“Painting with light”:

The main purpose of this Post is to explain what I mean by “Seurat’s new idea”. Most people would probably leap to the conclusion that I am referring to the “Pointillist method” that he developed, and for which he is justly renowned. But the method was never the main idea, which was to “paint with light” (as opposed to merely “painting light”). No previous artist had attempted to do this.

Artists that preceded the Impressionists, at least since the Italian Renaissance, had given priority to depicting effects of natural or artificial light on the appearance of objects and scenes in their paintings. They made impressive progress with this project by conceiving matters in terms of whole-field lightness relations (chiaroscuro). Seurat’s new idea opened up the previously unexplored possibility of introducing the dimension of colour into the mix. In doing so, whether directly or indirectly, Seurat was responsible for opening the way for the exploration of new worlds of colour related experience.

Part of the reason for this was simply the huge increase in the number of colours that Seurat’s method brought to the notice of his contemporaries. Of particular interest for the Impressionist and for all artists coming after Seurat shared his method was that, from now on, chiaroscuro was no longer the only way of imbuing paintings with a sense of light. A main reason for this was that the same levels of nuance that had previously been obtained by means of lightness variations alone could now be achieved by compressing colour variations into much narrower ranges of lightnesses: By the 1960s, art school students were being taught that anyone aspiring to be a colourist should confine themselves to using equal lightness colours.

The idea of compressing lightness space played an important role in the remarkable explosion of colourfulness that is characteristic of innumerable paintings produced after Seurat exhibited “La Grande Jatte” in 1886. This revolutionary development been set on its way by the discovery by scientists in the late eighteenth and earlyy nineteenth century that colour is not a property of surfaces in the external world, but a creation of eye/brain systems. In the wake of this mind blowing reality and the availability of an ever increasing range of pigment colours produced as spinoffs from the Industrial revolution, earlier Modernist artists were using brighter colours and juxtaposing complementary pairs before Seurat came on the scene. However, two requirements of the Pointillist method pushed matters significantly further. These were:

- The systematic use of juxtaposed complementary colour pairs, within the optically mixed arrays of tiny dots that characterise Pointillism.

- The need to conceive of colour-mixing in terms of a colour circle with many more segments than the six segment one (consisting of three primaries and their three complementaries) favoured by the Impressionists. Seurat’s idea meant that he had to represent as many parts of the visible spectrum as possible. To do this he needed to make use of the widest range of the most fully saturated pigment colours available.

The ramifications of all this revolutionised painting, including the new understandings relating to the depiction of:

- “Illusory pictorial space”

- “Surface” and “surfacelessness”.

In summary, these innovations not only hugely increased the range and subtlety of colours, colour combinations and colour interactions that could be achieved in paintings, but also provided the possibility of enhancing all light-related qualities in them.

For more details click on the link below to Chapter 8 of my book “Painting with Light and Colour”. For those who have not read the previous four chapters, the next section provides a short resume of them (links to the chapters themselves can be found at the bottom of this page).

Short resume of previous chapters

- Chapter 4 : Describes the Renaissance approach to painting light, which centred on local and whole-field lightness relations with particular reference to finding the darkest and lightest regions in the scene (chiaroscuro) and gradations of lightness across surfaces. In this scheme of things the depiction of shadows was a matter of painting “what you see”, which seemed reasonable enough, but brought with it all sorts of unsuspected problems.

- Chapter 5 : Focuses on the scientific revolution in the understanding of light and colour that had its origins in the work of Isaac Newton and the insights of the numerous scientists who realised that all sensory experiences including those that relate to colour and effects of light are made in the head. Newton clarified the physical nature of light. The perceptual scientists introduced concepts like the“three primaries”, “induced colour”, “complementary colours” and “colour/lightness contrast effects”.

- Chapter 6 : Shows that the Impressionists had an agenda which included the idea of emphasising the reality of the picture surface and playing off against one another the ephemeral and the permanent aspects of appearance.

- Chapter 7 : Uses photographs to elucidate the meaning of the words “opaque”, “translucent”, “glossy” and “matt”. Particular attention is given to effects on appearances of interreflections and viewing angles.

