Illusion in painting

Over the centuries, at least since the Italian Renaissance, artists have sought to represent three dimensional objects and scenes on two dimensional surfaces. By implication, this required them to create an eye-deceiving third dimension (‘trompe-l’œil‘).

To achieve their objective, they and their successors: (a) mastered the laws of ‘linear perspective’, (b) delved deeply into the subject of ‘anatomy’, (c) explored the form-making properties of ‘gradation’, (d) recognised the importance of ‘overlap’, (e) provided explanations for the phenomenon of ‘aerial perspective’, (f) explored whole-field lightness relations (‘chiaroscuro’) and (g) demonstrated the value of existing knowledge of the form of objects and the layout of scenes in influencing how viewers would perceive them (‘cognitive cues‘). In other words, over the centuries the artists have pioneered our understanding of just about everything that psychologists of perception needs to know about illusory pictorial space.

However, there was one big absence and it is this that dominates the discussion of illusory pictorial space in two of my books. In “Painting with Light and Colour” the subject is approached from the perspective of artistic practice. In “What Scientists can Learn from Artists”, which contains the chapter that can be obtained by clicking on the link below, its treatment has both scientists and artists in mind.

The chapter also touches briefly on the issue of what they saw as the immorality of deceiving the eye, which was to have both a decisive and long lasting effect on the evolution of painting from the Impressionists until the late 1960s at least. More on this in my other books.

.

CHAPTER 6-ILLUSORY PICTORIAL SPACE

.

A pictorial history of illusory pictorial space

————————-

.

Other Chapters from “What Scientists can Learn from Artists”

These deal in greater depth with subjects that feature in the other volumes

- Introducing the chapters

- Chapter 6 : illusory pictorial space

- Chapter 8 – Constraint in artistic aids and practices

- Chapter 9 – Blindsight & the bakery facade

- Chapter 10 – Movement, surface-form and spatial layout

- Chapter 11 – Body colour and local colour interactions

- Chapter 12 – Colour constancy

- Chapter 15 – The other constancies

Terrific. Thank you.

Thanks, Sylvia, Its good to know that what I write is being appreciated.

I always enjoy your posts and find the information helpful and mind expanding. It’s fun to try and integrate new ideas into my own paintings. I look forward to the next one and reading more of the chapters of your book. Carol

Hello Carol. Although I am very happy to learn that you find my Post “helpful and mind expanding”, what pleases me even more is that you are investigating ways of integrating into your own work the ideas you find in them, as well as in the chapters to which they link. Comments like this make me feel that all the work involved in developing the ideas, writing the books and introducing people to chapters has been worthwhile.

Fascinating and informative, well-illustrated too. The flattening of pictorial space by modernist painters is probably not a new discussion but what is new, is the deep scientific-phycological understanding of how and why the eye-brain interprets visual cues in certain ways. This I haven’t come across anywhere except at Montmiral. Why such vital information isn’t widely appreciated by painters and drawers is strange. This is such important information. For me your 2 rules for realism 1] all colours should have some complimentary in, and no colour should be exactly repeated is the heart of the teaching at Montmiral. I was particularly interested to be reminded that all this is true for ‘monochrome’ drawing too, explaining how difficult it can be to create believable space in a drawing. At present, I’ve been working on a series of drawings exploring natural and military camouflage patterns, [real space vs illusory space designed to work against each other], and running into the problems described in the chapter; ie with a limited number of pencil greys it’s hard not to repeat colours. Thanks for posting and best wishes

Thanks for this Mark. There are various reasons why the information isn’t made widely available. Two of them are: 1) because other people do not seem to have had the luck to be put in a position to rescue so much of it from the the dustbin of history, (2) because other people have not had the additional luck of being put in position that favoured the doing of the relevant scientific research. A third reason is that, because I have had such difficulty in writing everything up to my satisfaction in book form, it is only recently that I have felt myself to be in a position to publish it. A fourth reason is that I have no idea how to get it published in a form that would catch the attention of relevant people.

