When I arrived at art school in the late 1960s, ambiguity was one of the first things we were expected to think about. Over the years I have learnt what an important role it has played in artist’s thinking over the last on hundred and fifty years.

Definition

Ambiguity occurs whenever two or more interpretations are in competition with one another. They may be within any domain of sensory experience or across domains, but here it is considered in relation to the visual domain. The purpose of this Post is to present some of the reasons why ambiguity should be of fundamental interest to artists, particularly if they are:

- Wish to depict illusory pictorial space.

- Seeking to create either harmony or discord in their paintings.

An illustration of ambiguity

.

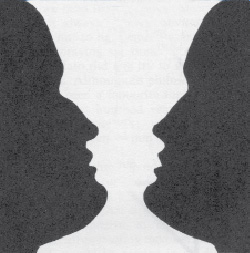

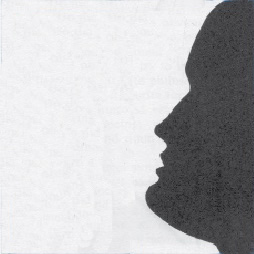

A good example of a high level of ambiguity is provided by the well known vase/face illusion illustrated in Figure 1, in which we can see either a vase or two silhouetted faces. However, it is important to notice that, although we can choose between the vase or the two faces interpretations, we cannot stop the ambiguity of the situation providing a degree of tension. The force of this can be sensed by comparing the right hand side face with the identical face in Figure 2 in which there is no left hand side face to create the vase shape. Clearly, by removing the ambiguity between the vase and the two faces interpretations, the face is easier to look at. The question for artists is whether they want to maximise ease of looking or to create works with some degree of tension.

.

Escaping ambiguity

As explained below, it can be argued that all paintings exhibit an ambiguity between their pictorial contents and their presence as objects with real surfaces. The the only way the escape this is to make use of one or more of the strategies that are available to us for that purpose. Not counting that of looking away altogether, these depend on concentrating attention on details at the expense of wider context, which can be done either by focusing down or by moving closer. However, although both these manoeuvres work well enough for reducing ambiguity in everyday visual perception, our eye/brains can seldom completely exclude the influence of alternative interpretations in paintings..

Real picture surface versus illusory pictorial space

.

One type of ambiguity has had a pivotal place in the history of painting. It is that between perceptions of an illusory pictorial space and awareness of the real picture surface. Historically speaking, it became important when the Impressionists and other early Modernist Painters were looking for ways in which their hand-painted images could combat the threat posed by the high levels of realism produced by the newly available photographic method. They feared that the fact that it was so easily and quickly obtained in photographs, would undermine their livelihood.

Luckily for them and for the history of painting, they saw photographic images as deceiving the eye and hit on the now seemingly absurd idea that this deception was morally reprehensible (an idea that was still influencing artists in the 1960s and beyond). Abruptly, for progressive painters at least, the trompe-l’oeil, which for so long had been the goal of artists, became something to be avoided at all costs.

The solution found by these Modernist painters was to introduce ambiguity. Their idea was to provide a counterpoint to perceptions of illusory pictorial space by emphasizing the reality of the picture surface. The painting, by Berth Morisot, illustrated in Figure 3, provides a good example of how brush marks and surface texture can be used as a means of preventing the trap of deception. What these pioneer artists reasoned was that the impossibility of being able to enter the illusory pictorial space created by the realism of the image without being aware of these indicators of real paint and real surface, meant that a salutary ambiguity would be inevitable. What they could not have guessed is that the wealth of unexplored possibilities that the picture surface/illusory pictorial space dichotomy would make available, not only to them but also to their successors during well over a century.

An example of competing cues

.

The Modernist Painters were also interested in another kind of ambiguity in which attention is drawn in competing directions. For example, Figure 4 shows Pierre Bonnard going a long way towards obscuring the features in his wife’s face, presumably with a view to allowing the telling gesture of the hand to take on more significance than it would have done had the eyes, nose and mouth been more clearly delineated. However, since this strategy completely fails to override the eye/brain’s built in tendency to give faces more importance than hands, the result is a pull in both directions. The consequent dynamic equilibrium is of central importance to the experience of looking at the drawing. Just as in Figure 1, it is difficult to look at the vase interpretation without being influenced by the two-face interpretation, it is difficult to look at either the hand or the face to the complete exclusion of the other.

Figurative versus abstract

.

