Is constraint necessary for creativity?

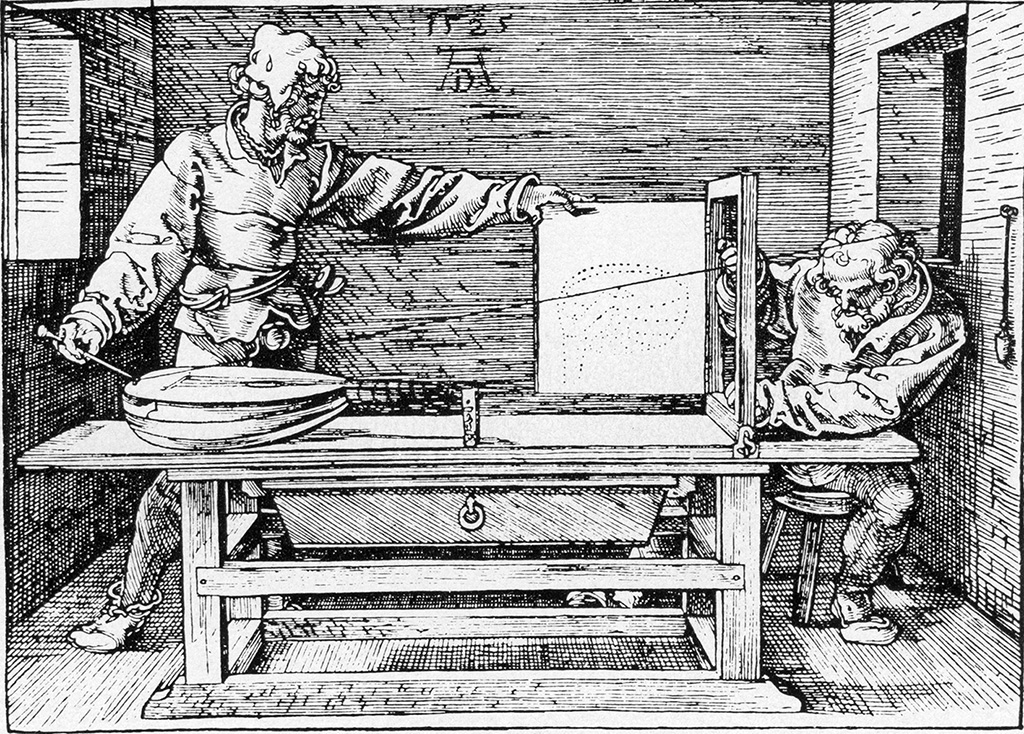

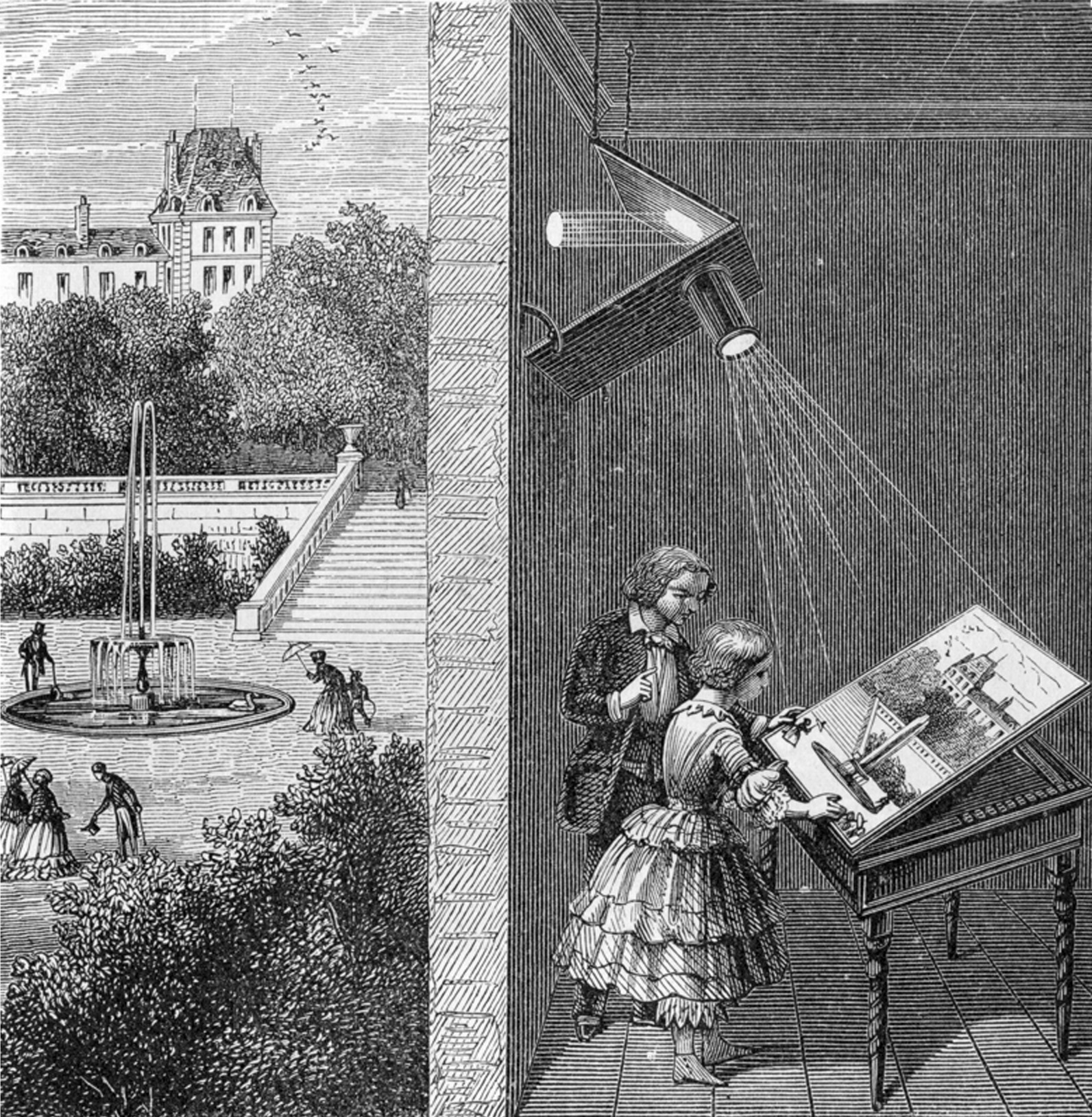

The purpose this Post is to provide a link to “Constraint in artistic aids and practices “, Chapter 9 in my book “What Scientists can Learn from Artists”. As in several other Posts that publish book chapters, I include a slightly edited reprise of its“introductory”, in the hope it will whet your appetite and encourage you to click on the link below. I am hoping that when you have read all the chapters of all my books, you will realise that the answer to the question posed in the heading to this section is “Yes”. The images below illustrate two methods of constraint favoured by artists in former centuries that foreshadow ones that are widely used today: For example, photographs, slide projections, and computer controlled images. All of these, whether consciously or not, make use of constraints, the possibilities of which have been developed by evolution over the millennia, such as standing still, choosing a viewing distance or closing an eye al of which constrain input to our visual systems and, thereby, enable learning and creativity, its corollary.

.

.

.

Introductory

If we want to be creative, we will have to free ourselves from the constraints of old ways of doing things in order to go beyond them into new territory.

In this chapter, we take a step towards the goal of a practical understanding of how this might be done. It starts with my telling how I stumbled on the intuition that constraint may be a necessary condition for exploring the unknown, and provides examples of how the community of artists, whether consciously or not, have made much use of this possibility. Eventually I found myself coming to the seemingly paradoxical conclusion that constraint is necessary if we are to achieve either meaningful freedom or creative self expression. I also came to realise that the use of constraint is one of the guiding principles of our evolution as a species.

My approach to going deeper into the creative powers of constraint, starts with account of how I came to realise their central importance. I use the particularities of my own story because of the insights it furnishes relating to the creative process in general: long periods of gathering data, struggles with the confusion that they seem to engender, a sudden intuition that provides a lead on how order might be found and, finally, doing the work necessary to test its validity.

