A quotation from Antonio Tapies

In an earlier Post I suggested the advantages of a games-playing attitude as a stimulus to creativity. Due in large part to his pioneering explorations of picture-surface characteristics as subject matter for painting, Antonio Tapies came to be regarded by many as one of the key figures of twentieth century art. He has also proved himself a stimulating writer. One of his literary productions is a very brief essay entitled, “The game of knowing how to look”, in which he gives his advice on creative looking. He starts by advocating focusing attention on some simple object, such as an old chair. He elaborates:

“It hardly seems worth looking at. But think of the universe of reference it embodies: the hands and the sweat of the person responsible for cutting the wood, which was once a mighty tree, full of energy, in the middle of a dense forest, high up in the mountains; the loving work involved in crafting its form; the joy of the purchaser on buying it; the many moments of weariness it has alleviated; the sorrows and the joys of those who have sat upon it, in a grand reception room or, perhaps, in a pokey little dining room in the suburbs… All, absolutely all, of these aspects have their importance.”

And, the list could easily have gone on for pages. Indeed, it could have gone on for ever, for there are no limits to the associations and connotations that can emanate from no matter what object or word.

Games of children

Tapies goes on to liken the intellectual activity which he is proposing to the games of children, which he claims are used by them as “tools for growing up”. He exhorts us to play our own creative self-educational and life-maturing games when we look at paintings. He also warns us that when we do so, we should never get bogged down by our ideas of what paintings should be, for “a painting can be anything whatsoever.” Finally, he sums up by inviting us to combine the three activities of “play”, “attentive looking” and “active thought”.

