.

.

Horace Lecoq Boisbaudran came to my notice in 2014. In later posts I will be saying more about him. In brief, I was amazed and gratified to find that the research upon which he based his teaching has more in common with my research than anything else I have come across. Although the exercises he proposed differed in many details from the ones that I suggest in my books, we have in common the idea that training the memory requires rigorous exploration of the unvarying uniqueness in the appearance of every object. Horace Lecoq de Boisbaudran’s pupil Alphonse Legros, who actively promoted his teacher’s ideas, became a close friend of Edgar Degas. It may therefore be no coincidence that it was he who provided the best synthesis of Horace Lecoq Boisbaudran’s philosophy that I know:

“It is all very well to copy what you see; it is much better to draw what you only see in memory. There is a transformation during which the imagination works in conjunction with the memory. You only put down what made an impression on you, that is to say the essential. Then your memory and your invention are freed from the dominating influence of nature. That is why pictures made by a man with a trained memory, who knows thoroughly both the masters and his own craft, are almost always remarkable works; for instance Delacroix.

Where my teaching is substantially different from that of Horace Lecoq Boisbaudran is the emphasis I put on training the “feel system“.

Meanwhile here is an extract from the “Glossary” to “Drawing on Both Sides of the Brain” that provides an introduction to his ideas and his influence. I have also added the entry for Alphonse Legros, described as his star pupil, who had great success in spreading his ideas to both his own generation and the following ones.

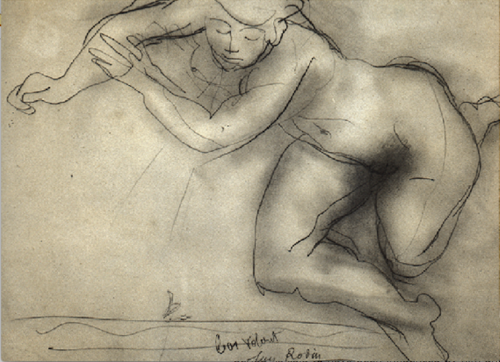

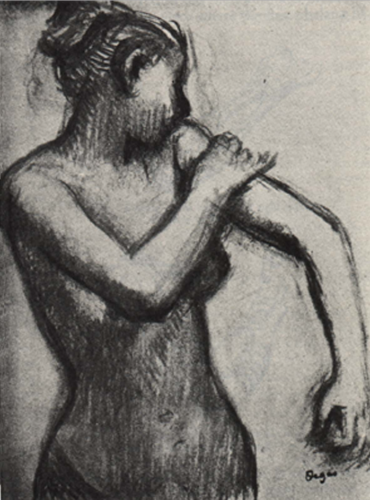

Lecoq Boisbaudran : Horace Lecoq Boisbaudran (1802-1897) taught drawing in “l’École spéciale de dessin et de mathématiques”, commonly referred to as the “Petite École” and now known as the “École nationale supérieure des arts décoratifs”. He was the author of “The Training of the Memory in Art” and “the Education of the Artist”, first published in 1847. His influence amongst artists of his time was profound and extensive. His students included (a) Auguste Rodin, (one of whose rapid drawings appears in Figure 1, Chapter 6 of “Drawing on Both Sides of the Brain”), (b) Jules Chéret, the prolific maker of posters, which are notable for the seeming freedom of the mark-making, (c) Henri Fantin-Latour, who was a friend of Manet and the Impressionists, (d) Eugene Carrière, a close friend of Rodin, who was much admired by many of his contemporaries, including the Impressionists and Picasso (whose “blue period“ is said to have been influenced by him and who drew a great deal from memory), (e) Felix & Marie Bracquemond, who mixed with progressive artists including Delacroix and the early Impressionists (Marie Bracquemond treated Claude Monet and Edgar Degas as mentors), (f) Jean Baptiste Carpeaux who exchanged letters with Degas and (f) Alphonse Legros (see below) whose friends included: Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas, who greatly admired his drawings, as well as Fantin-Latour and Camille Pissarro. He also influenced James McNeil Whistler, who publicly demonstrated the efficacy of the Lecoq Boisbaudran method by painting a never before seen landscape from memory. Legros, also taught John Peter Russell, who had close links with Vincent Van Gogh, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, Emile Bernard, Paul Gauguin, Claude Monet, Henri Matisse and others. Also Pablo Picasso is known for his reliance on drawing from memory.

Lecoq Boisbaudran developed a method of training memory that had much in common with the “Feeling Based Drawing Lesson” described in Chapters 9-11. His students were required to copy progressively complex shapes (starting with straight lines and rectangles) and objects before drawing them from memory. The outcomes were then subjected to rigorous comparison with the model and mistakes corrected, over and over again if necessary. Eventually, the students graduated to making careful analyses of masterworks in the Louvre and then drawing them from memory when back in the studio. The examples shown at the back of Lecoq Boisbaudran’s book show they were able to do amazingly well.

