important figure who also developed a method for training the memory. Her name was Elizabeth Cavé. Like Lecoq Boisbaudran her method eventually found favour with the establishment and was to some extent introduced into the national curriculum. She was also, over some 30 years, a personal friend and confidant, often described as “mistress”, of Eugène Delacroix, who was something of a Father figure to the young Impressionists, including:

- Edouard Manet who appears in the “Homage to Delecroix”, the celebrated painting by Henri Fintin Latour, a student Lecoq Boisbaudran. Also included are two other students of his, Alphonse Legros and Felix Bracquemond

- Edgar Degas who, as a young man, went, with his friend Gustave Moreau (teacher of Matisse), to visit Delacroix in his studio. When they arrived, despite having been warned to expect a testy old cumudgeon, they were given a warm and generous welcome. In contrast they described his intellect “icy”, maybe a reaction to the scientific bent that led him to be an early champion of the ideas of Michel-Eugène Chevreul, the chemist who first enunciated the law of ‘simultaneous colour contrast’

- Probably all the other young ‘Impressionists’ for whom it is said that a ‘must see’ experience was the application of Chevreul’s law to be found in the frescoes painted by Delacroix towards his life (between 1857 and 1861), in the L’Eglise St. Sulpice, Paris.

.

My letter to LRB

With all this information in my head, you can imagine how my interest perked up when I came across a quotation from Delacroix in an article by T.J.Clark, published in the London Review of Books in October 2019. In this Delacroix tells us that he experienced a paradigm shift in his approach to painting, from being “hounded by a love of exactitude” to employing his memory to sift out “what is striking and poetic”. He also states that this transformation occurred as a spin-off from his “African voyage” in 1832.

On reading this endorsement of the virtues of channelling experience through memory, I was immediately reminded of the philosophy of Lecoq Boisbaudran. From there my mind jumped to Elizabeth Cavé and to wondering whether Delacroix’s change of direction had any link to her teaching method. When I discovered that their liaison had started in earnest in 1832, I could not resist the thought that either she had influenced Delacroix or, perhaps more likely, vice versa. If so, there seemed to be quite a lot to add to what T.J.Clark had to say. Below is what I wrote.

The letter

T.J.Clark (LRB 10-10-2019) quotes Eugene Delacroix as dating a change from being hounded by a love of exactitude to making work based on “recalling” what is striking and poetic. He asserted that it came after his “African voyage”, which mean after his return from Morocco in 1832. When I read this I immediately realised that this date roughly coincided with the beginning of his relationship with Elizabeth Cavé in 1833. Whether or not her ideas were influenced by Delacroix or visa versa , she published ‘Le dessin sans maître’, which received a laudatory review from her, by now long standing, friend (in the ‘Revue de deux Mondes’ of September 1850). In it, she explained her method of teaching drawing which, according to her, she had been practising since 1847. Key to this was training of the memory. Two years earlier, in 1848, Horace Lecoq Boisbaudran published a compilation of two texts, ‘L’Éducation de la mémoire pittoresque’ and ‘la formation de l’artiste’, in which he explained his method, also based on training the memory. His connection with Delacroix can be inferred from the personages in the 1864 painting ‘Homage à Delacroix’ by his pupil Henri Fantin-Latour, in which we see others two students of Lecoq Boisbaudran, Alphonse Legros and Felix Bracquemond. Also in the painting is James MacNeil Whistler who is know to have learnt Lecoq Boisbaudran’s method from Alphonse Legros and who famously demonstrated it to a doubter. He did this, first, by looking at an unfamiliar landscape and, then, turning his back on it and painting it from memory (for more about the influence of Lecoq Boisbaudran and its plausible ramifications see http://www.painting-school.com/horace-lecoq-boisbaudran-influence

So how does all this relate to the quotation from Delacroix? The clue lies in his youthful “love of exactitude” being replaced by a more mature approach based on “recalling what was striking and poetic.” What Lecoq Boisbaudran would surely have argued is that the great man’s earlier obsession with ‘accuracy’ prepared him for his later personalised use of memory with all its benefits, for this was exactly what his teaching method (and presumably that of Elizabeth Cave) aimed at achieving. The main differences, he could argue, lay in the shortness of the time in which his students were expected to make their transition and the methodical progression from simple to complicated that characterised the learning exercises that made it possible. Surely, both Delacroix and Lecoq Boisbaudran would have concurred with Edgar Degas, significantly a great friend of Alphonse Legros, when he said, “It is always very well to copy what you see, but much better to draw what only the memory sees. Then you get a transformation, in which imagination works hand in hand with the memory and you reproduce only what has particularly struck you.”

.

