The surprising eye

The eye is full of surprises. The biggest ones come from the structure of retina that is situated at the back of it. The purpose of this Post is to provide a link to images and explanatory captions that tell us more about this starting gate of visual processing. At first sight, much of what we find strikes us as bizarre. But, when we delve more deeply, we discover the considerable advantages of the way things actually are. It turns out that nothing would work nearly as well as it does, if things were arranged any differently. The images and their captions will go a long way towards explaining why.

In the process, they will help readers to get a better understanding of how the eye/brain combination makes practical use of the information contained in the ever-changing patterns of light coming into the eye.

The link to the diagrams

Click on the link below to access the images and captions referred to. They are extracted from ‘The Glossary‘ to the four volumes I am in the process of publishing on this website.

GLOSSARY DIAGRAMS (1)-THE EYE

![]()

What happens next

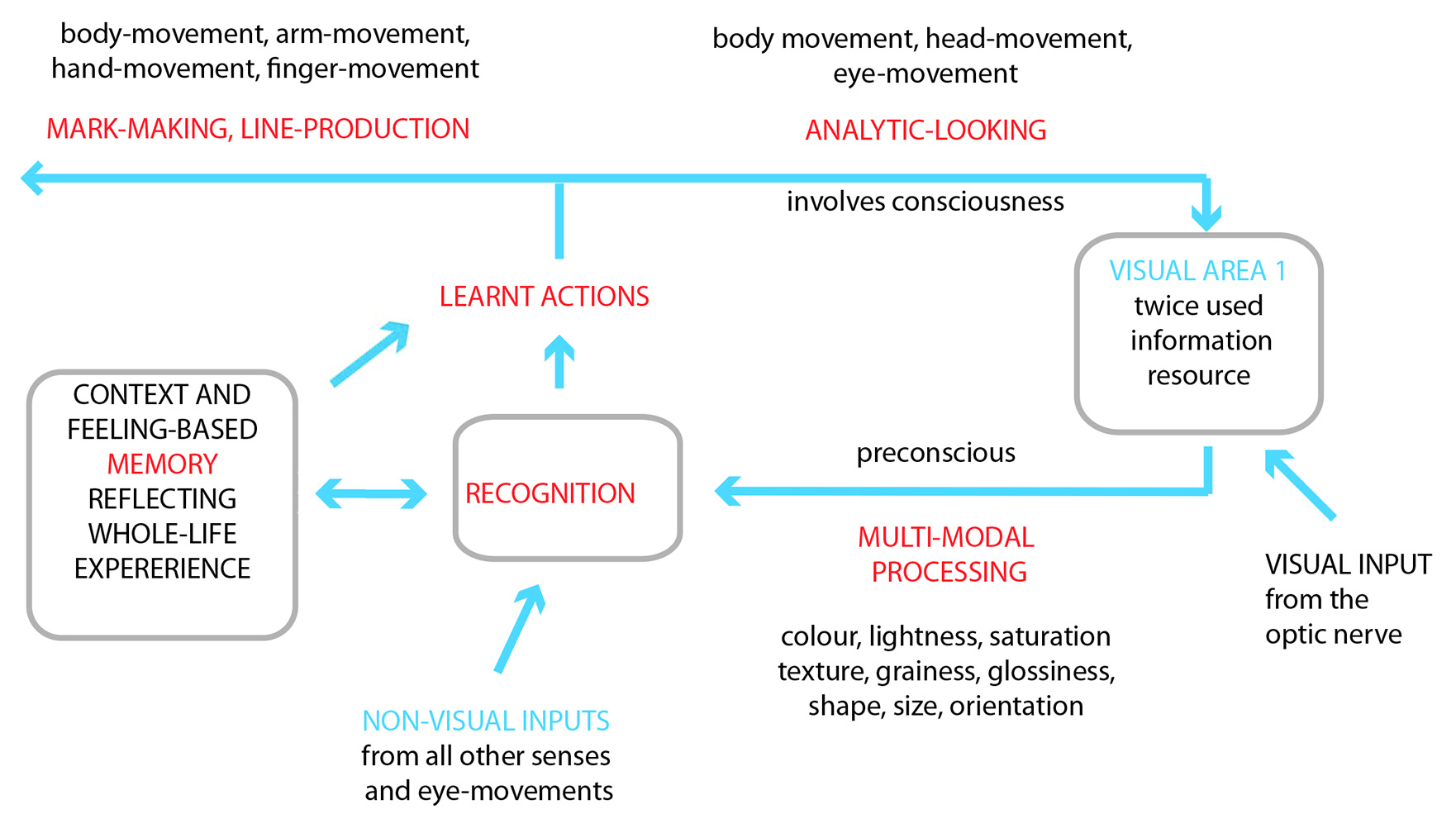

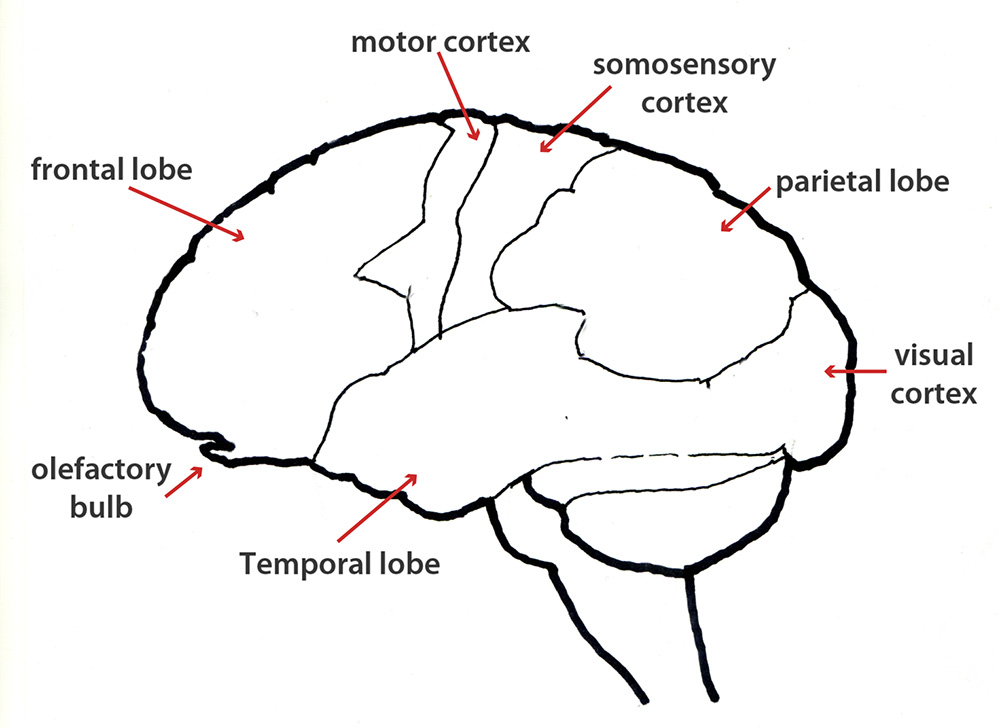

Upon leaving the retina, the neural signals travel in two directions. Some go up the optic nerve to the region of the neocortex known as ‘Visual Area 1′. Others take a completely different route that makes contact with the regions of the “Old Brain”. These play a central role in visual perception as we experience it. For example, they play their part in eye movements, spatial awareness, affective responses, multimodal processing, whole-field relations and much besides. Images and captions relating to both these routes will be posted later on this website, in a separate entry, entitled, “Visual Regions in the Brain”.

![]()

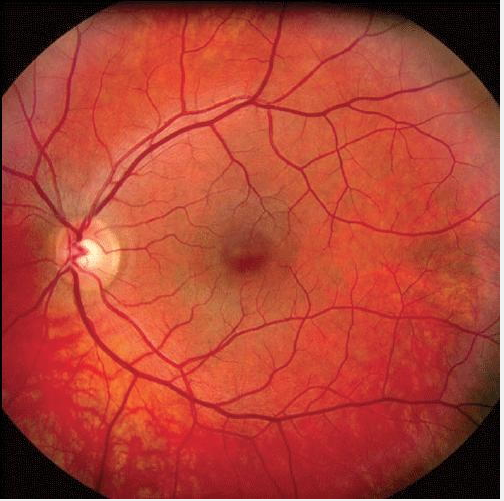

Images of blood vessels, neurons and and neural processes in the eye.