The extremely high level of rigour Lecoq Boisbaudran required from his students when drawing from observation was legendary. He argued that absolute accuracy was necessary if the full uniqueness of the model were to be revealed, and claimed that it provided the best way of extending the scope of long term memory. In both cases he was certainly right, for all overlooked features would have to be filled in the basis of previously existing and therefore inappropriate memories: the essence of intellectual realism and academicism. As explained in “Drawing on Both Sides of the Brain”, Chapter 8, the steps required to achieve rigorous accuracy, not only stock the memory of the artist with a great deal of new information about what he or she is looking at, but also prepare the way for more rapid information pickup. But, perhaps the most important of all, it enriches the memory store which is the source of the imagination.

The most important difference between the memory training method promoted in my book and that of Lecoq Boisbaudran is that he advocated the use of a technique known as “marking”. This involves hovering the tip drawing instrument over the approximate end point of stretches of contour being analysed, as a means of establishing its precise position and, then, marking it with a dot. Although this is a very efficient way of ensuring accuracy, it does so in a way that distances the artist from his or her feelings. In contrast, my “Feeling Based Drawing Lesson” concentrates on training the ability of the feel system to make accurate estimates of relativities.

Legros: Alphonse Legros (1837 – 1911) was a star pupil of Horace Lecoq Boisbaudran and an important conduit of his ideas about training the memory. He and his fellow pupils, including Henri Fantin-Latour and Auguste Rodin passed them on to their friends James McNeil Whistler, Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas Legros was later to become Professor at the Slade School of Fine Art in London. One of his pupils during his tenure was John Peter Russell, who was later to join Vincent Van Gogh, Emile Bernard and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec in the studio of Fernand Cormon in Paris.

Francis Pratt 2016

Fascinating!

Francis, I’m really hoping to be able to sign up to a life drawing course with you and put some of this into practice.

Francis you are up there with stellar instructors: an unforgettable experience. Thank you, from a veteran student

Absolutely agree!

Quite interesting, Francis. I may try and locate Boisbaudran’s text myself since I’ve recently read a couple essays by Louis Finkelstein and Mercedes Matter regarding ‘the education of the artist.’ As a former educator myself (professional writing), I’m interested in the ways that writing about the art one creates can impact one’s artistic thinking and production. Cheers!

très intéressant, je ne connaissais pas ce maitre, professeur de dessin

Thank you for this very interesting article and your clear explanation. I didn’t know about Lecoq Boisbaudran; the links between all these different artists are fascinating, I’ve got much to learn and discover.

Drawing is not what one sees but what one can make others see. Edgar Degas.

Thanks for this reminder that Degas, friend of Alphonse Legros, was a master of thought-provoking sayings. Here are some other examples:

A first, which fits well with Lecoq Boisbaudran’s ideas on the transformative power of the memory: “it is always very well to copy what you see, but much better to draw what only the memory sees. Then you get a transformation, in which imagination works hand in hand with the memory and you reproduce only what has particularly struck you.”

A second, which questions what he might mean by the word “see”: “For myself, I am convinced that these differences of vision are of no importance. One sees how one sees. It is false but it is this falsity which constitutes art.”

And a third, which seems to define drawing differently: “Drawing is not shapes, it is one’s feelings.”

All four are well worth pondering

Oh yes, well worth pondering! I especially love the second one!

Rather be doing than reading, but this is important and I hope useful when I get pencil and brush in hand. Wishing I could be in the studio in Montmiral once again. Too far away in Cambridge mass, thank you C

Francis, thank you so much for these posts, and for the student comments. Like Catherine, I feel too far away now, and these posts and comments help me feel part of wonderful, enriching, ongoing conversations on art that inform and expand my personal study with you, and with your three brilliant, generous resident artists. Their work, each so different and so vibrant, deepen my appreciation of your work and teaching. They inspire me. Their work, so humbly approached each day, give me additional courage to stand in your impressive and supportive presence and paint. Thank you for everything. How did I get so lucky to find you? My dear friend, Frances Meadows found you for me, and shared her impressive paintings and drawings from her various sessions with you. So, with ongoing admiration and real affection, thank you!

Illuminating as well as educational. Thank you!

I am reminded to make more time for drawing, it’s pleasures and repercussions, thank you Francis.

Francis, at your suggestion, as part of another conversation we are carrying on about drawing and drawing methodology, I came back to this article. This reading, in light of subsequent learning, is deeply insightful and helpful. Thank you for referring me back to it. Very valuable.

Sylvia

Hi Francis, I know I’ve commented on this page before. But the page is especially significant as we discuss the wonderful watercolors of James Whistler, currently on view at the Sackler Freer. I’ve been back to see them several times. Watercolor is my favorite medium, but rarely have I been so gratified from closely repeated viewings of a single exhibition. With each viewing, each painting in the exhibition seems fresh and surprising and new. Thank you for helping me understand many of the reasons why.