Recently I was asked if I could post the five colour mixing chapters from my book “Painting with Light and Colour” (Chapters 11 – 15). I will be surprised if you do not find that many of the ideas in them are new, interesting and practical. At the bottom of the page is a link to Chapter Eleven, the first of the four chapters, whose title is, “Colour mixing – definitions and misconceptions”. To whet your appetite (below the image) I have included a slightly edited version of its “Introductory”.

Introductory to Chapter Eleven

Introductory

At the outset of my life as an artist, my conception of colour-mixing was of a dry and mechanical subject. I thought of it as no more than one of those necessary basic skills that could easily be picked up along the road. To my surprise, nothing turned out to be quite so routine as it had seemed, and one line of enquiry led to another in a most seductive way. Each new development plunged me deeper into the history either of science or of art, until an engagingly coherent story emerged. The result was a practical understanding of a kind that might be difficult to find elsewhere.

“Most how-to-do-it art books have sections on colour-mixing and there are a number of tomes that offer technical information for professionals. These latter tell us that scientists have understood the physics underpinning colour-mixing theory for a very long time: Certainly they have done so since James Clerk Maxwell’s lecture on colour vision, given at the Royal Institute, two years before the First Impressionist Exhibition in 1874.

In view of the availability of all these sources of information, it might be thought that there is nothing left to add. Unfortunately, this is far from the case. The problem is that:

- Too many painters are being seriously misled by the half-truths and even falsehoods which have entered into the stock in trade of popular colour-mixing theory.

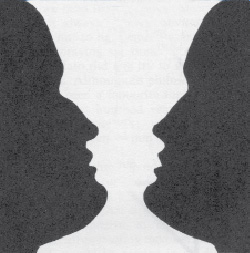

- Science has far from stood still since the 1870s. Particularly since the 1970s, scientists have been finding out a great deal of new information about how eyes and brains work and, as a result, have arrived at a number of new understandings that could help artists in practical ways, which are not being made use of by the artistic community.

For these reasons and others, it is clear to me that there is a need for the up-to-date approach to practical colour mixing that is supplied by the next chapters.

One approach to clarifying matters is to place the information presented in an historical context. Doing so reveals that:

- Some of the best of ideas have been obscured by the passage of time.

- The evolution of colour-mixing theory, owes much to parallel development of the histories of science and of art.

- The story of when, how and why artists adopted new colour-mixing practices, provides many insights into their potential uses in painting.

With respect to the links between the discoveries of the scientists of visual perception and the practice of the artists, the evidence is usually sparse and often ambiguous. To compound the problem history (not least the history of science) becomes distorted because it is told by people who write with the benefit of hindsight and sometimes from the perspective of a particular prejudice.

It may surprise some people to find how many famous scientists are credited both with more originality and much more fully developed and rounded versions of their ideas than they actually had. A mismatch of this kind may be suspected in the relation between the confusions inherent in the early development of the ideas developed by Seurat and Cézanne and the neat synthesis of them by Professor Bohusz-Szyszko. Similarly it is unlikely that any of the early Impressionists had as clear a conceptual framework concerning the real surface/illusory space dynamic as was eventually to evolve from their pioneering ideas. While these are very interesting areas for discussion, the process of trying to unearth and pin down exactly what the early pioneers had in mind is a work for scholars. The focus of this book is artistic practice and it is the more refined picture as developed by the more recent artists and theorists that are the most useful in terms of their practical value.

We start a short survey of these by providing some basic definitions as used in this book:

.

CHAPTER 11 – COLOUR-MIXING-DEFINITIONS & MISCONCEPTIONS

.

Other Chapters from “Painting with Light and Colour”.

- Introduction: the little known Science behind many of the original practical suggestions.

- Chapter 1 : The dogmas

- Chapter 2 : Doubts

- Chapter 3 : The nature of painting

- Chapter 4: Renaissance ideas

- Chapter 5 : New Science on offer

- Chapter 6 : Early Modernist Painters

- Chapter 7 : The perception of surface

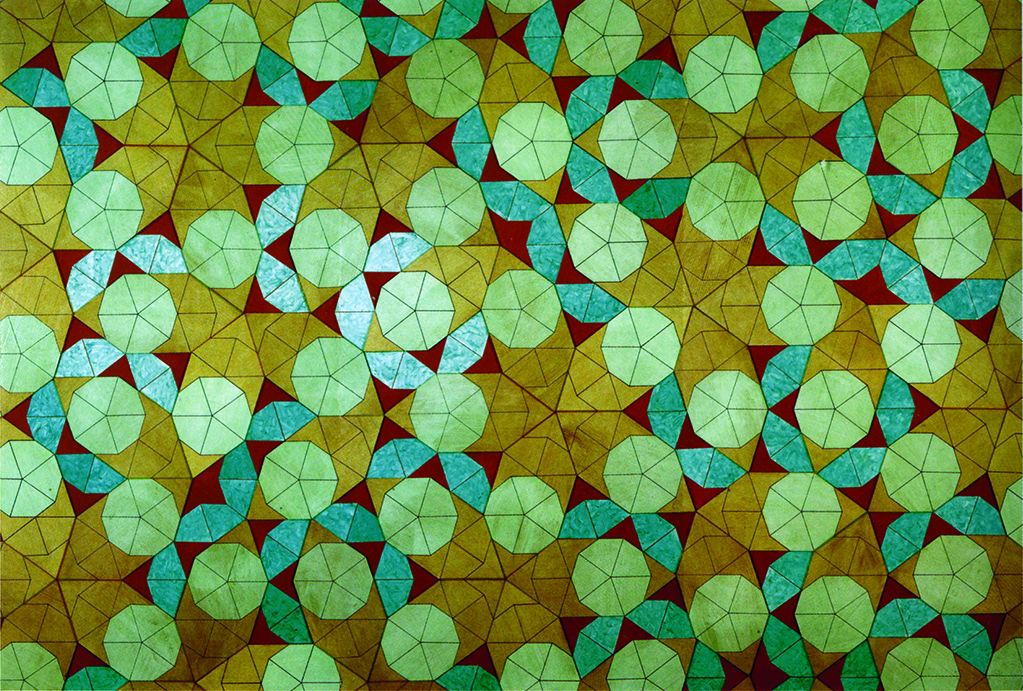

- Chapter 8 : Seurat and Painting with Light

- Chapter 9 : Seeing Light

- Chapter 10 : Illusory pictorial space and light

- Chapter 11 : Colour mixing – definitions and misconceptions

- Chapter 12: The colour circle: Misunderstandings

- Chapter 13 : Finding a maximum of colours

- Chapter 14 – Colour mixing made easy

- Chapter 15 – Colour mixing by layering

Other Posts on colour and light in painting:

- What are colourists? (1): Some of the many meanings of the word

- What are colourists? (2): Difference between meaning of the word for Venetian Colourists and for Modernist Colourists?

- What does the word “colour” mean?

Chapters from “What Scientists can Learn from Artists”

These deal in greater depth with subjects that feature in the other volumes