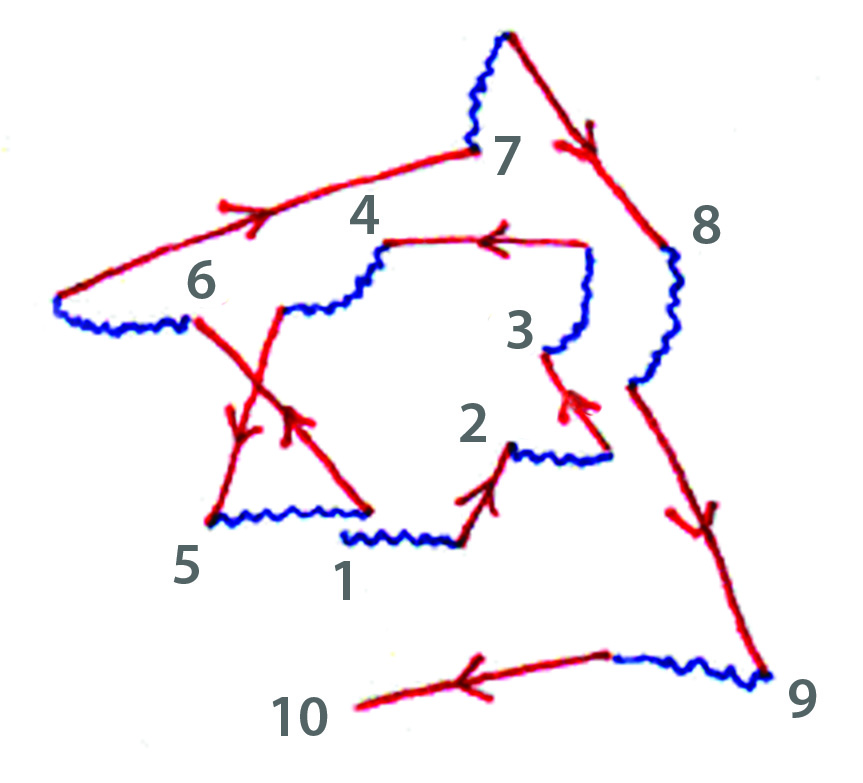

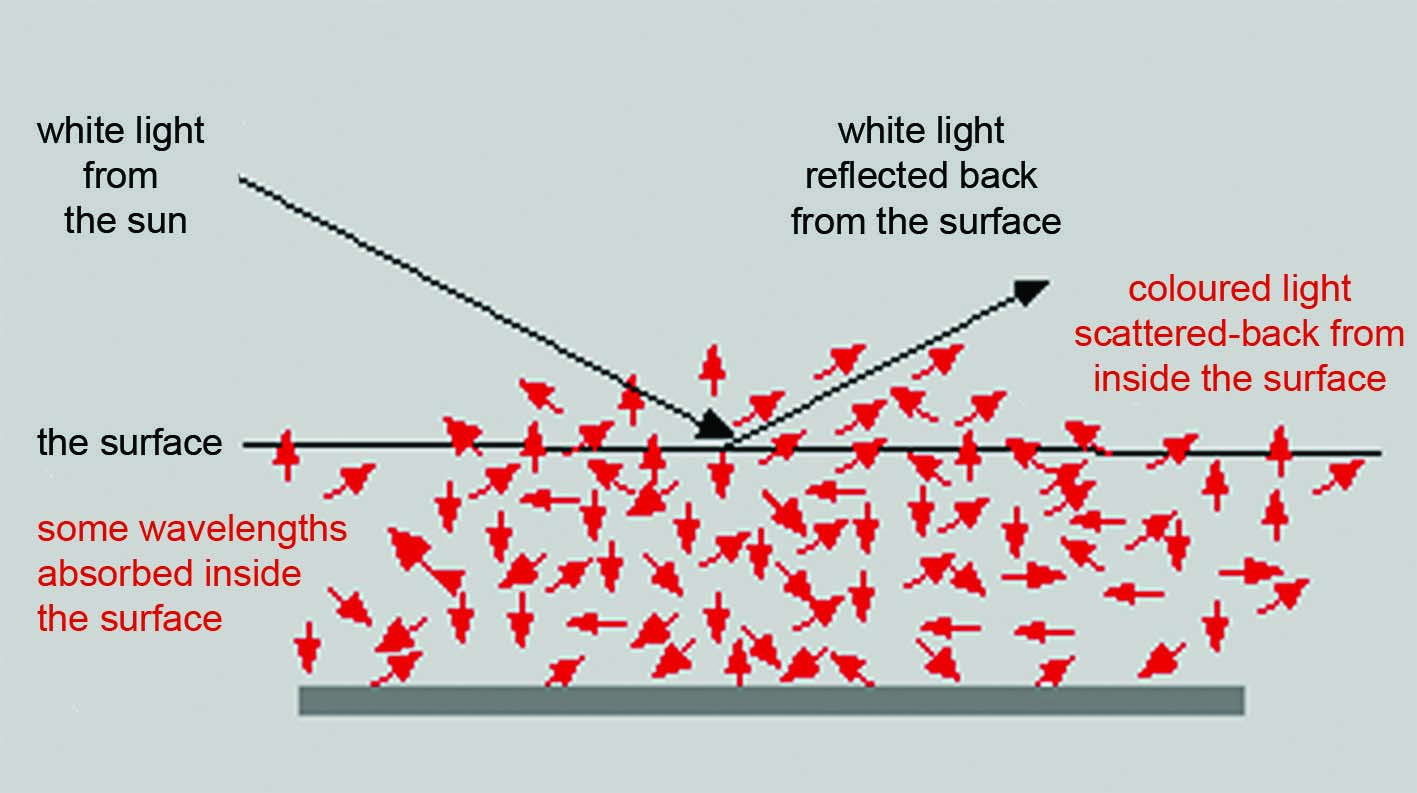

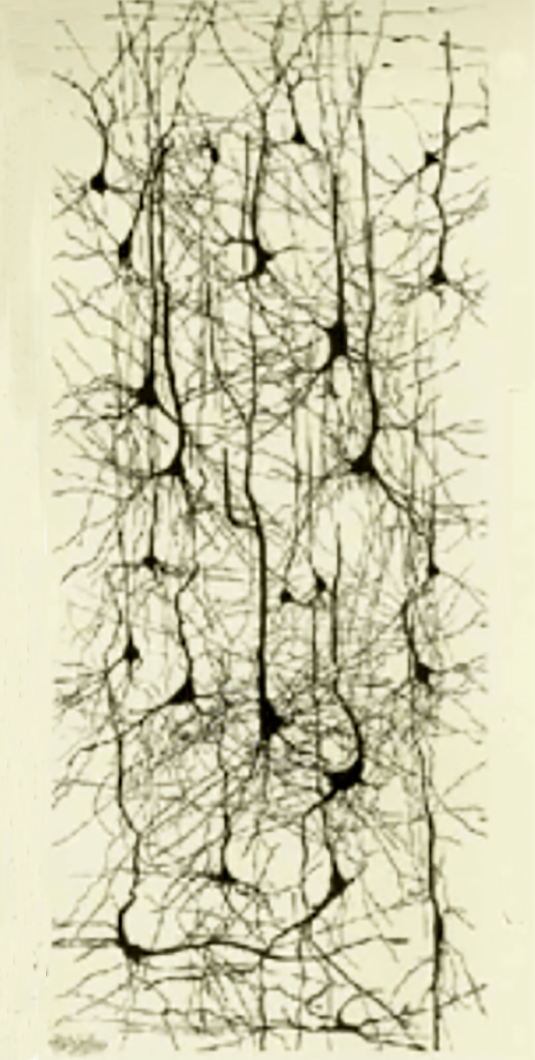

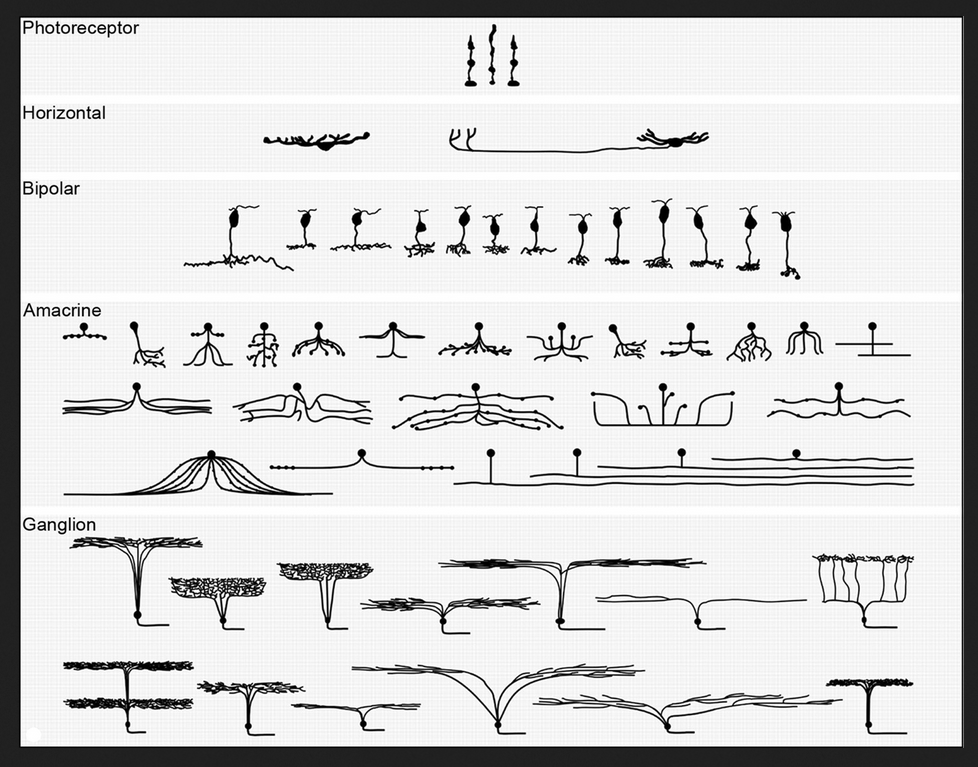

The human retina contains a very large number of neurons (cells) and a very much lager number of neural of processes providing links between them. It also features a dense network of blood vessels that supply blood to the neural processes. Together these three components make a significant barrier to the passage of any light that strikes the receptors. Until I learnt better, this light-blocking function did not seem to be of much of interest.

What changed my mind was the discovery that the light-sensitive cone and rod receptors that transform light-energy into neural signals, do not face towards the incoming light, but away from it. Consequently, the light coming into the eyes has to penetrate this light-impeding layer of neurons, neural processes and blood vessels, before it reaches the receptors. To add to my surprise, it turned out that the light-receiving end of the receptors is buried in a layer of dark matter. It was some time before I realised how these seemingly bizarre arrangements make possible visual perception as we know it.

The barrier confronting the light that enters the eye