As for the issue of creating variations of lightness in drawings, the solution lies in the fact that the relevant visual systems pick up information from regions rather than points. This means it can compute the average lightness of a region, a fact that means differences in lightness can be obtained by using variations in texture. Try making a grid of vertical and horizontal lines, then fill in the gaps between them with other vertical and horizontal lines. The result will be change in average lightness. Now draw more vertical and horizontal lines in the remaining spaces or draw a grid of diagonal lines across the original grid. The result will always be a change in average lightness to which they/brain visual systems are sensitive. The lightness level could also be controlled by covering a surface with dots and then putting other dots in the gaps between them and then more dots, etc.. Indeed any way of varying texture will do. In any of these situations you could also another dimension to the extent of lightness variation by making the lines or dots (or some proportion of them) darker or lighter. It is hard to get much more than ten or so variations in this way, but, as you will appreciate, when these are integrated into the texture variations, enormous number of lightness differences can be obtained. You could get an idea of how many by looking at some of the charcoal drawings of Sarah Elliott <https://www.sarahelliottstudio.com/> . I cannot imagine you will find better examples. See if you can find any repeats (unfortunately the fact that you will see the images on a computer screen may invalidate this exercise)..

Hello again Mark, in addition to what I wrote above, perhaps you might like glance at (and comment on please): http://www.painting-school.com/why-read-my-science-book/. I will shortly be publishing a more substantial introductory piece.

Hello Francis, thanks for your very helpful advice about drawing, which I’ll definitely explore. Also the link to Sarah’s website- I see the relevance of your comments on drawing especially with her charcoal drawings. I’m sure there are lots of other connections too, which will reveal themselves when I’ve more time to study her images. I look forward to reading your other posts.

I hear what you say about the many challenges of getting this information a wide audience. My comment on that score wasn’t a criticism of your efforts, quite the reverse. [I don’t think you took it that way, but just to be clear!] The more I read your posts the more I’m critical of much of the other art education and academic practice I come into contact with. For example, there seems to be a convergence of art degree courses; huge effort is put into exploring the connections between art practice and philosophical text, art and symbol, art and word-meaning, and many other subjects [which is all fine] but as far as I can see there’s very little time and esteem given to understanding visual perception and how that impacts on artists’ depiction of the visual world. Thanks for your posts- keep on with the grand project.