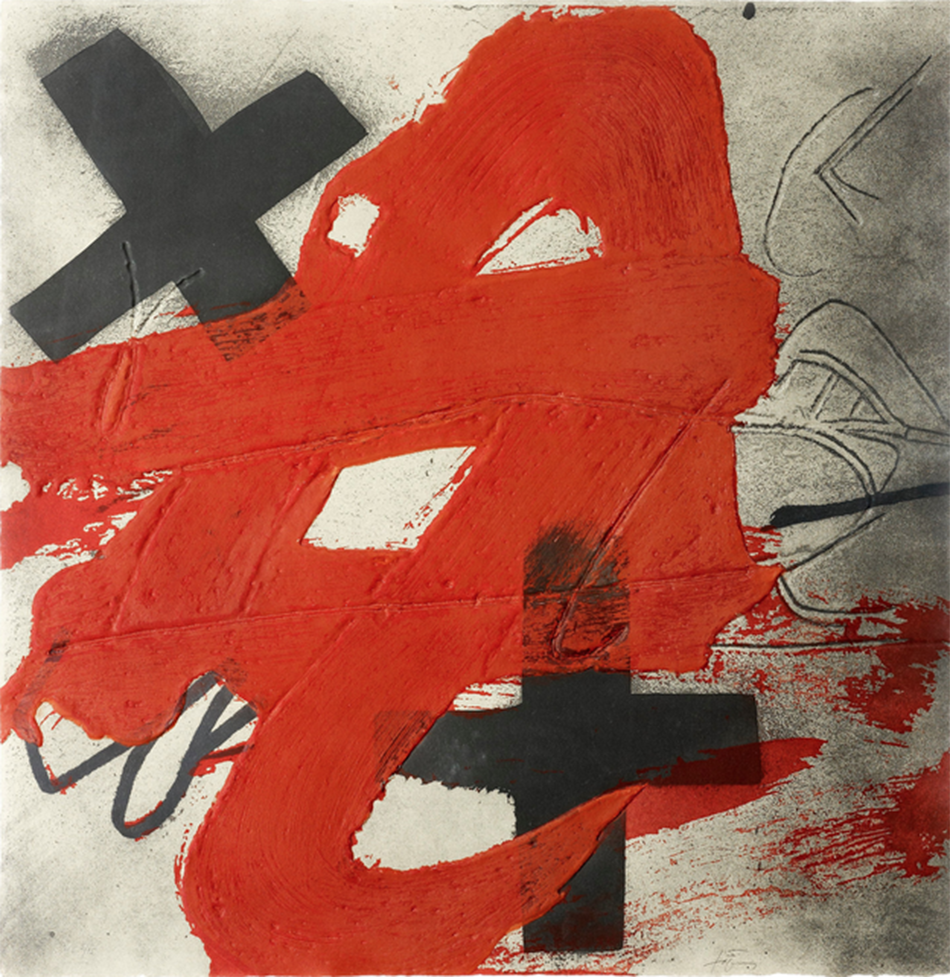

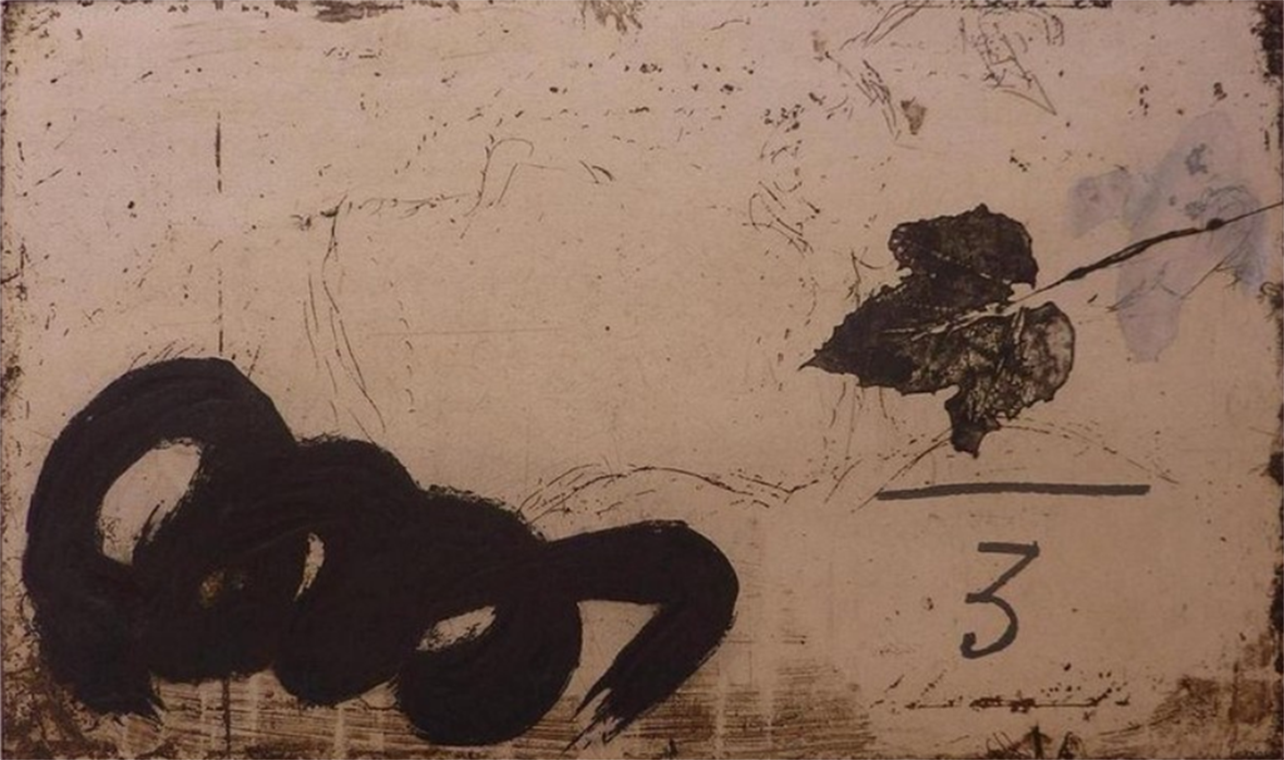

.

.

.

Why the chair?

Tapies does not explain why he chose a chair for his illustration, but it may be that, somewhere in the back (or, possibly, front) of his mind, he was thinking of Van Gogh’s famous painting of a chair in which, by general agreement, the Dutch artist so admirably succeeded in transforming a humble object of daily life into a universal symbol of human experience.

