After posting thirty-seven of the chapters of my four books, I realise that I have missed out the “Introduction” to my two PART volume on drawing. In the edited extract from it below, some general remarks are followed by a brief focus on two issues of fundamental relevance to what follows. Also, as an extra bonus, I have added three images .

.

EDITED EXTRACT

GENERAL INTRODUCTION.

This volume differs in fundamental respects from earlier books on the same subjects. It offers new and practical guidance on drawing-from-observation. It does so whether the artist is seeking:

- Greater accuracy.

- More expressive power.

- Ways of speeding up without losing control.

Its starting point is an analysis of widely used artistic practices and teaching methods. The next step is to explain not only why these have both proved to be of lasting value but also why, as they are currently taught, they have significant limitations.

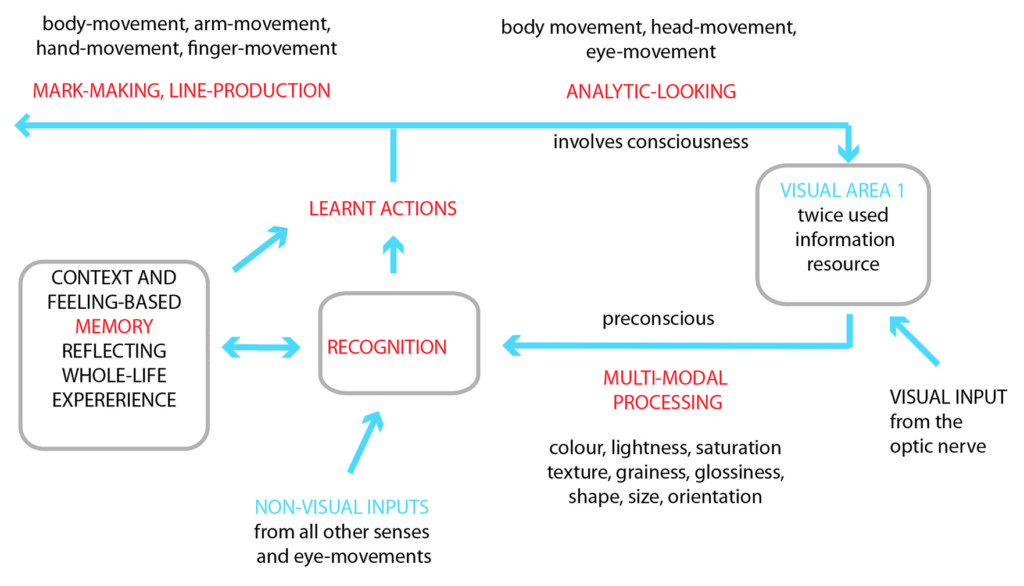

A main source of evidence for the proposals elaborated in the following pages is research, done by myself and colleagues at the University of Stirling in Scotland, into how artists use their eyes when drawing or painting. This forced me to a number of conclusions that differ fundamentally from those provided by other authors, including those promoted by Betty Edwards in her extremely popular book, “Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain”.

A similarity between Betty Edwards and myself is that both of us link our main explanations to contemporary science, with a special focus on neurophysiology. The difference is that the conclusions to which we come are radically different. While she relies heavily on a false theory of brain function, my arguments are are wider ranging, more up to date and demonstrably more relevant to drawing practice. As a result, I am able to offer a great deal of new and reassuring information on human visual capacities, clarify the nature of the obstacles facing all who engage in drawing from observation and indicate effective ways of circumventing them.

During my 30 years teaching at the Painting School of Montmiral, I have had the opportunity of testing the research-based ideas on hundreds of students of all levels of attainment and a wide variety of aspirations. Although the outcome is clear and encouraging, a word of warning is appropriate. Both experience and theory make it clear that, while early progress will almost always be rapid, both for beginners and experienced artists, there is no escaping the fact that, as with all skills, the highest levels of attainment require a longer term commitment.

Experience and theory also show why early difficulties seem more daunting to some people than for others. Should this turn out to be your case, there is no need to be discouraged. No matter what your starting level, you can have confidence that, if you have the motivation to persevere, the new ways of looking and doing that I advocate will help you to far exceed your expectations.

.

THE SCIENTIFIC PERSPECTIVE

.

.

My experience as a teacher makes clear that everyone has difficulties with the accurate depiction of the outlines of objects. My research at the University of Stirling helps us understand why. It also sets us on the way to achieving the combination of accuracy, speed and expressive power mentioned above.le of

As the science upon which much of my teaching depends will be unfamiliar to readers, a few words on two key ideas are appropriate. These centre on the subjects of “the variability of appearances” and “recognition”.

Variability

A useful preparation for understanding the nature of the problem with which variability confronts us, is the realisation that no two objects or parts of objects ever present the eyes with the same outline, even ones that are classified as the same object-type. Indeed, because appearances are altered by every change in viewing angle and/or viewing distance, even the same object (unless it is a sphere) will never be identical in shape unless viewed from exactly the same position. Each set of relationships, whether between different sections of contour or regions colour will always be unique.

This fundamental truth of visual perception brings us to an extremely important implication of this unvarying rule of variability and the consequent uniqueness of all perceived objects. It is that, since, by definition, recognition depends on seeing something as being the same on different occasions, the precise characteristics of the contours artists seek to represent can only have a supplementary role in the processes that enable it. Accordingly recognition must regularly involve overlooking the details of shape in favour of more general information. As we shall see in the following pages, the extent of overlooking can be huge.

.

Recognition

Below are links to chapters from my volumes on drawing:

VOLUME ONE : “DRAWING ON BOTH SIDES OF THE BRAIN”

BOOK 1 : “DRAWING WITH FEELING”

The chapters so far loaded:

-

- Introduction to book 1 of “Drawing with Feeling”

- Chapter 1: Accuracy versus expression

- Chapter 2: Traditional artistic practices

- Chapter 3: Modernist ideas that fed into new teaching methods

- Chapter 4: the sketch and explaining the feel-system

- Chapter 5: Negative spaces

- Chapter 6: Contour drawing

- Chapter 7: Copying Photographs

- Chapter 8: Movement, speed & memory

- Chapter 9: The drawing lesson- preparation

BOOK 2 : “DRAWING WITH KNOWLEDGE”

The chapters so far loaded:

OTHER POSTS ON DRAWING: