The drawing lesson that can be found in Chapter 10 of “Drawing with Feeling“, is the most important chapter in my book on the practice of drawing. All the other chapters either lead up to it or hinge upon it.

The key difference between the method described in this book is that it concentrates on training our capacity for getting a feeling for relativities of length, angle and position of lines drawn on the page. The method was developed on the basis of my research findings, when I was a Senior Research Fellow in the Department of Psychology at the University of Stirling in Scotland. I was later to discover that, despite many superficial differences, my drawing lesson also has much in common with the core ideas of Horace Lecoq de Boisbaudran, the highly influential 19th century teacher. The big difference between his method and mine is that while he emphasises training the memory in a general sort of way, mine, with the advantage of knowing about important 20th century advances, emphasises the aspect of memory that deals with training the “feeling system“.

The drawing lesson in this chapter is a description of the one that I give to individual students. It usually takes about three hours of highly concentrated trial, error and in-depth explanation of why the error has been made. After it, almost everybody, no matter their original level of attainment, will find that they have taken a significant leap forward in their ability to draw from observation with accuracy. The leap forward for beginners is regularly spectacular and many, already skilful, professional artists have been impressed by the improvements in both the speed, accuracy and expressiveness achieved in their drawings from observation. Some idea of their appreciation can be obtained from the “exhibiting artists” section of the student comments page. In the next chapter it will be shown how students can build on what they have learnt and, as a result, make signifiant progress, both in drawings made from memory and in line-production speed.

While the drawing lesson and its follow-ups enable students to surprise themselves (and sometimes me as well) with the progress they make in one day, they will need to follow up with the exercises suggested in the next chapter and in various other places in this book. If they do so regularly, over a period of time, they will find themselves experiencing, over and over again, the advantages of a method that is centred upon the use of comparative looking, used as a tool for expanding awareness, and of the “sensing” of relativities, as a means of guiding line output. The reward will be an ability to create drawings, whether made quickly or slowly, that are enhanced by their new found and personalised, feeling-centred, information pick-up skills.

Converting a live drawing lesson into the written word has inevitable disadvantages, particularly when it is one that requires up to three hours of sustained concentration from both student and teacher. For this reason, however clear my explanations, Chapter 10 was never going to be an easy read. A consequence of this is that getting the most out of it may prove to be hard work. If it does, I hope that you will not let this put you off, for taking as much time as is necessary to understand and implement each and every step will be well worth the effort.

The centrality of feeling

The big differences between the method explained in this chapter and other methods are the emphases on:

- Using accuracy as a way of extending awareness, rather than as an objective in itself.

- Enabling liberation from widely taught methods that distance us from our feelings.

- Sensing as a way of measuring spatial relativities (of size, length, orientation and position on the page).

- Coordinating the information pick-up system with the organisation-of-action skills system to enable fast, information-rich results.

- Opening up opportunities for “personal expression”, through exaggeration (Van Gogh, et al.), distortion (Toulouse-Lautrec, et al.) and feeling-connected mark-making (Bonnard, et al.)”.

Before attempting to follow the instructions in Chapter 10, it might be well worth revisiting Chapter 4 “The sketch and the feel system“. There, beside elaborating upon what I mean by the “feel-system“, I suggest a number of simple exercises to give you experience of using it.

CHAPTER 10 – THE DRAWING LESSON

Below you will find some images and, below them, some links to already published chapters from BOOK 1, “Drawing with Feeling” and from BOOK 2, “Drawing with Knowledge” , both from the two-book Volume that I have written on the practice of drawing: “Drawing on Both Sides of the Brain“.