He certainly cannot have been thinking of the white-painted dining room chair in my Painting School, which I have so often used for drawing lessons designed to introduce my students to a more penetrating awareness of abstract relations and a more vital appreciation of the dynamic possibilities of linear juxtapositions, rhythms and arabesques. Nor is this an aspect of visual exploration mentioned in his short polemic even though the analytic-looking involved can point the finger towards another whole world of new experience.

As well as Tapies, John Constable (who claimed that “it does not matter how ugly an object is, when light falls on its surface, it becomes beautiful”) and Marcel Duchamp (who challenged us to consider both a urinal and hat rack as art objects) have helped us to understand, such potential lurks in even the most seemingly unremarkable or said-to-be ugly objects that we come across in the course of everyday life. Moreover to arabesques and linear rhythms and the play of light can be added, whole-field lightness and colour relations, local interactions between colours and between the astonishing variety of textures that enrich our visual worlds. Each quality of appearance, whether on its own or in combination, provides a wonderland for visual exploration.

Taking the idea further

Or, taking a different tack, it would be easy to focus-down on the different parts of the chair, such as the shapely lathe-turned legs, the finely plaited seat or the machine-sculpted back-support. All are objects in their own right, capable of being treated to creative game-playing looking strategies such as those advocated by Tapies, those I suggest as a teacher and, indeed, a potential infinity of others lines of inquiry.

And, it hardly needs saying, the same is also true of the parts of all other objects (for example, the trunk, the branches and the foliage of trees), for the parts of those parts (for example, the bark, the twigs and the leaves) and for the parts of the parts of the parts (for example, the lichen, the buds and the skeleton of veins), etc.. And all this without taking context into account or using mechanical means (for example, microscopes, infrared cameras or computer software) to transform our vision.

Context

With respect to context, it is well known that the meaning of an object can be transformed by placing it in a different settings. If Van Gogh’s humble chair were to be placed in the reception room hall of a grand palace or a jewel-studded golden throne were to be transported to the grimy kitchen in a run-down slum dwelling, how differently each would be viewed. If a red screen were to be set up in front of a green wall, its colour would stand out forcibly. And if the wall had been painted the same red as the screen, it could be almost camouflaged.

Mechanical aids

As for mechanical aids capable of transforming vision, a panoply of ones used by artists over the centuries were listed in Chapter 2 of “Drawing on Both Sides of the Brain”. And others can be found in later chapters. Almost all these not only help us to focus-down onto parts or aspects but also provide new contexts capable, with the help of comparisons, of directing attention into unaccustomed channels of experience.

Nor is it only artists who have resorted to perception-transforming devices to extend or sharpen their awareness. Surely, their use must be routine in all spheres of creative looking. Certainly, as indicated above, scientists have made abundant use of them to delve deeper into the objects and subjects of their interest. Indeed, they have done so such an extent that it has became impossible to imagine how most branches of science could progress without them.

But how many artists or scientists have subjected their findings to the games playing approach advocated by Tapies?

Other Posts from “Having Fun with Creativity”, Chapter 10 of “Fresh Perspectives on Creativity”

- Playful fancies as a stimulus to creativity

- An inspirational story: a child draws a potato

- The case for being a flat-earther:

- The nature of truth

- Tapies advocates playing games

- Cézanne fall short

Other Posts from “Fresh Insights into Creativity”

Click here for list of Posts in all the other categories

d’accord . Le jeu est la manière de conserver la capacité à s’enthousiasmer. L’enfant est capable d’enthousiasme de nombreuses fois dans une journée,cette capacité est plus faible chez les adultes. Avec enthousiasme tout peut s’accomplir! Merci Francis de ce “post”.

I love this post, Francis! So true, we need to play more in order to broaden our view of the world and to sharpen our creativity.

Another thought provoking piece. The ideas of attentive looking and active thought have resonances beyond painting: we have just placed a romanesco cauliflower on our table with its intricate growth patterns in fractal design – an object for contemplation before eating.