The inspiration for my breakthrough came when reading a book by J.J. Gibson, one of the most controversial yet influential perceptual psychologists of the day.

.

CHAPTER 9-CONSTRAINT IN ARTISTIC PRACTICES

.

Other chapters from “What Scientists can Learn from Artists”

These deal in greater depth with subjects that feature in the other volumes

- Chapter 10 – Blindsight and the bakery facade

- Chapter 11 – Movement, surface form and spatial layout

- Chapter 12 – Body colour and local colour interactions

- Chapter 13 – Colour Constancy

- Chapter 15 – The other constancies

.

Go to list of all other contents

Thanks for this Francis. I’m hoping to come back to the chapter referenced, when time allows.

all seems to me very clear … always learn from new reading Francis !

Hello, Francis! I read Chapter 8 and found it quite interesting. Although I have not read Gibson’s book, I do have a couple comments that relate to your discoveries.

If I understand the point of this chapter, it is to amend Gibson’s critique of laboratory experiments as not being useful due to the variety of circumstantial / contextual elements absent from the real-world situation of an activity. To state it differently, it seems Gibson is drawing a distinction between the laboratory experiment and the actual study of a person doing something in situ, or in the context in which that activity normally occurs.

Although you offer some useful ideas with respect to Gibson’s thesis, particularly your parallel of the perspective frame with what may occur in a laboratory experiment studying vision, for example, I believe you are conflating the notion of activity with that of tool use. Gibson is critiquing activity: the artificial (laboratory) vs. real-world. You are discussing tool use within real-world activities. The artist creates using a variety of tools, as you rightly note. However, to my knowledge there is not an artificial environment in which the artist creates. He may use a sketch as a preparatory tool to better understand / approach a final painting but the sketch is still made under “normal” circumstances. Or, she may use a picture frame to map out the sections of a drawing, but the drawing itself is still being made in a real-time, real-world situation. This is rather different than Gibson’s distinction between the laboratory and actual practice, is it not? I’m having trouble following your reasoning based on this distinction.

Thanks for considering my proposition.