It turns out that the barrier of neurons, neural processes and blood vessels compensates for the fact that the rod receptors are very much more sensitive to light than the cone receptors. The benefit of this state of affairs is that it enables a necessary degree of functional equality between the responses to the incoming light of the two different receptor-types. Needless to say, this equalling up would not take place, if the light striking the less sensitive cone receptors were to be subjected to the same impediments. This explains why the forces of evolution have created a gap in the neuron and blood vessel barrier in front of the region known as the fovea, exactly where the incoming light strikes the cone receptors.

Glare-blindness

If the equalling up process did not take place, the rod receptors would be bleached out whenever the incoming light was strong enough to activate the cone receptors. The result would be a massive degree of glare-blindness in daylight conditions.

Dire consequences

If they were effectively blind, the rod receptors would not be able to participate in daylight visual processing. As a consequence, the neural computations of whole-field relations could take place. One of the many aspects of visual processing that would rendered impossible would be the separation of reflect-light from body-colour. As a result there would be neither colour constancy, nor the use of the information residing in the reflected-light that has been separated out.

If this were so, pretty well all that I have written in my book “Painting with Light” would be nonsense.

Burying the receptors in dark matter

The burying of the light-sensitive receptor heads in the dark matter is easier to explain. It prevents the light from scattering from one receptor to the next and, consequently, reduces blurring.

![]()

Some numbers and sizes

One estimate for the number of the light-sensitive receptor cells is in the region of 150 million. Although the precise number of neurons and neural processes in the retina is unknown, it is certainly in the hundreds of millions. All this packs into an astonishingly thin layer (less than 0.5 mm) whose extent can be compared to that of a 10p piece.

A reference

If you want a comprehensive account of the component parts and structure of the retina, you could consult the relevant pages of the website of the The National Library of Medicine. You will find them dizzyingly more complex than the grossly oversimplified information given either above or in the ‘Glossary‘ extract.

![]()

Go to top of page

Go to list of all other contents

![]()