Another area of competition is between pictorial dynamics based on figurative content and ones that involve non-figurative relationships such as those between colours, contours, textures, etc.. The more the Modernist Painters found their interest turning to the latter, the more they sought ways of playing down the influence of the former. A first step in this direction was that of reducing the strength of the cues that make recognition too easy (as in the case of the face in both the drawing of Marthe by Pierre Bonnard, illustrated in Figure 4, and the portrait of Ambrose Vollard by Pablo Picasso, illustrated in Figure 5). A second step was to get rid of figuration and its attention-distracting pull altogether.

Seeking to eradicate ambiguity

.

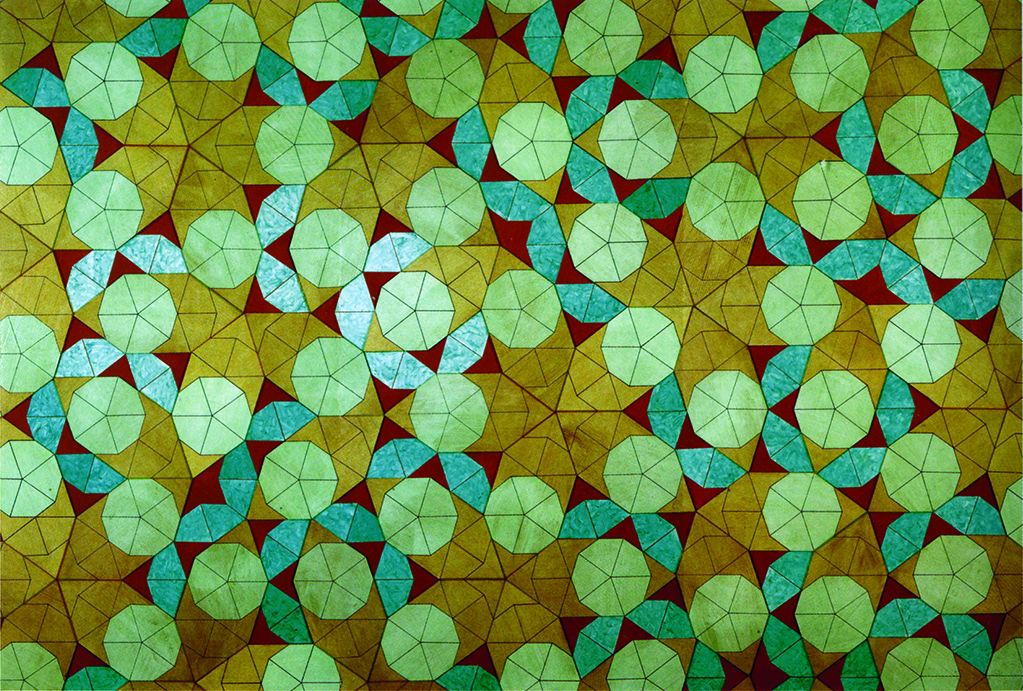

Many artists saw great potential in the removal of figuration but did not want to get rid of illusory pictorial space, which they felt gave extra dynamic possibilities to interactions of colour, contour, texture, in front/behind relations, etc. Others were still troubled by the immorality of deceiving the eye and sought to eliminate illusion altogether. They wanted all regions of their paintings to be perceived as being flat on the picture surface, as no doubt was the intention of Michael Kidner when making the work illustrated in Figure 6.

However, these purists were soon to realise that achieving this objective might prove more difficult than they had imagined. It seemed that no matter how hard they struggled, if a picture surface, had more than one region of colour on it, their eye/brains would find ways of creating perceptions of illusory pictorial space within it. In other words, they seemed unable to prevent some of the regions of colour appearing to be either in front of or behind others. Even the simplest two colour painting, such as the one by Ellsworth Kelly illustrated in Figure 7, would not do, for it gives at least some people the impression of a landmass, a horizon and a sky.

.

.

Sculpture?

.

In the end, the only solution seemed to be one colour paintings, of which many appeared in the 1950s and 1960s. These included the series of blue paintings, embarked upon by Yves Kline in 1957, and several works by Ellsworth Kelly on the lines of Figure 8. The only ambiguity remaining lay in the question whether these were correctly classified as “paintings”. Some might think it more appropriate to describe them as “sculptures” or, merely, as “objects hanging on a wall”. For those artists who identified (in my view falsely) the search to remove the ambiguity as being of the essence of “Modernism in Painting“, it was time for “Post Modernism“.

Harmony and discord

To find out what this has to do with “harmony and discord” please consult previously posted chapters from “Painting with Light and Colour” and excerpts from the “Glossary”. In particular I suggest reading:

Relevant chapter

Relevant excerpts from the Glossary

- What are colourists? (1): Some of the many meanings of the word

- What are colourists? (2): Difference between meaning of the word for Venetian Colourists and for Modernist Colourists?