Six rapidly drawn images in ink and pencil

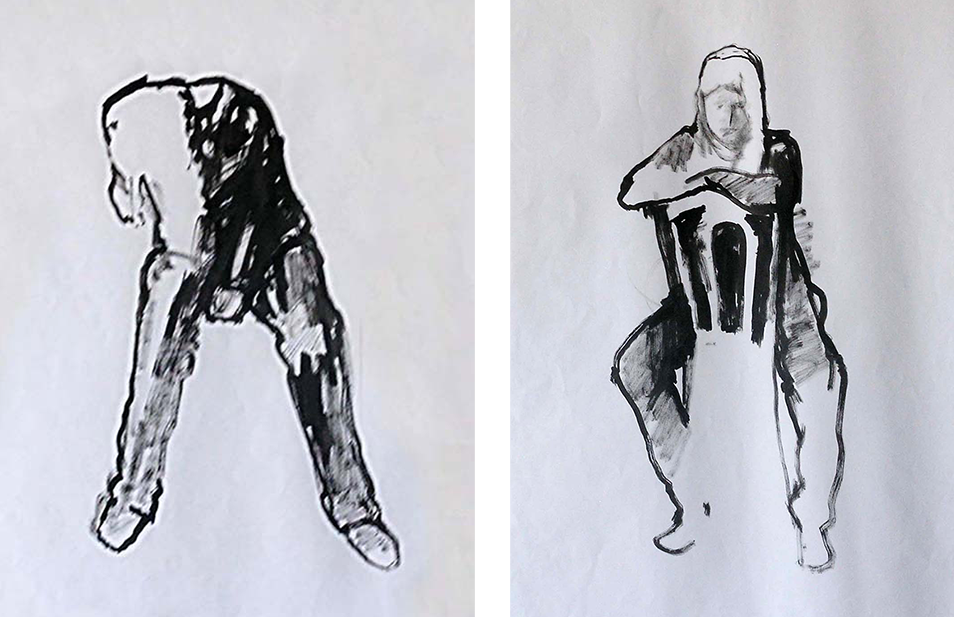

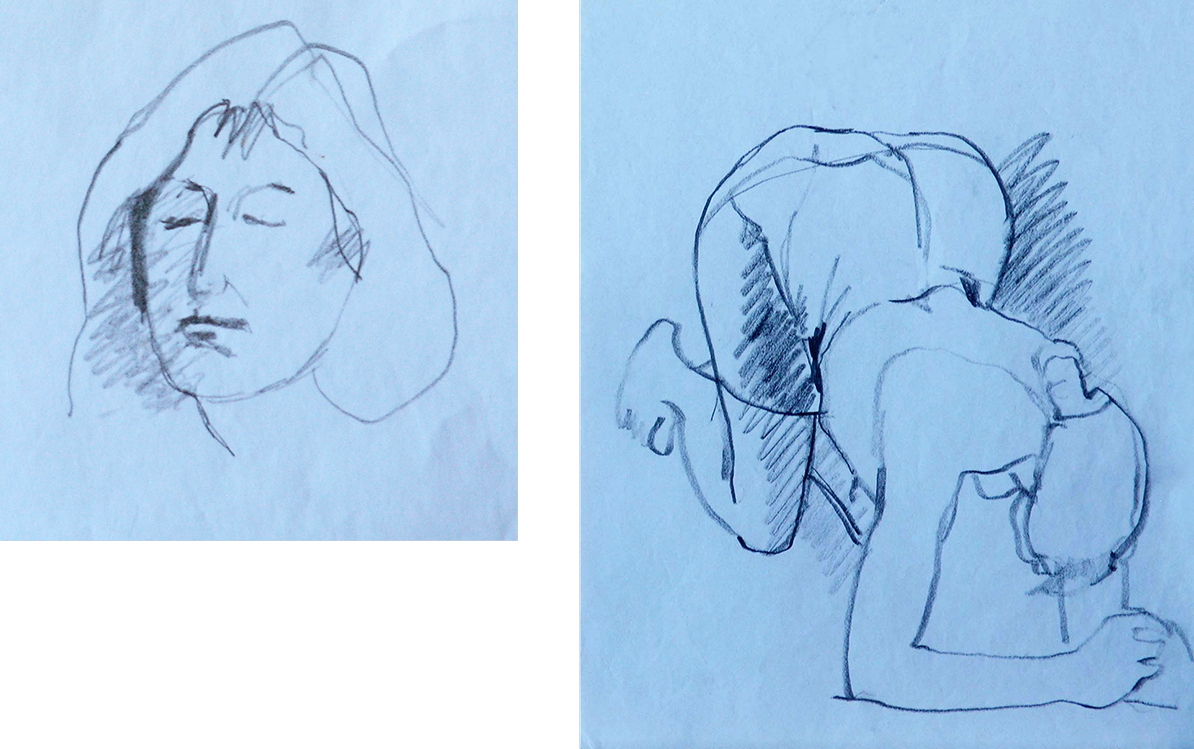

Illustrating how feeling-centred, personal responses to a pose can be conveyed in the rapidly made drawings

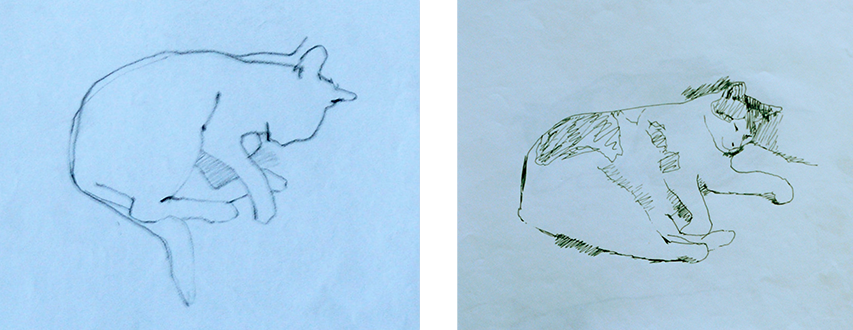

Cats doing what they do best: Creating eye-catching patterns of curvatures, and softening hearts, while lazing around

Catching the energy of unplanned body positions that cannot be trusted to last more than a few seconds

How simple lines can catch a fleeting expression or a chance pose that unexpectedly catches the eye

![]()

INTRODUCTORY

VOLUME ONE : “DRAWING ON BOTH SIDES OF THE BRAIN”

BOOK 1 : “DRAWING WITH FEELING”

The chapters so far loaded:

- Introduction to BOOK 1 : “Drawing with Feeling”

- Chapter 1: Accuracy versus expression

- Chapter 2: Traditional artistic practices

- Chapter 3: Modernist ideas that fed into new teaching methods

- Chapter 4: the sketch and explaining the feel-system

- Chapter 5: Negative spaces

- Chapter 6: Contour drawing

- Chapter 7: Copying Photographs

- Chapter 8: Movement, speed & memory

- Chapter 9: The drawing lesson – preparation

BOOK 2 : “DRAWING WITH KNOWLEDGE”

The chapters so far loaded:

- Chapter 13 : Introduction to “Drawing with Knowledge”

- Chapter 14 : Linear Perspective

- Chapter 15 : Some core ideas

- Chapter 16 : Eye-line problems

- Chapter 17 : Head movement opportunities

- Chapter 18 : Axes of symmetry

- Chapter 19: Anatomy reviewed

- Chapter 20 : Structural basics

- Chapter 21 : Deformations – muscles, fat, clothes

Go to top of page

Go to list of all other contents

i

Thanks for posting this chapter. You have combined diverse fields of knowledge, your own art practise and years of teaching experience to devise a highly effective drawing system. One that is grounded in the complexities of how the eye-brain functions. That is proved by the quality of much of the drawing done at the School. And it makes sense in terms of the other chapters. So it’s very valuable, and it reminds me to go back and revisit this method.

You have recognised that the chapter isn’t an easy read- it’s well written just that it takes a lot of words to describe looking and making a mark. Would filming a session work? Perhaps even with a spit screen showing the paper and the subject, zooming in on the mark making. Any, You Tubers reading?! Of course the viewer would never see exactly the same way as the student drawing but perhaps it might open up this method to a wider audience.