Very interesting – thanks for providing the illustrations

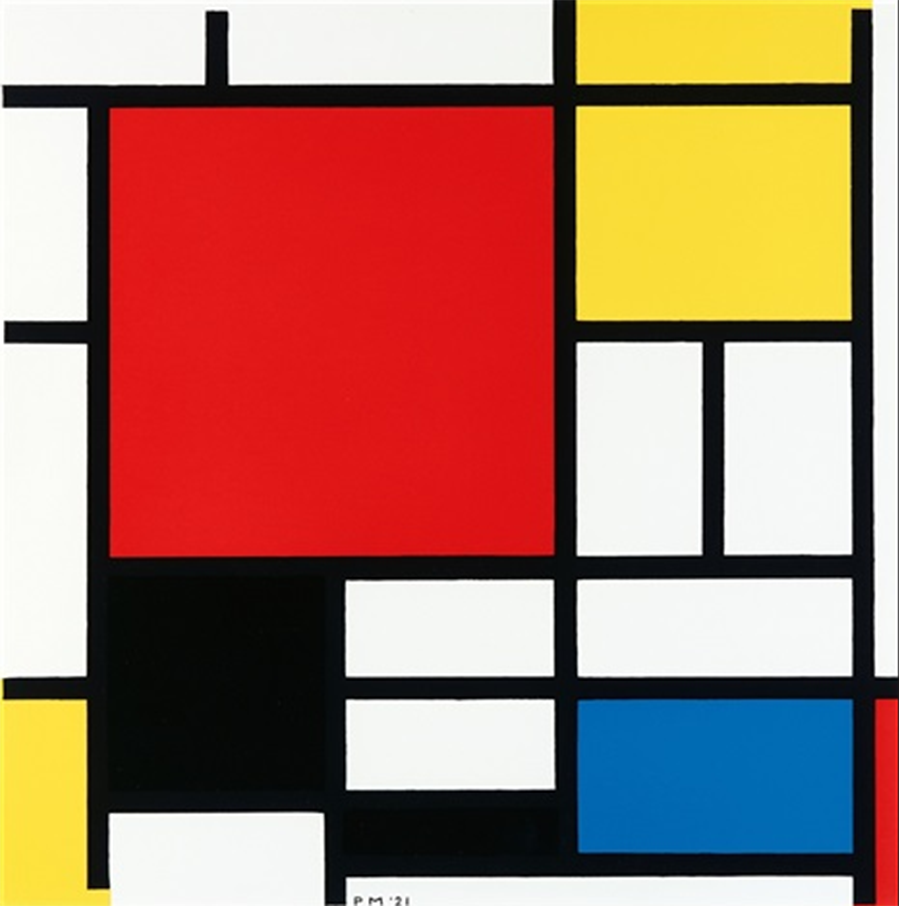

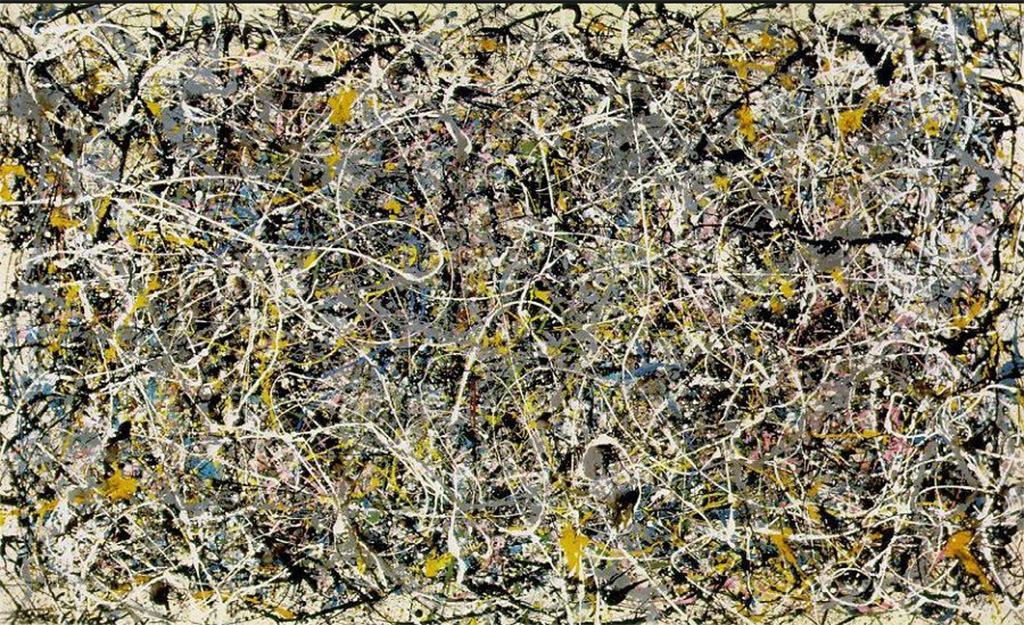

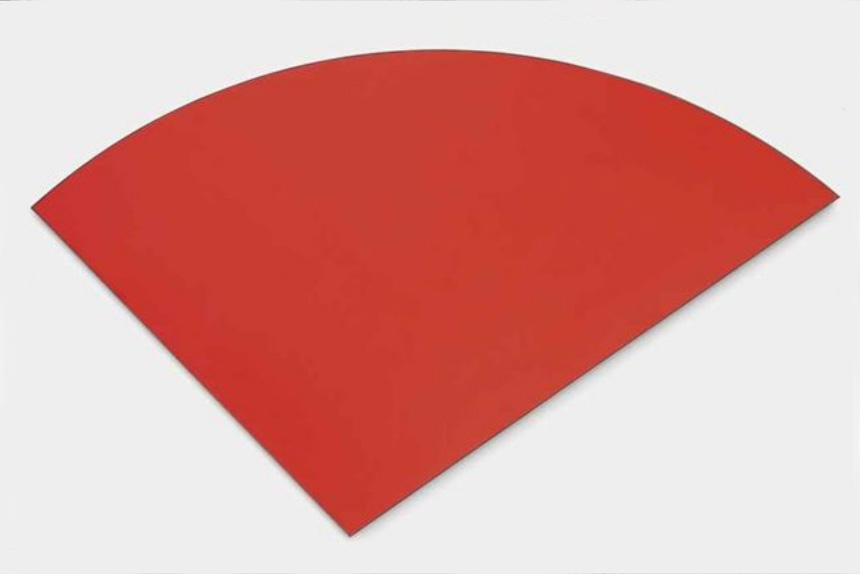

Thank you Francis..the images clearly exemplify some of the movements in painting regarding illusory pictorial space. It is a fascinating story!