The diagrammatic origin of Seurat’s new idea

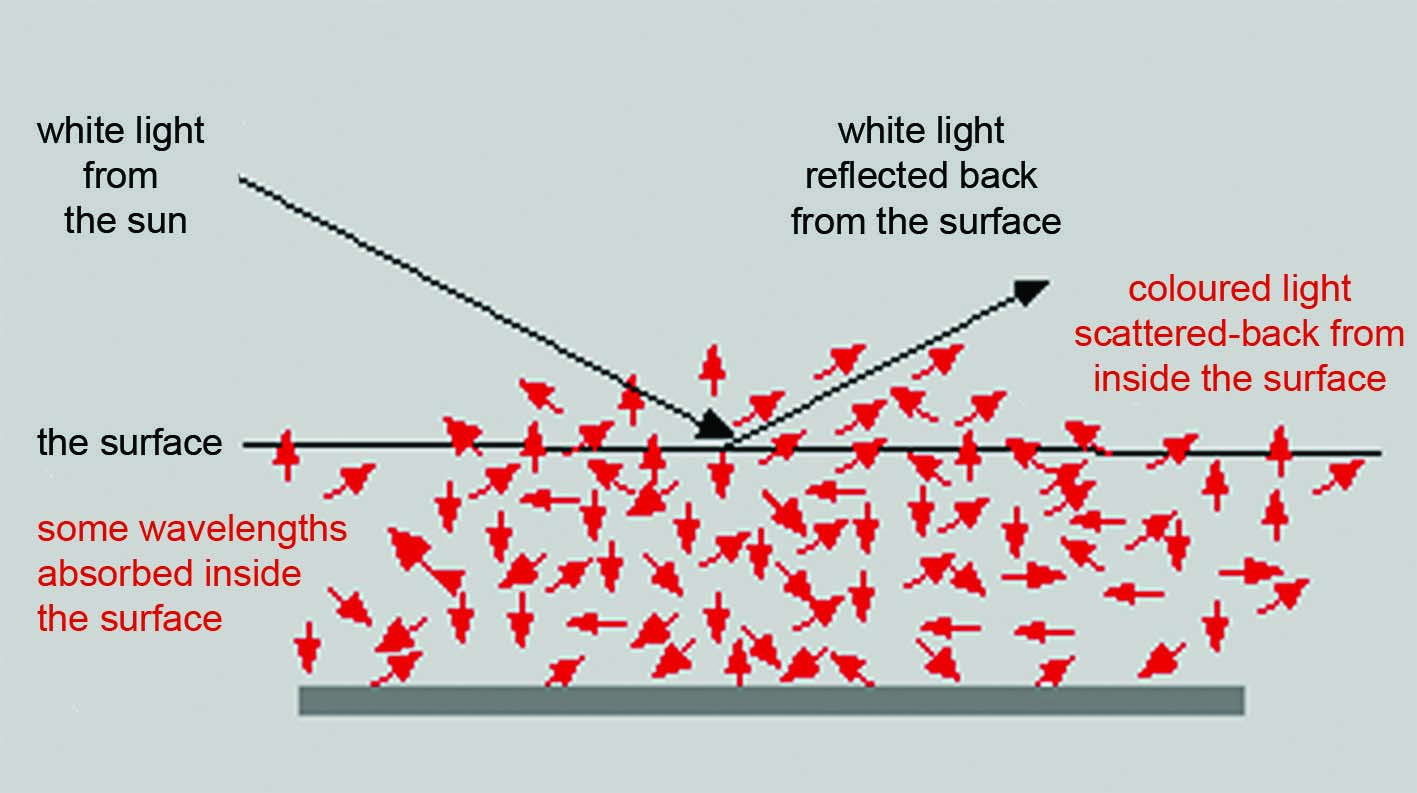

As it does not appear in Chapter 8, but earlier in the book, I am including in this Post the diagram from a physics book that kick started Seurat’s new idea. It was from this that he learnt that the white daylight light that strikes a surface interacts with it in one of two ways:

- One part enters the surface and is scattered around inside, before being scattered back out again. While inside, some wavelengths are absorbed. The remainder are scattered-back-out again to produce the limited wavelength combinations that give us “body colour”.

- The remainder never enters the surface, but is reflected back directly from it (as from a mirror), such that it leaves it without changing its wavelength composition to produce “reflected light”.

The component that interested Seurat is the “reflected light”. By combining his understanding of this with the discoveries of perceptual scientists mentioned above, Seurat believed that he could represent it in paintings by means of mosaics of tiny dots containing juxtapositions of complementary, or near-complementary, pairs.

.

CHAPTER 8-SEURAT AND PAINTING WITH LIGHT

.

The inspirational diagram

Posts relating to other chapters from “Painting with Light and Colour”:

- Introduction: the little known Science behind many of the original practical suggestions.

- Chapter 1 : The dogmas

- Chapter 2 : “doubts”.

- Chapter 3 : “The nature of painting”

- Chapter 4: Renaissance ideas

- Chapter 5 : New Science on offer

- Chapter 6 : “Early Modernist Painters”

- Chapter 7 : The Perception of surface.

- Chapter 8 – Seurat and painting with light

- Chapter 9 – Painting with light

magnifique. Revenir sans fin sur les connaissances des “mystères” de la couleur m’aide pour suivre mon chemin de créativité. Merci Francis

This is so important to understanding how and why each person quite probably sees things differently.

The intersection of art and the sciences is truly thrilling to uncover here, thank you for your writing!

Hello Sawyer, So good to hear from you and thanks for your positive comment. When I saw the diagram that inspired Seurat and realised how it related to his idea of “painting with light” as opposed to just “painting light” (which was an aim of mosts artists since the Italian Renaissance), it changed my life. It did so by setting me on the way to the cooperations with scientist colleagues at the University of Stirling that enabled me (a) to explain “colour constancy” , (b) to discover (as far as I know for the first time) visual systems that that tell us about surface solidity, surface form, in front/behind relations and ambient illumination, and (c) to find a reliable method of using colour to enhance the sense of illusory pictorial space.

so interesting !

Thought provoking

Thanks for your comment. You might be interested in reading my reply to Sawyer Smith above.

This is a pivotal post. It is key to understanding a large part of the basis of your research and the practical applications you later devised to help artists paint, though in a much simpler way, the very reflected light that Seurat sought to depict in a much more painstaking manner. It makes one eager to get out and paint! Thank you again for sharing this little known knowledge!

This is a terrific chapter. It is especially terrific being part of Francis Pratt’s Zoom Class discussion and this chapter’s further unfolding through the questions and answers provided by fellow painters. The additional information, provided by Francis as he responds to these questions and his further discussion is of great practical value to me.