Today, I have been editing the entry for aerial perspective in the Glossary for my books. As I was making my corrections, I had the idea that readers of the Posts Page of this website might like a preview of this and future Glossary edits that I feel might interest them. So, to start the ball rolling, here is a slightly expanded version of the one on aerial perspective, with four images added.

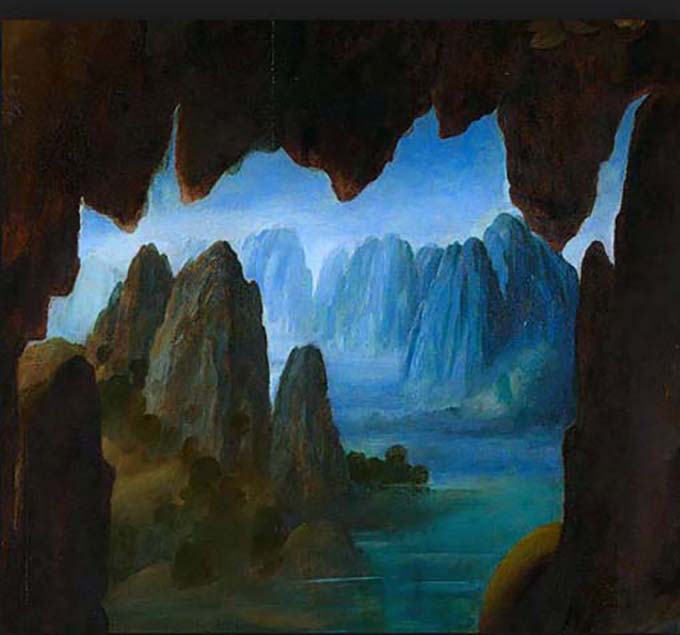

Aerial perspective: Between any viewer and the surfaces of the objects at which they are looking lies a portion of the earth’s atmosphere. In addition to the transparent gases that make up air, this contains quantities of dust and other particulate matter (such as the water droplets in mist and, more evidently nowadays, various kinds of pollution). The effect of the intervening atmosphere on the appearance of distant hills and objects seen is well known to us all. We all perceive distant parts of landscapes being bluer and/or greyer and lighter than nearer parts, and objects seen through mist or fog appear progressively greyer and lighter as the distance between them and us increases. Many artists dating back to the Italian Renaissance, most famously Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) and Claude Lorrain (1600 – 1682), have demonstrated the value of applying these principles in paintings. So convincing was their effect, that they were adopted as “rules” by the French Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture soon after it was founded in the mid seventeenth century. No one would dispute that the images in Figure 1 and Figure 2 produce a sense of progressive distance.

.

.

.

Warnings

- Although the theory explaining aerial perspective is scientifically sound and although it virtually always has an important effect on how we perceive both distant parts of landscapes and objects on misty days, it has no discernible effect on how we perceive objects within an arms length. So at what distance does its influence become apparent? The answer is that it varies according to the composition and density of the particles floating about within it. Thus, on dry, bright days of the kind that often follow abundant heavy rain, when the air has been washed clean, the visibility of atmospheric intervention is minimised, whereas on a hot sultry or misty days, when the air is at its fullest of dust and pollution, it is maximised. In practice, this can mean that on a clear day its effect on the appearance of objects hundreds of meters away may not be discernible.

- Despite these facts of appearances, over the years, I have found that many students, when they first come to my Painting School, have been in the habit of adding blue to objects much nearer than that (in one exceptional case, a newcomer, when painting a bunch of flowers in a vase, added blue to the colour of flowers and foliage at the back of the arrangement, arguing that it made it look further away). When I see this being done, it tells me is that the student in question cannot have been looking at the near/far colour/lightness relativities. If so, how can they appreciate the amazing riches of colour relations in nature? They need to learn that rules are not for following blindly, but for testing, a process which will always open doors of awareness.

- To further complicate the situation, there are a number of other variables that can result in people perceiving more distant surfaces of a particular colour as brighter and more fully saturated than nearer surfaces of the same colour: In other words, the opposite of the aerial perspective rule. For example, in summertime, the green canopies of distant oak trees that are illuminated by bright sunlight will look lighter and brighter than those of nearer oak trees should they happen to be situated in the shadow of clouds. Also, a boat on a lake that is painted with a fully saturated red that is actually further away from the viewer than a boat painted with a desaturated red will still look further away. If we made a painting of them, matching as best as possible the colours as we see them, the laws of aerial perspective would predict that the further boats would be perceived as being nearer than the nearer boat. Clearly there needs to be a way of depicting distance that has nothing to do with the representation of atmospheric intervention. Luckily there are several of these, including overlap, relative size and texture cues, but only one of them necessitates the use of colour. Unfortunately, this colour-dependent way of enhancing illusory pictorial space appears to be little known, despite its solid foundations in well known history, its sound scientific underpinning and the ease of its practical application. Much of my book “Painting with Light and Colour” is devoted to giving it new life. If you want to know more, read chapters already published on this website and watch for later Posts.

Two examples of minimal effect of aerial perspective, containing contradictions to the laws as exemplified by Clause Lorrain.

John Constable (1776 – 1837) was a great admirer of Claude Lorrain, but he looked more carefully at nature. Figure 3 and Figure 4 are images of two of his paintings that contain elements that are not consistent with a rigorous interpretation of the laws of aerial perspective. See how many you can find?

.

.

.

Now look at paintings by the Impressionists – Monet, Renoir Pissaro, Cezanne, Gauguin, Bonnard, etc. – to see how much they make use of the rules of aerial perspective. Where they do make use of them, was this the result of applying the rules or of looking carefully at nature? According to what is written above, far distant hills should always actually look bluer or greyer, but what about landscapes representing the kind of distances depicted by Constable or shorter ones?

Effect of patchy cloud cover on relative brightnessess

Finally to ram the point home, here are three photographs that illustrate how patchy cloud cover can produce contradictions to the laws of aerial perspective.

.

.

Figure 5 illustrates an exception to the law. Due to their being brightly illuminated by sunlight, the walls of the distant church tower are much brighter than those of the house in the foreground, which is in the shadow of passing clouds.

.

.

In Figure 6 the situation is reversed. The walls of the house in the foreground are now brightly illuminated by direct sunlight and are much brighter than those of the church tower, which is now in the shadow of passing clouds.

Figure 7 shows:

- The far house,

- The strip of green field in front of it,

- The sunlit patches of brown earth in the ploughed field,

as being brighter than,

- The near house,

- The ribbon of green field in the bottom left of the image,

- The area of brown earth immediately above it.

.

.

In all three images atmospheric intervention is playing a part, but in Figure 5 and Figure 7, its effects are being obscured in the ways described.

.