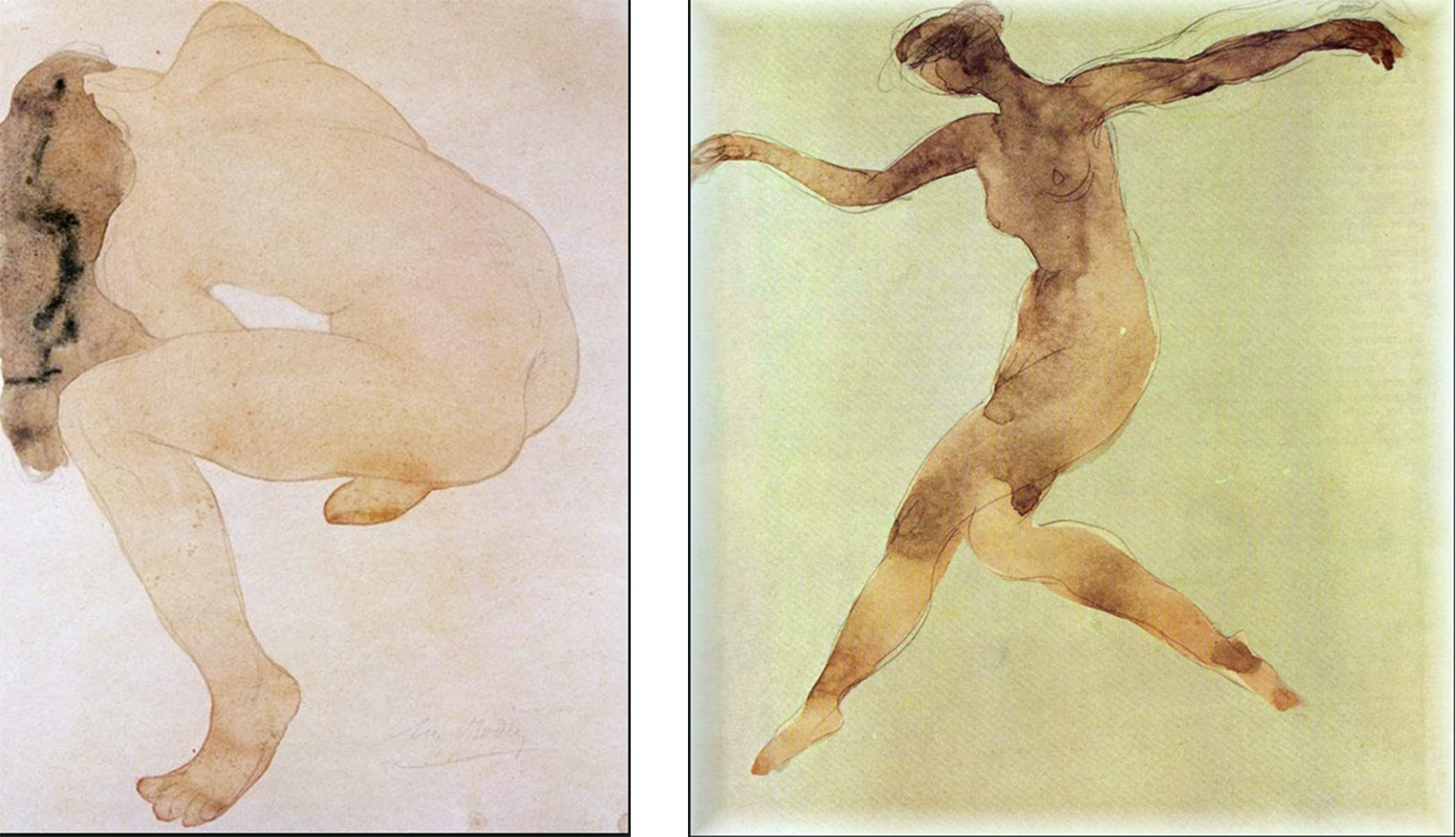

As well as the personalisation of artistic output, the method had huge advantages in terms of rapidity of information pick up. The famous late watercolours (‘Cambodian dancers’, etc) of Rodin, another student and a lifelong admirer of Lecoq Boisbaudran and his teaching, illustrate both these advantages. Likewise the post-African paintings and drawings of Delacroix. Also, I find it hard to believe that there is not some connection here with Delacroix’s famous assertion that “any artists worth his salt should be able to draw a man that has been thrown out of a sixth floor window before he hits the ground.”

PS. For your interest, I was teaching on much the same principles as Lecoq Boisbaudran for at leat 25 years before I learnt of his existence. These I derived from research done at the University of Stirling in the early 1980s <http://www.painting-school.com/the-course/the-course-director/>.

.

How interesting to learn about Elizabeth’s use of developing the memory when learning to draw. I had never even heard of her! I wonder who some of her students were. Thank you for continuing to expand this fascinating history of relationships and developments during this key time and place in art history.

Always enjoy your explorations into the imagination and science explord by the artists. Points to ponder!

Very interesting indeed!

Merci Francis de rechercher et souligner cette influence de grandes dames comme Elizabeth… en tout cas, elle était belle, muse sûrement …

It would be interesting to know more about Elisabeth Cavé and who her students were. Her ideas on memory were obviously being talked about even if the artists you mention didn’t all know each other.

Thanks Frances for this comment. You can access Elizabeth Cavé’s description of her method on the Internet. To my way of thinking it was not nearly as interesting as that of Horace Lecoq Boisbaudran. However, if for no other reason, the fact that Delacroix praised it and that it was taken up by the state, makes it significant in art history. All the male artists I mention did know each other and, in view of her relationship with their hero Delacroix, it would be astonishing if they did not know of Elizabeth Cavé and her interest in training the memory. All, except Delacroix, were either actual students of Lecoq Boisbaudran or friends of theirs who are known to have been enthused by his ideas.

Thank you, Francis. I read this with real appreciation and interest. I will share it.

Regards.