- What does the word “colour” mean?

Another thought provoking article, thank you for posting it.

Thank you Francis…wonderful again!

Unlike much writing on art, this is clear and well presented. Thought-provoking too; I’m planing a continuation of my forest series of paintings, perhaps I’ll increase the difference between areas of surface texture and smaller realist areas, as with the Morisot illustrated. One of the main types of narrative ambiguity in the serise I’m working on is their geographic ambiguity- are my forests natural wilderness or planted forestry? You can see what I’m on about here http://www.markgibbs.co.uk/forest/ People don’t seem to feel comfortable until they know where these paintings are of… I don’t tell them!

Sorry I missed this. It seems I am not being regularly notified of incoming comments.

Thank you for your remarks. It helps to know that someone whose opinion I respect judges something I write to be “clear and well presented”.

I am pleased to find that you think of your forest paintings as a series representing a theme (incidentally, one which I find interesting). When I look back I realise that all my own paintings have been parts of series, each representing, consciously or unconsciously, what I have described to myself as ‘projects’, but which could be thought of as ‘themes’.

It all started with the question as to whether someone with so little demonstrated talent, could justify calling himself an artist. Not knowing any better, I set about seeing if I could master figurative drawing and painting (my first project). Luckily before I had time to be put off, either by my pathetic struggles or by the evident and continuing bewilderment of my friends, I met Professor Marian Bohusz-Szyszko, who provided me with a set of rules that he claimed represented “all you need to know about painting”. Not wanting to take such a breathtaking claim on trust, my next project was testing the extent of its validity. Doing so inspired my work as an artist for the next four years. Although I found that the rules that the Professor gave me transformed my paintings and to a large extent silenced my critiques, I found a deep flaw in their theoretical underpinning (which was later to inspire exciting scientific research). Also, I could not help noticing that few if any of the artists featuring in contemporary art magazines, and showing in the trend-setting London galleries were following them.

Fortunately my skeptical friends (now including a wife) changed the grounds of their attack. They now argued that if I were to call myself an artist, I should have a piece of paper to prove it. So it was with their enthusiastic backing I signed up for a degree-equivalent course in an art school. I went willingly because I hoped to find out more about contemporary art practice from a staff who were currently exemplifying it in their work.

So my next project was to make sense of what they taught. On the subject of colour it could hardly have been more different. Also, my tutors made me aware of a raft of painterly concerns that gave the lie to the exclusivity of the Professor’s claims for his simple rules. Of particular interest for me was the focus on the nature of creativity, one of the underpinning concerns of Modernist artists since the Impressionists. From then on, the search for a deeper understanding of what I learnt on this subject, particularly from the artist Michael Kidner, became an abiding theme of my thought processes.

To cut a long story short, the remainder of my artistic life, has been dedicated to proving to myself that the Professor’s rules can give an extra dimension of light, space and harmony to any painting whatsoever (the scientific research that I did with colleagues gave a convincing neurophysiological explanationsof why this is the case). It is only when these qualities of appearance are not considered to be desirable that they should be bypassed. My most recent projects have been “the Islamic Panel Paintings’, the ‘Breath Inks’ and ‘Breath Pastels”. The first of these used a simple motif, influenced by tile patterns found in Islamic temples, to give painterly expression to the creative possibilities opened up by my science inspired ideas. The ‘Breath Inks’ and ‘Breath Paintings’ were conceived as a way of bringing myself into harmony with context-driven processes of creativity analogous with those triggered by the ‘Big Bang’, the ultimate creative event, and its manifestations in the evolution of the species and the neurophysiological necessities that underpin visual perception.

Thank you for this post. I shared it.

Regards, Sylvia

Very interesting article. I’ve previously left a comment but I can’t see it here now.

So many different possibilities for ambiguity that eradicating it becomes incredibly difficult. It seems quite a blessing that painting and life are not so clear cut. Thanks for the post, Francis!

Some would say that it is impossible to eradicate ambiguity. Others would ask, “Why bother?”. In my view, the real question is whether the presence of ambiguity influences the experience of looking at the painting? Does it interfere with any aspect of what the artist is seeking to create? Or, does it act as a catalyst to new ways of seeing, feeling or thinking? The reason that Professor Bohusz-Szyszko tells us to avoid repetitions of colour is that he believes that they interfere with access to the latter. My research at the University of Stirling has explained that this is because the presence of two or more identical colours creates an insoluble classification problem for the eye/brain’s visual recognition systems. They are simultaneously informed that the repeated colour is both on the real surface of the painting and existing in illusory pictorial space.